The usual Evening-Dress is so imperiously insisted upon, that it might be almost classed in the category of uniforms.

The American Gentleman’s Guide to Politeness and Fashion (1857)

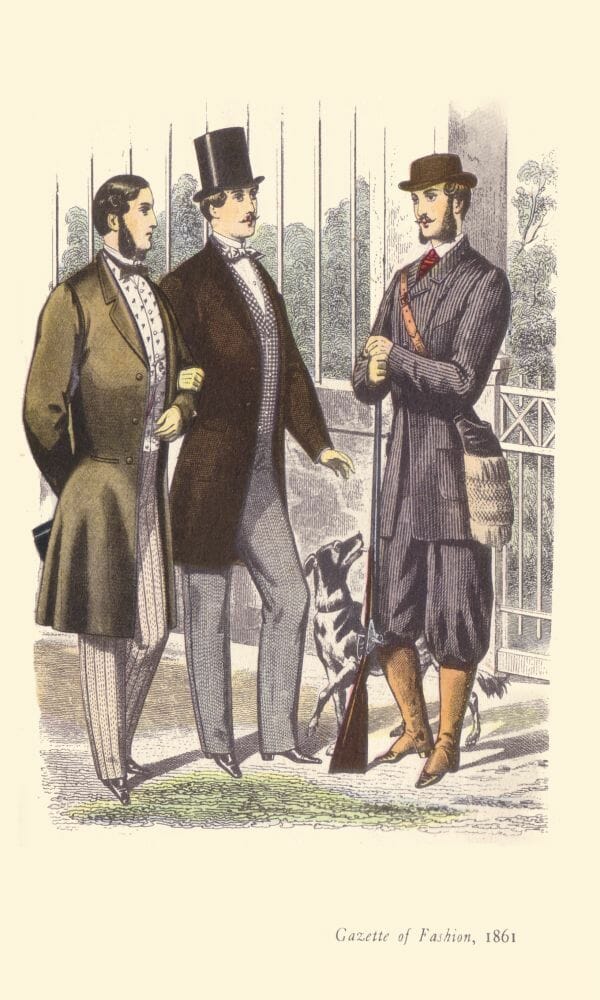

The New Look for Men: Somber Style

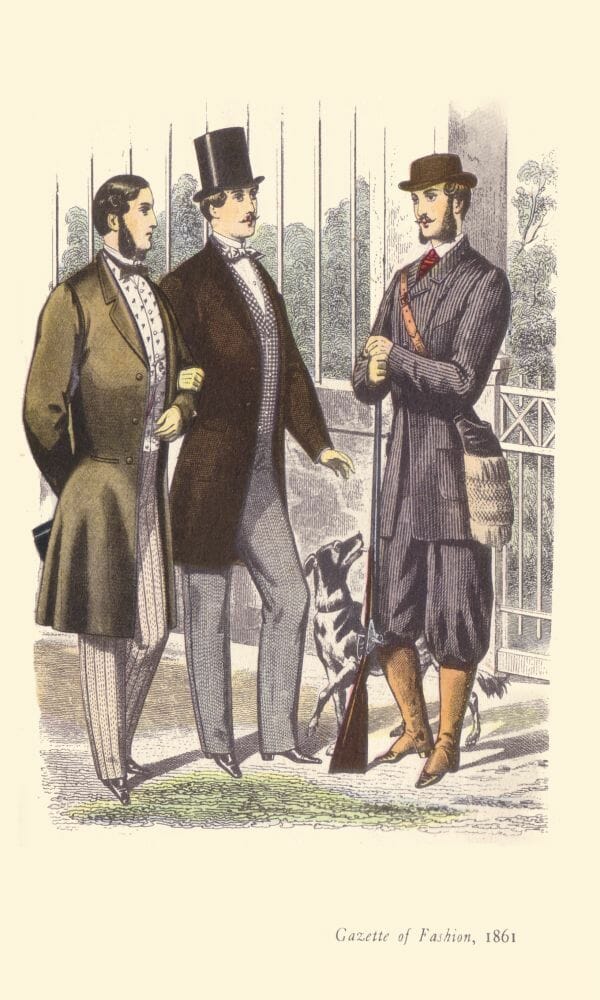

When Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837 the industrial revolution was in full swing. The prosperous emerging middle class strove for respectability and homogeneity and was heavily influenced by the solemn Protestant movement of the time. As a result, the impractical dandyism of the Regency leisure class was replaced by functional and somber sartorialism preferred by the men who, in the words of one historian “wanted to appear as grave and serious as the banks and factories they owned”. So it was that the concept of the gentleman trumped the idea of the courtier, leading The Tailor and Cutter to declare in 1878 that “dress in our day has ceased to be the index of a man’s social position.”

- The New Look for Men: Somber Style

- Victorian Evening Etiquette

- Differentiating Day & Evening Wear

- The Components of Victorian After-Dark Attire

- Changes in Coats

- Wonderful Waistcoats of the Early Victorians

- Pantaloons and Trousers

- Shirt & Collar: Ruffles Give Way to Pleats

- Neckwear: From Cravats to Bow Ties

- Early Victorian Footwear

- A Plethora of Hats

- Early Victorian Gloves & Outerwear

- Ready for Relief: Contemporary Critics of Victorian Formal Dress

- Dress Decorum & Formal Facts

Victorian Evening Etiquette

The Regency’s general sartorial hierarchy of Dress and Undress carried through into the Victorian era. One popular etiquette guide of the period summarized that “to be ‘undressed’ is to be dressed for work and ordinary occupations” while to be “dressed” was to show respect for society by wearing the garments “which the said society pronounces as suitable to particular occasions.”

Differentiating Day & Evening Wear

New to the era was a more distinct division of the Dress category into morning dress and evening dress. Morning dress was formal daytime attire. Evening dress – often referred to as full dress – remained the pinnacle of patrician apparel and the practice of dressing for dinner was essential for men who aspired to genteelness. Instructed Routledge’s Manual of Etiquette:

In the evening, though only in the bosom of your own family, wear only black, and be as scrupulous to put on a dress coat as if you expected visitors. If you have sons, bring them up to do the same. It is the observance of these minor trifles in domestic etiquette which marks the true gentleman.

Thanks to Britain’s global influence, this sartorial practice was adopted around the world. America’s Brahmins, who were the elite of the times, were eager to incorporate the refined traditions of their former rulers so as to imbue their young country with an Old Word civility. Said the highly popular American etiquette book, Sensible Etiquette of the Best Society:

The true evening costume, accepted as such throughout the world, has at length, though not without some tribulations, established itself firmly in this country. With advancing culture, we have grown more cosmopolitan, and the cosmopolitan evening dress, acknowledged everywhere from Indus to the pole, has been granted undisputed sway.

The fundamental etiquette of this new costume remained elusive to Americans, however. To the author’s dismay, most of her countrymen did not understand that evening wear was meant to be worn in the evening and instead considered it appropriate for any formal occasion, day or night.

The book also contained two notable exceptions to the universal custom of dressing up after dark:

- Sunday evenings were not appropriate for the finery of evening dress and so morning dress was worn instead.

- In some circles evening dress was considered to be an affectation, therefore “it is well in provincial towns to do as others do”.

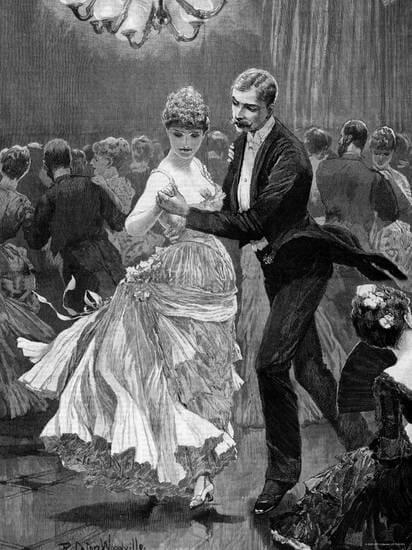

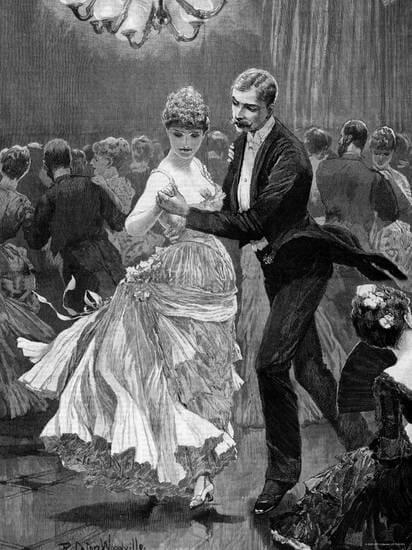

Theoretically, the new full dress maintained the old sub-hierarchy of relatively informal dinner dress, general evening dress, and most formal ballroom and opera dress. However, the distinctions between the strata were increasingly minimized as a result of the new era’s emphasis on uniformity and practicality. “Evening dress is the same, whatever the nature of the evening’s entertainment,” said Sensible Etiquette. “The theory is, that a gentleman dresses for dinner, and is then prepared alike for calls, opera, or ball.”

The Components of Victorian After-Dark Attire

Defining Victorian Evening Dress

Because the era spans over sixty years, there is no such thing as typical Victorian men’s evening dress. Instead, there are three fairly distinct phases:

- the early period from about 1840 to 1860 is notable for the gradual disappearance of Regency flamboyance

- the middle period from about 1860 to 1880 – also known as the beginning of the American Gilded Age – is notable for a strict codification of standards

- ]the late period from about 1880 to 1900 – the second half of the Gilded Age – is notable for the introduction of the dinner jacket and the consequent two-tier evening dress code

The following review covers the evolution of individual garments over the first four decades of the era as the dress code was gradually streamlined. The trends described here apply to both Britain and America unless otherwise noted.

General

As the evening outfit became more understated and uniform, the need to execute it well became critical. Superb materials, expert tailoring, and the latest styling were now the only traits that could distinguish the attire of a true Victorian gentleman.

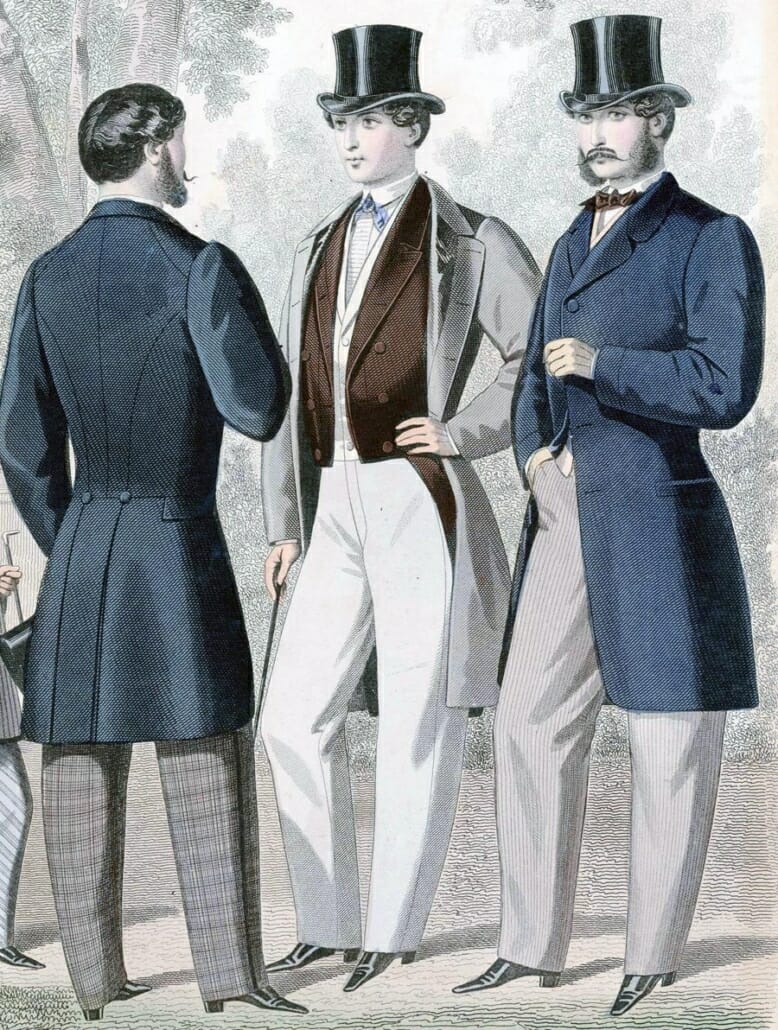

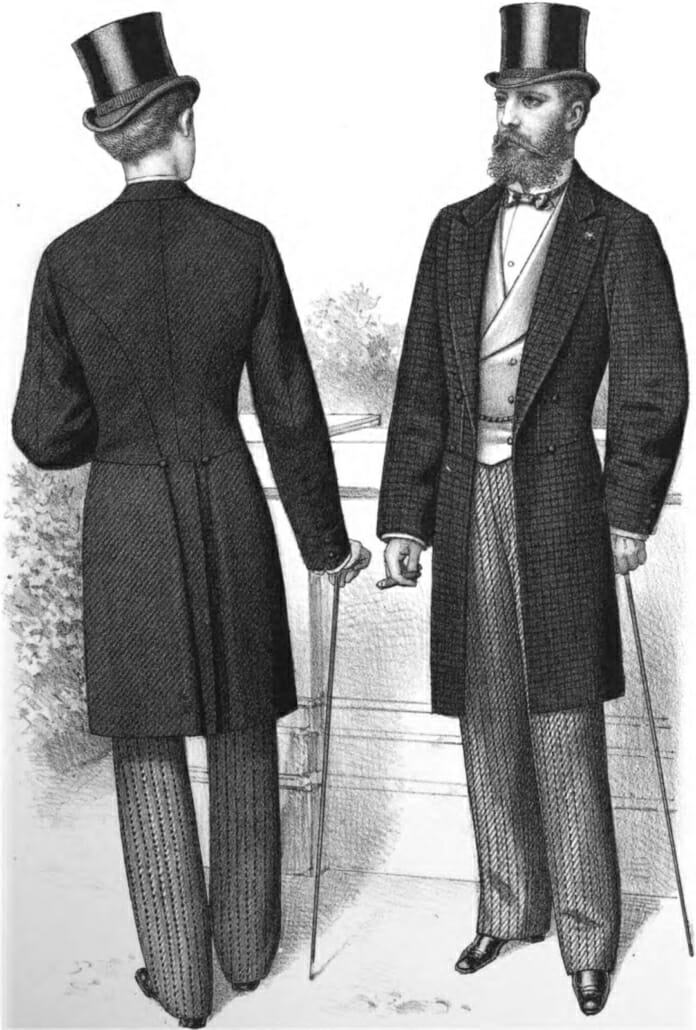

Changes in Coats

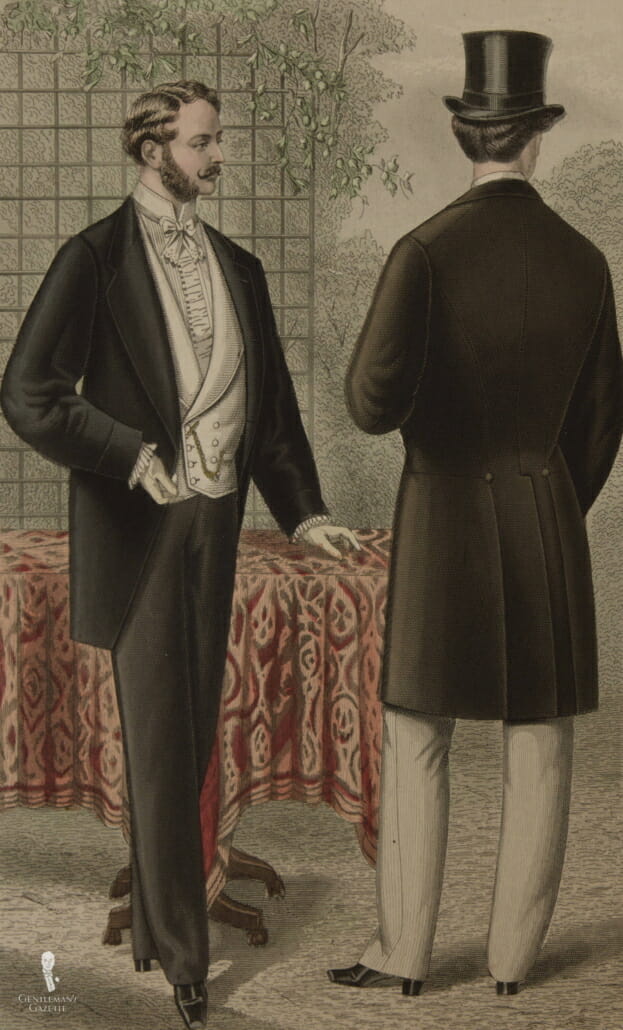

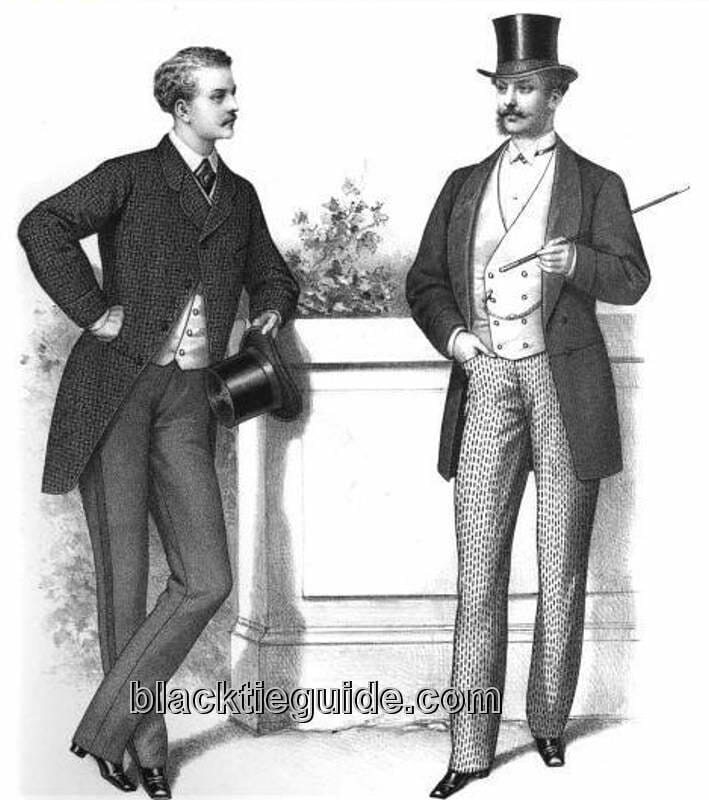

Initially the tailcoat – known as a dress coat during this time – continued to be used for both evening dress and morning dress. By the 1860s, it was worn only in the evening.

As in the Regency era, various dark colors were acceptable at first. The popularity of the blue version with gilt buttons and of the brown version waned over time until by 1853 “the proportion of black evening dress coats is twenty to one against any other color” according to The Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion. This increasing appeal of black during the Victorian era was due to a number of reasons: the previously mentioned somber Protestantism of the time, the pragmatism of living among the soot-covered cities of the industrial revolution and a decreed year of mourning following the death of the Queen’s husband in 1861.

Vanity also played a role in men’s preference for black according to The American Gentleman’s Guide to Politeness and Fashion which noted that it had a slimming effect and was a challenging look to pull off. “It is a very high compliment to any man to tell him that black becomes him, and it is probably owing to this property that black is chosen, par excellence, for evening or ball dress.”

Dress coats at first continued to be single or double-breasted and while morning dress coats were now designed to button up, evening versions were still intended to be worn open so as to show off the waistcoat and shirt front. This rendered the double-breasted’s buttons purely ornamental and by 1870s the most common style of evening dress coat had two buttons on either side of the front.

The V and M notch collars continued to be popular in the early Victorian era but the latter faded into history around the 1870s. Silk lapel facings appeared in the 1860s, which menswear author Nicholas Antongiavanni credits to the envy of civilian men wearing their tailcoats in the company of heraldic finery or full-dress military uniform. Unlike today, the facing did not cover the entire lapel but stopped at the edge of the multiple buttonholes that were standard on lapels of the time.

A stylish alternative in the 1860s was the roll collar (shawl collar) but it fell out of favor by the early ’70s. Velvet collars remained another fashionable option until the late Victorian period.

Dress coat sleeves often had false cuffs which were sometimes velvet to match the collar. Button trim began to appear in the 1870s. Pockets remained hidden in the tails because “in company,” said The Handbook of the Man of Fashion, “as little as possible should be borne in pockets of the coat.”

The length of the tails and the height of the waist continued to vary according to the whims of fashion.

Wonderful Waistcoats of the Early Victorians

The waistcoat was the last evening garment to retain its Regency flamboyance. At first, it was made of lavish materials such as silk, satin, velvet and cashmere and was often decorated with embroidery. By the 1860s, it was generally cloth or silk and limited to black or white. This choice of waistcoat color was one of only two variations allowed in Victorian evening dress (the necktie color being the other) although British etiquette authorities advised that white was unfashionable and should be limited to only the most formal of occasions.

Whether ebony or ivory, evening waistcoats were always single-breasted. They were increasingly low cut with a V-shaped opening until the 1870s when the U shape appeared. Conversely, the waist became increasingly higher so that by the 1850s the bottom was usually cut straight.

The shawl collar was typical on the waistcoat and two pockets were featured by mid-century. Buttons were either material covered or gilt or fancy stones. A trouser loop was introduced to the wedding and evening waistcoats in 1840 and remains a mark of a quality waist covering to his day. The under-waistcoat, a Regency novelty, died out by the 1850s due to the shortened waist previously mentioned. (Illustrations from later in the era show what appears to be a slipped waistcoat, a pseudo under-waistcoat now more commonly associated with morning dress.)

Pantaloons and Trousers

At first, pantaloons – tight fitting and short enough to display the foot and ankle – were the norm and trousers were allowed only for less formal evening occasions. Over time, trousers became acceptable at all evening functions although they remained more fitted than day trousers. The foot straps introduced in the Regency era passed out of fashion during the 1840s.

Originally, evening trousers were black kerseymere or sometimes cashmere but by the 1860s they were made were made of the same wool as the tailcoat. Like the tailcoat’s adoption of silk facings, trousers began to sport military-inspired ribbon braid on their outseams in the 1850s.

Shirt & Collar: Ruffles Give Way to Pleats

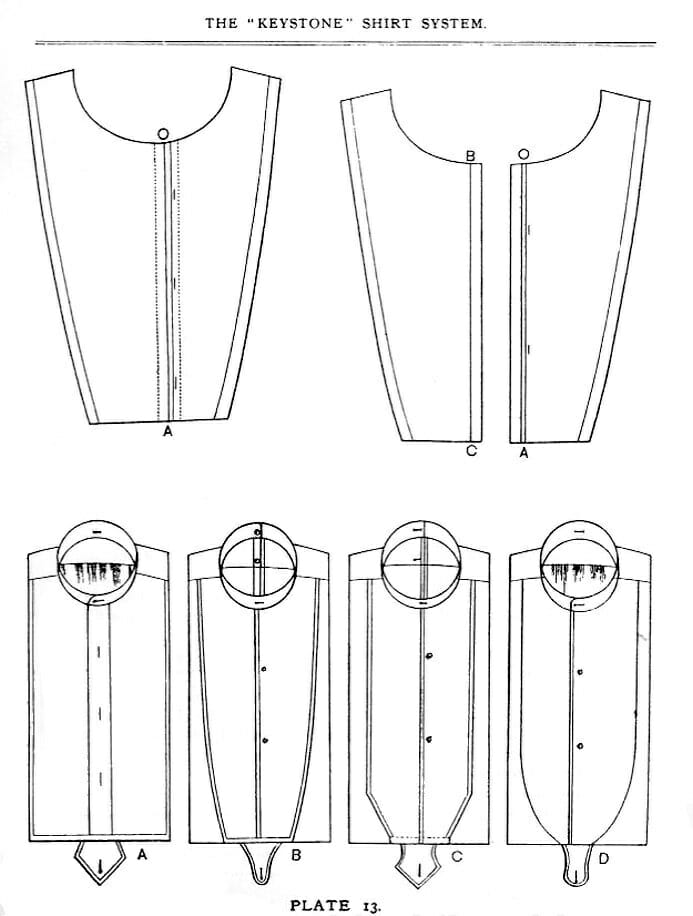

Ruffled shirt fronts were increasingly rare throughout the Victorian era as delicate pleats became the decoration of choice. Plain fronts were the most common style by the 1850s and required a thick bosom to maintain an unrumpled appearance on a shirt that otherwise fit very loosely. Eyelets began to appear at the same time to accommodate studs and starched cuffs made cufflinks more fashionable.

Stiffened upright collars appeared in the 1860s and began to display wings in the following decade. Turndown collars were occasionally seen in the 1860s and early ’70s.

Neckwear: From Cravats to Bow Ties

The standard evening neckwear was a white cravat at first then by the 1860s, a white “neck-tie” or bow tie, all in washable material. In America, black ties were equally acceptable but in Britain, they were relegated to the least formal affairs. By the 1860s, evening bow ties were generally narrow and featured pointed ends.

Early Victorian Footwear

At first, evening footwear continued to be black dress boots or pumps although they were now being specifically described as patent leather. In 1857, The Fashionable Dancer’s Casket reported that “Shoes, or pumps, have gone out, excepting at State balls, where court dresses are worn.” Boots were now the foot covering of choice.

Evening stockings were generally black silk although some period illustrations show white silk hose making occasional appearances throughout the Victorian era.

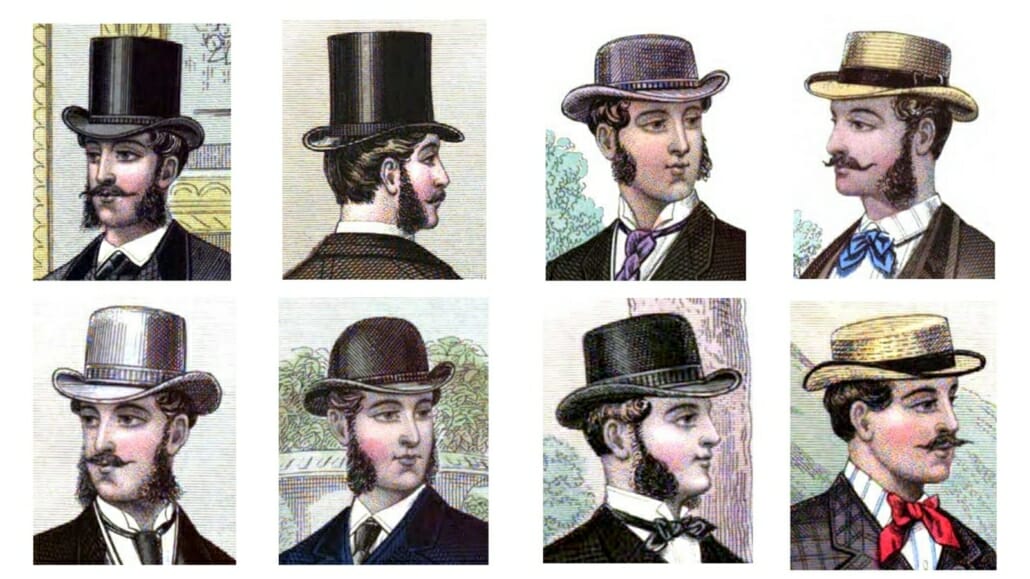

A Plethora of Hats

According to the 1839 Handbook of the Man of Fashion, “At a dance or large evening party, chapeau bras is appropriate and elegant; but to carry a common hat on such occasions, as is done by some awkward imitators of fashion, is clumsy and absurd.” The “common hat” mentioned is the top hat which by the 1840s “had changed from a fashion novelty to a status symbol for bourgeois men,” explains the McCord Museum’s Web site. “The top hat symbolized respectability, wealth, dignity and social standing: High and imposing, it made men look taller and ‘handsome.’

Although acceptable for evening wear, the black top hat was impractical not only because of the aforementioned awkwardness when carried but also for its susceptibility to damage when stored under a gentleman’s seat at the opera or theater. Consequently, when Antoine Gibus perfected the collapsible version of the top hat around 1840 the resulting gibus hat quickly became the most popular headwear after six o’clock.

Originally common in beaver fur, the top hat (aka topper) was increasingly popular in silk hatter’s plush thanks to advances in silk hat construction, the significantly lower price, the style’s adoption by Prince Albert in 1850 and the depletion of the North American beaver by mid-century. For this reason, it was also frequently known as a silk hat.

Early Victorian Gloves & Outerwear

Gloves

The use of evening dress gloves evolved from mandatory – “the ungloved hand is the cloven foot of vulgarity” (1839) – to recommended, particularly when dancing – “to touch the pure glove of a lady with uncovered fingers is impertinent!” (1857) – to optional – “this fashion of uncovered hands originated among English royalty, and it finds favor with many of the leaders of American society” (1878). Regardless of the necessity, one protocol remained firm throughout the period: gloves must always be removed for dining.

Dark or pale colors were acceptable for ordinary evening wear but at very formal occasions such as balls, gloves were required to be white or possibly pale yellow, also known as buff. The luxurious properties of kid leather made it the perfect material for evening gloves.

Outerwear

According to the Handbook of English Costume of the Nineteenth Century, both cloaks and overcoats were worn with Victorian evening wear, the latter becoming more common over time.

Other

Now that evening waistcoats featured pockets, it was acceptable to store watches in them as was the fashion with morning dress. Attached to the timepiece was a decorative chain which fastened to a waistcoat button to prevent the watch from falling out of its storage place. This watch chain or watch guard could be embellished with valuable trinkets or mementos at first but by 1878 authorities were cautioning that less jewelry “always looks more manly and aristocratic than a superabundance of ornament.”

Shirt studs and cufflinks were another new addition to evening wear. Etiquette mavens recommended that the studs and sleeve-links be kept small and simple and favored ones made of turned gold or decorated with diamond, black pearl or opal.

An 1857 American etiquette book suggested a “soft, thin, white handkerchief” be carried with evening dress and a number of period British manuals referred to scenting this accessory with perfume.

Ready for Relief: Contemporary Critics of Victorian Formal Dress

Evening dress may have been virtually obligatory in the nineteenth century but that doesn’t mean it was universally loved. One of the most popular etiquette authors of the Gilded Age shared his surprisingly frank opinion of the outfit:

It is simple nonsense to talk of modern civilization, and rejoice that the cruelties of the dark ages can never be perpetrated in these days and this country. I maintain that they are perpetrated freely, generally, daily, with the consent of the wretched victim himself, in the compulsion to wear evening clothes. Is there anything at once more comfortless or more hideous?

No doubt this writer was not the only Victorian male to resent dressing up in a formal uniform six nights a week. Day wear had been made significantly more comfortable with the advent of the common sack suit and it was high time to devise a similar solution for evening apparel.

Dress Decorum & Formal Facts

Dress Decorum: U.S. Formal Daywear

Early American etiquette books went to great lengths to explain why a dress coat before dinner was highly inappropriate “on anyone but a waiter.” While most of society’s elite understood that morning dress was the only formal attire correct prior to six o’clock, the masses never overcame their perception that evening wear was all-purpose formal wear, resulting in today’s peculiar American phenomenon of what could best be described as daytime “waiter weddings”.

Formal Facts: The Social Season

The social season, or simply “the Season”, was the time of year when society’s elite would leave their country estates to reside in the city and attend grand dinner parties, charity events, and debutante balls.

According to Debrett’s, the London season ran from April to July and from October until Christmas. It commenced each year with the opening of the opera season at Covent Garden.

The New York social season began in November with the National Horse Show and the start of its own opera season and lasted until early summer.

Formal Facts: Opera Etiquette

Entire chapters of Victorian and Edwardian etiquette manuals were devoted to the intricate social maneuvering that took place at operas among the wealthy owners of private boxes.

Dress Decorum: Codified Attire

During the Victorian and Edwardian eras, men of means were highly conscientious in dressing according to occasion and time of day. This required a wardrobe of formal day and evening wear, lounge suits for casual outings and a seemingly endless array of outfits designated for specific sports and leisure activities.

Formal Facts: Shirt Tabs originated in Victorian times

The tab at the bottom of these shirt bosoms were a mid-Victorian invention that buttoned to the trousers and prevented the garment from riding up. At the time, shirt fronts were stiff, and the shirt tab ensured everything stayed in place no matter if you were seated or stood up. Quality tuxedo and white tie shirts today still have that very same feature.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie