Neckties have a common place among men around the globe, yet they serve no practical purpose and are merely decorative.

What became known as “the tie” approximately three hundred years ago has been in existence for thousands of years, dating as far back as the dawn of human existence.

Fashion experts, sociologists and other professionals have been contemplating the tie for years and how it has somehow become the pinnacle of business attire. While many men dread the thought of having to tie the knot, others relish in the fact that they’re carrying on a proud tradition of formality, poise, and elegance.

To chart the tie’s appearance and determine its significance, we’ll go back in time to the antiquities when man first sculpted or painted early neckties prominently wrapped around their nape. Of course, this is only a brief overview of the history as entire books have been dedicated to the subject of the evolution of neckwear.

The Birth of the Tie

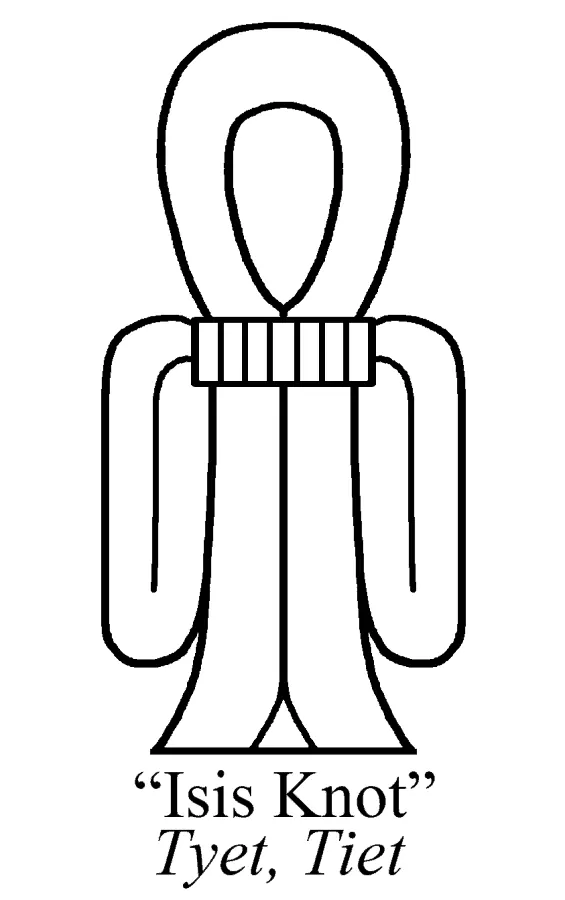

If we go back four thousand years to ancient Egypt, we can examine the necks of many Pharoahs and notice broad ties adorned with precious stones wrapped around their necks. Archeologists have found what is believed to be a talisman known as the Knot of Isis around the necks of mummies. It is called that way because it resembles a knot used to secure the garments worn by Egyptian gods and is much older than the terrorist organization that is associated with the world “Isis” today.

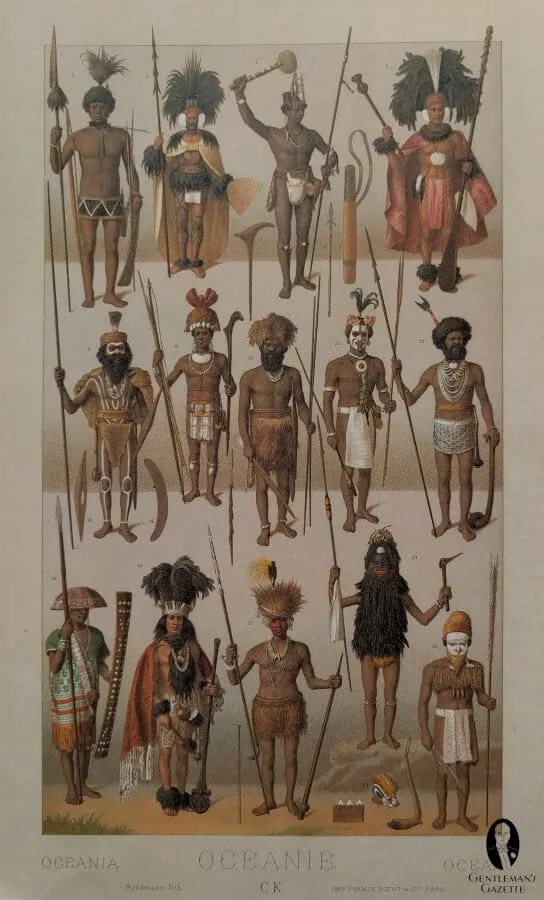

Even some Indios of certain tribes in the Amazon and Aborigines in Oceania wear very little clothing but neckwear. While it’s impossible to establish the specific time that modern man began to wrap knotted fabric around his neck, it is evident that neckwear has a tradition on a global scale and not just in the Americas and Europe.

In the wake of the upheavals of the Thirty Years War, Europe introduced the necktie as we know it today. While the tie’s predecessor, the scarf, was notably present before the war, it is still difficult to build a timeline and determine the exact history and progression of the necktie.

The Scarf Came First

What little we know is that scarves were documented to be in use on two occasions historically in different civilizations. Interestingly enough, apart from simply knowing the dates, there is no knowledge of scarves being used in earlier or later periods at all.

Theory I: The Scarf As A Badge Of Honor

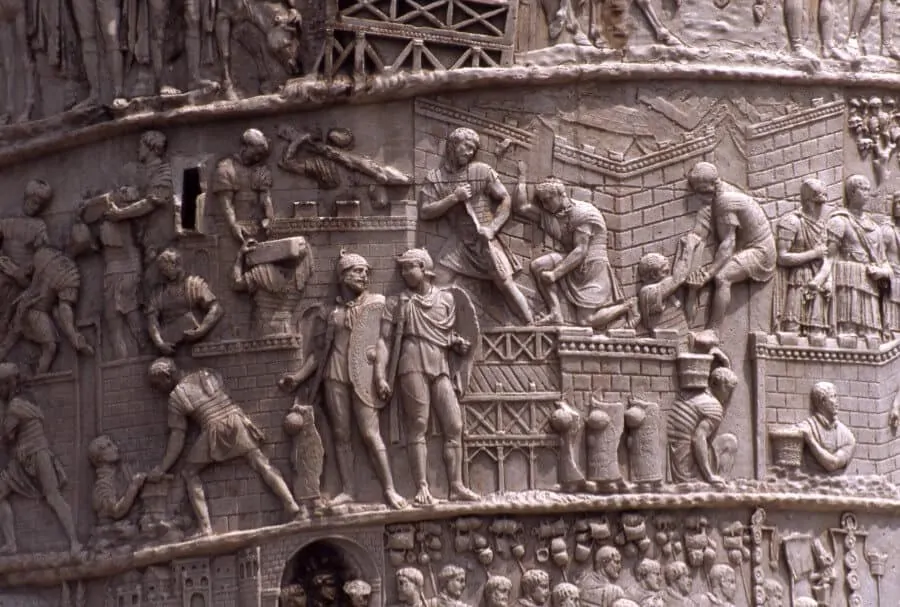

Legend has it that the scarf as we know it today was introduced by the Romans based on the Column of Trajan, which can be found close to the Piazza Venezia in Rome. The column was erected by Marcus Ulpius Traianus in the year 113 AD, and it features a scarf that was called a “focal,” which is unusual. According to written testimony, it is said to have been made of wool or linen, but that’s all we know.

Interestingly, some the figures have what appears to be scarves draped around their necks. Many of the imperial legionaries have these decorated scarves tucked into their cast armor whereas others simply have them tied, reminiscent of the American Frontier.

As such, it seems that scarves were not worn by the general public but only by soldiers as a badge of honor.

Theory II: The Scarf As A Symbol For Sick People

Other sociologists believe the scarf was a symbol of sick people.

The Terracotta Warriors Wore Scarves First

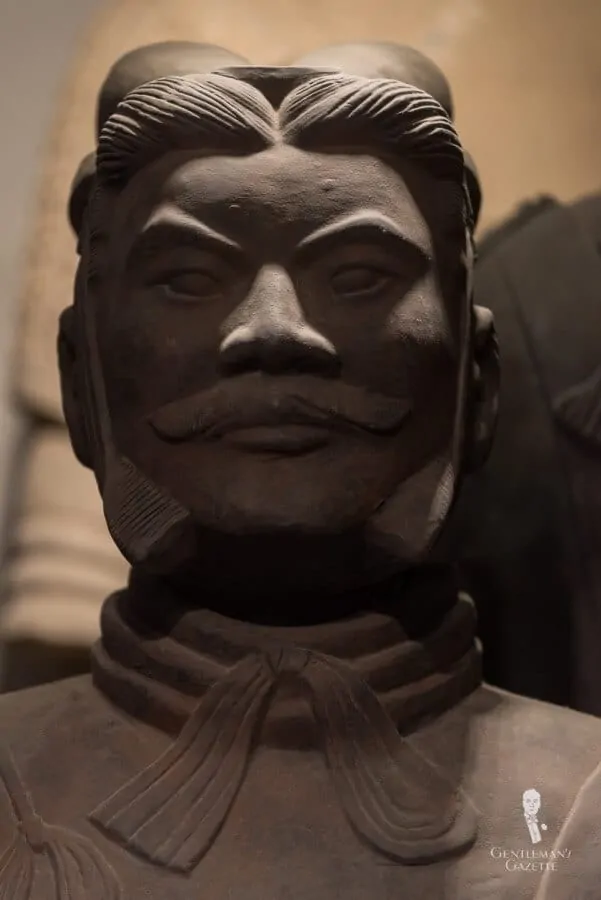

In 1974, the ancient tomb of Qin Shi Huang was discovered. He was the 1st Emperor of China that died 210 BC and was buried in spectacular fashion. Along with him, the famous Terracotta army was found. In the reigns of rulers prior to Qin Shi Huang, it was common practice to kill the entire court upon the death of the ruler, so they could accompany him in the afterlife. Since the population of Huang’s time had been decimated by war, it was decided to send along terracotta warriors into to the tomb instead of real soldiers.

Surprisingly, these soldiers wore broad scarves wrapped around their necks as you can see in the pictures. While regular soldiers wore what looks like a scarf that was tucked into their suit of armor, officers wore elaborately tied neckcloths.

So more than 300 years before Trajan’s legionaries wore scarves the Chinese had already used neckwear and, therefore, we know the Romans were not the first ones to wear a scarf.

It is believed that the Terracotta Army wore scarves to prevent irritation from their armor as well as to protect them from the cold.

Scarves in Buddhism

Traditionally, it is common practice to give a silk or white cotton scarf to people of a certain socioeconomic standing when visiting a temple or shrine. This custom is still prevalent today and stems from the practices of the shamanistic divinities in the pre-Buddhist periods.

The Necktie as We Know It Today & The Croats

If you look up the word tie or necktie in an encyclopedia, you’ll find that it tells us that the tie as we know it today was invented by the Croats. The word Croat which stems from hrvat, and eventually it evolved into cravat.

The Tie & The Thirty Years’ War

In 1618, Sweden and France joined forces against the Habsburg Empire, resulting in a war that lasted thirty years. During that time, the cravat came into its name. Many believe that the Croatian troops serving under the King Louis XIII of France tied a wide collar in a knot, whereas others believe that it was the German army serving under Ferdinand II responsible for creating the cravat.

So, who actually invented it?

During the thirty years war, the troops descending from Croatia, Hungary and Bosnia were all known as Croats. They were mercenaries, willing to enter battle and fight on behalf of the highest bidder. Louis XIII of France enlisted many of these troops.

However, they swore no allegiance to the King, nor to each other, and, therefore, many of them also battled against the French, especially in Flanders, under the command of Ottavio Piccolomini, a Florentine mercenary paid by the Habsburgs. So obviously, Croats were on both sides of the battlefield.

As such, it is unclear if the French or the Germans were the first to adopt it. However, what matters is that from 1650 onwards, scarves, jabots, and bow ties appeared with consistent regularity as a badge of nobility.

Of course, one could also examine if the Jewish tallit was similar to a tie, or if knights during the middle ages wore scarves underneath their suit of armor… Aside from the fact that the neckwear would have served a practical rather than a decorative purpose, it doesn’t matter unless you are a historian.

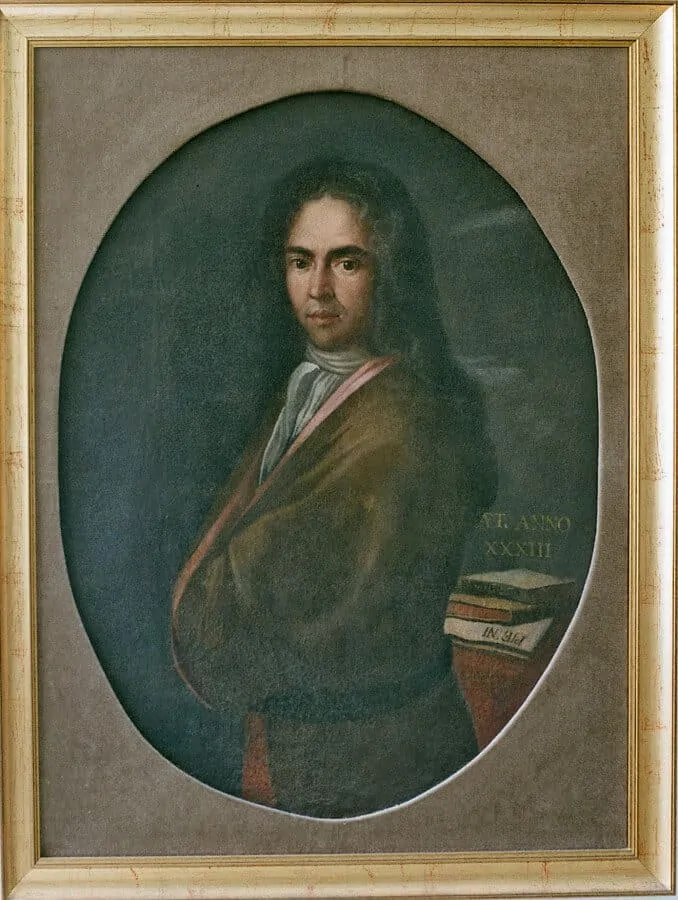

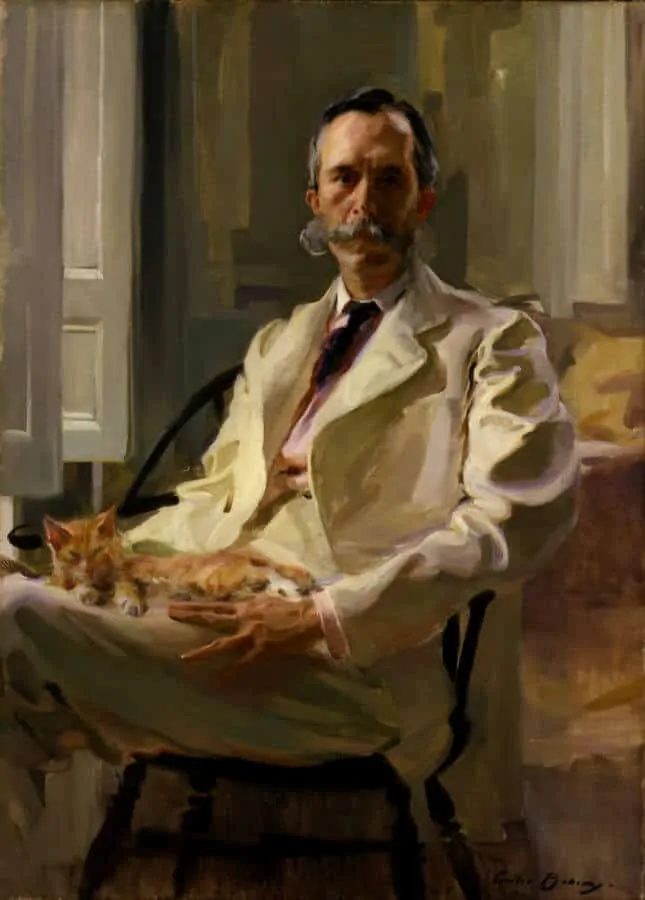

While there are no paintings that show Croatian mercenaries wearing cravats before 1620, artifacts uphold the theory of the Croats inventing the cravat and starting in 1650s many paintings show gentlemen wearing the cravat as we know it today.

By then, neckwear had officially become a fashion statement for men wanting to project power, wealth, and elegance. No matter where one lived in Europe, no man would dare have his portrait painted without wearing some form of neckwear.

The Stock Becomes The Neckwear of Choice in the 18th Century & Is Abandoned

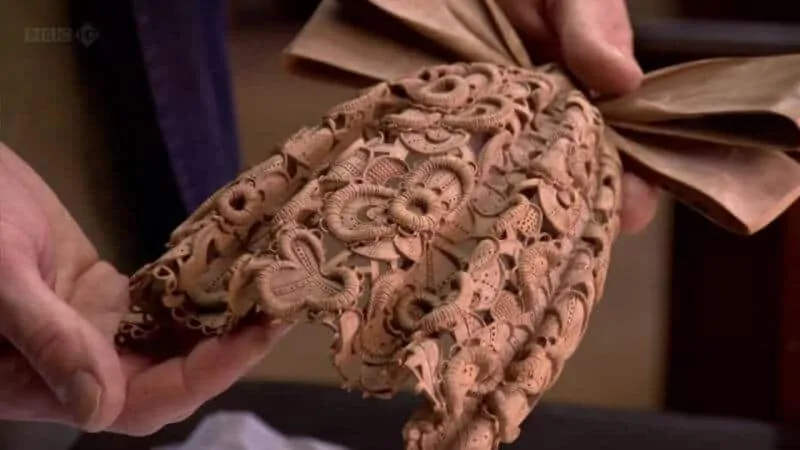

While the original cravat was a neckcloth for aristocrats that was made of white lace, muslin or linen that had to be laundered and pressed often by servants, the stock became the neckwear of choice in the 18th century. The stock was a simple high collar made of horsehair, whale bone, pig bristle or wood covered in cloth. As such it was very uncomfortable to wear yet easy to put on, unlike a cravat. It also was easily replaceable and was more resistant to soiling, which is why soldiers had to wear it, even though the fit was often terrible and it even impacted the soldier’s health and ability to fight.

Interestingly, by 1780 most men across Europe had abandoned the uncomfortable stock and had returned to wearing a cravat. The first to adopt this new style was a group of young British gentlemen who founded a club in 1764 and called themselves the Macaronis. They believed that menswear should be simpler, plainer, less restrictive and less decorative than in the previous century. It would be interesting to compare this attitude to the Duke of Windsor’s ideals, but that would be a question for another time.

Brummell and the Dandies: 1800 – 1830

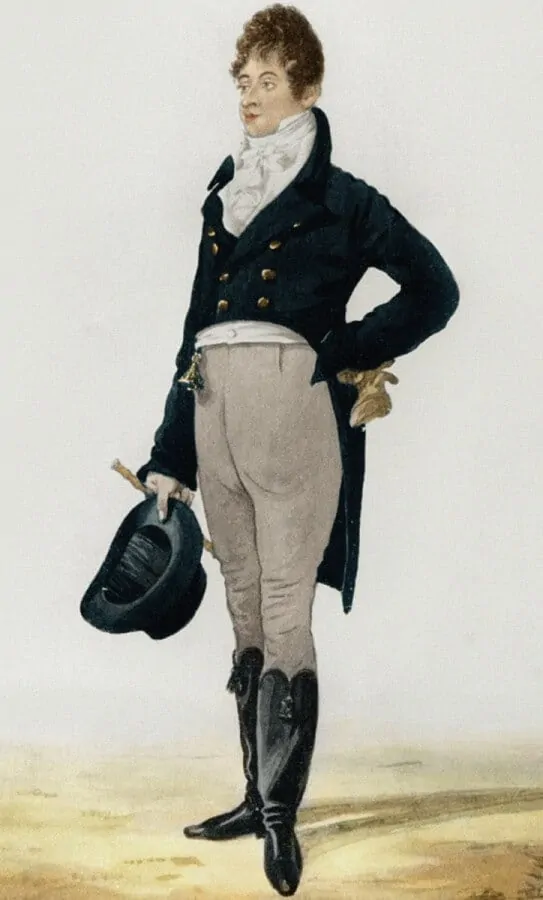

By the end of the 18 century, lace, brocade and satin were passe in menswear, so what was a gentleman supposed to wear? Of course, the most prominent dandy of the era, Beau Brummell, had the answer: a tightly fitted tailcoat, pantaloons, riding boots and most importantly a linen cravat that was tied over the course of hours so it looked like it was tied nonchalantly in just minutes.

This kind of uniform was accessible even to the middle class, which Brummell originated from, but it also allowed to upper-class gentlemen to express their wealth in details. As such it was a democratic fashion trend. In the same vain, Brummell introduced black for eveningwear, and which alongside white is still the preferred color for eveningwear today.

More importantly, under Brummell’s sartorial reign, the finely knotted cravat became the hallmark of a truly fashionable man.

The Cravat

The cravat, as an example, which was nothing more than a lace scarf, running parallel to the history of the wig, which it owes its success to.

Since the importance of men was often determined by the size of their wig, King Louis XIV was, of course, adamant that he must have the largest wig of all. Since many of this wigs fell past his neck and shoulders, there was such limited space for his collar, and with his flair for fashion and decoration, he began to wear cravats.

The Role of the Cravatier Evolves

The cravat he wore was made of lace imported from either Flanders or Venice, and it became the responsibility of the staff member assigned to the kind’s toilette and wardrobe to procure them. This role was highly coveted, and the individual fortunate enough to be tasked with it was given the extraordinary title of “Cravatier”. His duties included laying a tray out for the king with cravats for his choosing, each decorated and adorned with colorful ribbons.

While the Cravatier was responsible for the selection, the king took great pride in tying the know himself, while the Cravatier observed and added the final touches, ensuring it was straight and well tied for someone of the king’s royal magnitude.

History has shown that these cravats often featured bows that were sewn together and worn overtop. However, in other instances, the bows did not appear. While there is concrete evidence to support the rules around this, many historians believe it was solely based on the king’s mood that day.

Wooden Neckwear Is Introduced As A Joke By Horace Walpole

As these cravats were often tied in a bow that formed almost, a Lavallière. At the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, a wooden engraving is displayed by the master woodworker Gringling Gibbons, belonging to Horace Walpole, who wore this cravat as a joke one evening in 1769 at a formal reception in honor of some very illustrious French guests. Despite it being nothing more than a humorous joke, servants at the reception became convinced that English gentlemen were now in the habit of wearing wooden neckwear.

1830 – 1870

When George IV died in 1830, the age of elegance and the stylistic dominance of aristocracy and court died with him. However, the next arbiter elegantiarum was not far away: Count d’Orsay emerged as a leader of style

The Count d’Orsay Introduces Color & Soft Silk Neckwear

Born in France, he emigrated to Britain with his parents and was introduced into society in 1821. After a grand tour for seven years with the wealthy Lord and Lady Blessington, he ended up marrying their 15-year-old daughter sight unseen in the prospect of snatching the Lord’s large inheritance. Four years into the marriage, his wife ran away and together with Lady Blessington he formed not only an illustrious, talked-about couple but also established the famous salon Gore House in Kensington, which is today the grounds of Royal Albert Hall.

Unlike Brummel, d’Orsay preferred soft shapes, and he exchanged the white linen neckwear for black or navy, sea green or primrose yellow silk satin cravat. He even dared to skip the neckcloth in the countryside which brought him admiration as well as disdain at the same time.

He was also the one who popularized black neckwear with a black coat and white shirt, and can hence be considered as one of the forefathers of today’s black tie tuxedo.

Neckwear Communicates One’s Social Status

Once Queen Victoria was on the throne, the middle class became stronger and wealthier and in the following a neckwear hierarchy evolved in the sense that it proclaimed one’s current position in society. The further a man had climbed the social scale, the quieter and more subtle his neckwear was, whereas the lower he was placed, the brighter and more varied his neckwear became.

Of course, it was also a means for men to express their desire for upward social mobility by wearing a tie normally designated for the next step up. In that sense, it was very similar to today’s philosophy of “dress for the job you want, not the job you have”.

The Stick Pin

With the popularity of the Cravat, another accessory flourished: the stick pin

Certain motives were more popular than others. Around the 1850s a horse shoe, fox head, pewter pot, crossed pipes, willow pattern and knife and fork pins were particularly widespread. By the 1870s initials, shells, coins, birds, flowers, etc. were often used as motives for stick pins, before pearls and diamonds made their way to fame at the fin de siecle.

The stick pin’s reign lasted until the 1920s when the traditional 3-fold four in hand tie was substituted with tie pins and clips.

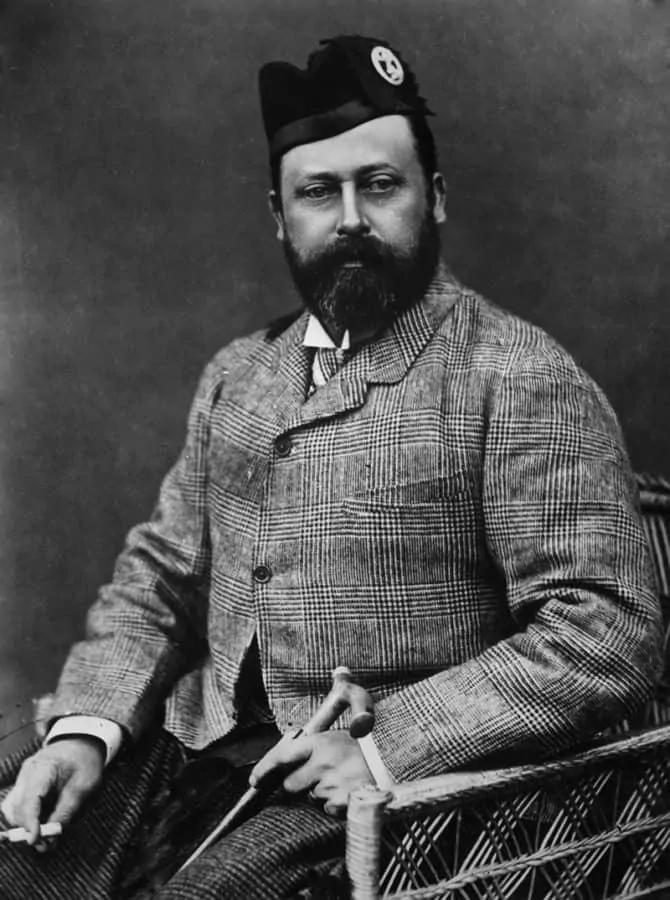

The Ascot

The tie stick pin was the accessory of choice to be worn with an Ascot. Basically, the Ascot emerged in the 1870s and took its name from the Royal Ascot horse race. Who or what exactly was responsible for this naming convention remains unclear. However, we do know that the Ascot was initially made out of silk foulard in lively colors that was 50″ long and close to an inch wide in the back, so it fit under a collar, whereas the ends were about 3″ wide, and square which were then sewn closed.

Another variation of the Ascot was made of silk foulard in lively colors, and it was worn puffed and held in place with a stick pin. Today, you may only see formal Ascots worn with proper morning dress at the Royal Ascot horse race, formal society weddings or costume parties and reenactment events.

The Four In Hand

By the 1870’s the Four-In-Hand Knot had surfaced and became a crowd pleaser very quickly. Interestingly, this trend was not only supported by the fashion industry but also by the military. In the 1800’s the British Army got rid of their brightly colored uniforms as they realized were a far too good target for the enemy. So rather than skipping color altogether, the regimental colors were transferred to the necktie, which looked very similar the one’s we know today.

Typically they were shorter and had a thin interlining but otherwise the shape clearly looked like a tie. In the 1890’s public schools joined in the tie craze, and so school ties were born.

At the time, short, untipped ties were the norm. Over time they got longer, and slimmer in 40s, 50s and 60s, before they became wider in the 70s and 80s. In the 90s most ties wear 3.5 ” wide and subsequently they got slimmer again. Basically, fashion is never constant, though a 3.5″ will always be wearable because it is timeless.

The Bow Tie Makes Its Mark

Around the same time, the bow tie became an established favorite among dapper men. First, the batwing bow tie, then the butterfly bow tie. But both weren’t new. However, the demand for colors in bow ties was a novelty.

The Beginnings of The Bow Tie

In the beginning of the 18th century, the bow tie began to be in a similar shape and size as it’s found today. It was during the Rococo period that the sizes of wigs began to diminish and were tied into a pigtail. For those who were not of nobility, or simply more meager means, wigs were far too expensive to purchase would grow their own hair out and tie it back in a pigtail. As wigs began to be viewed as effeminate, the wealthier members of society began to replicate this fashion. In order to tie the hair, they would use a ribbon and bow that was then drawn around the neck and knotted in another bow which was worn around the bare neck or a starched collar.

This single bow became known as a “solitaire bow” which helped to distinguish it from the other styles popular at the time. As such, even ordinary people began to wear material tied around their neck in bow during the latter half of the 18th century.

Following a revolution, British dress was streamlined and the men cast aside bright colors in favor of black dress coat and tails. It became that men began wearing jackets and trousers, ridding themselves of what was deemed to be ridiculous attire, which included the wigs and face powder, the bows and the lace. The only left remaining was the cravat which became a man’s only way of introducing a certain amount of flair or a touch of color to his everyday dress. Only the dandies of the time wore waistcoats, but for the most part they were concealed. All that remained was cravats that protruded from under frock coats and redingotes.

Now that the period of lace had perished, neckwear became very defined and was wound around the neck similar to a scarf to build height in an effort to complement the very high collars that nestled against a mans cheeks. It made the neck appear to be in a vice and the cravat was tied in a bow or a Gordian knot.

Never Wear Ready Made Bow Ties

In 1900, the book Clothes And The Man was published by the pseudonym “Major”. It provided details to the necktie enamored, Victorian middle class how to tie a necktie properly and how to combine them with shirts and what materials to choose. When it came to bow ties, the major was very clear:” Of course, no gentleman ever does wear a made-up tie, and doesn’t want the credit of wearing one.” He remarks further: ” I consider it the duty of every father to his son this on leaving school; it would save him a great deal of heart-burning and anxiety in after life.”

In case your father didn’t teach you, you must watch our video on How To Tie A Bow Tie. Interestingly, the book was continued in its style until the 1960’s.

The Business Of Tie Knots

An industrious man by the name of Stefano Demarelli realized there was an opportunity to be had, and began to offer courses on how to knot various types of neckwear. With each course lasting six hours, he charged nine Liras an hour to each attendee. Men came from everywhere and the dandies charged exorbitant amounts of money for the latest knots and style tips.

The First Bestseller On Neckwear Tying Appears in 1827

In the year 1827, a book was published in a small print shop in Paris called “L’Art de Se Mettre la Cravate”. This pamphlet was really the first of its kind as it became what we now consider one of the very first international best sellers.

In a period where most publications were useless and about trivial, insignificant subjects, this book proved useful to the man interested in tying neckwear and it was subsequently published in Italy the same year, and England the year after.

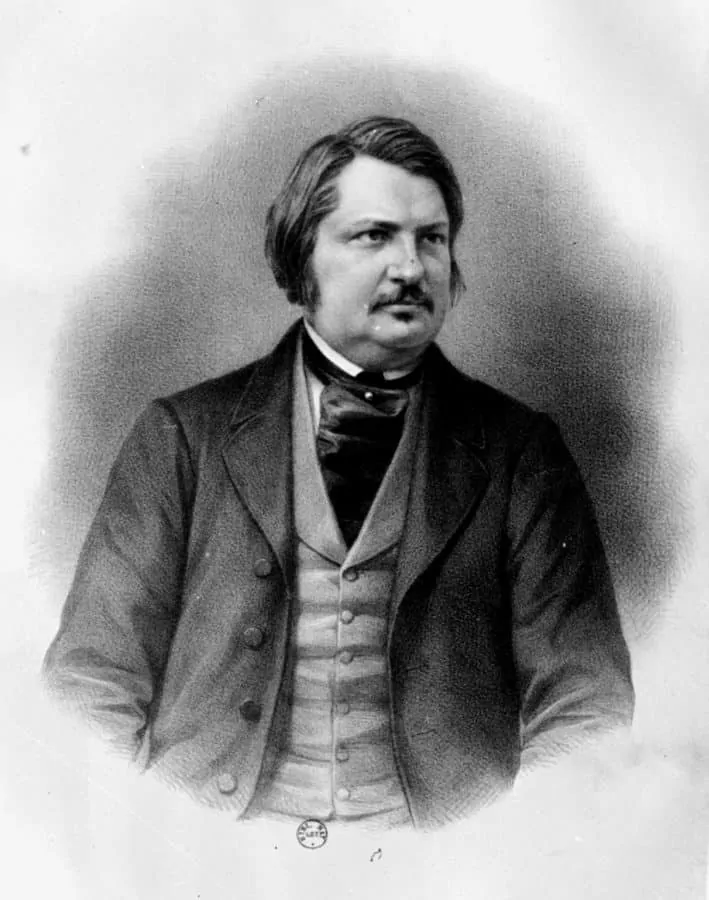

Balzac Pays His Tie Debt In A Creative Way

Until recently, most historians believed that the book was actually the work of several contributing authors. However, if we examine the “names” of these alleged authors, we quickly notice something very interesting. When the book was published in France, it was credited as being written by Baron Emile de l’Empésé. When it was published in Italy the byline was Conte della Saida. A year later when it was published in England, the author was listed as H. Le Blanc.

For those who speak the language, you quickly notice that the word empésé means “starched” and saida means “starch” whereas, le blanc clearly means white. All of these terms can easily be references to the collars worn in those days.

While it may seem like a coincidence, the printing house that published the works was owned by Honoré de Balzac. It happens that at the time, Balzac purportedly owed money to a number of creditors who were tie and shirt makers. When we examine the list of recommended manufactures, the list appears to be none other than the creditors he was indebted to. For this reason, some believe the book was a way of settling the debt.

For those who are still uncertain, it should be noted that in addition to this book, Balzac also published a series of other books including ‘The art of paying your debts and satisfying your creditors without paying out a penny‘.

The Demise Of The Stiff Collar

By the end of the 19th century, stiff, upright collars gradually began to loosen and diminish in size. Doctors believed that stiff collars posed medical concerns for their patients and in 1917, a physician named Walter G. Walford published a book called “Dangers in Neckwear” where he claimed that ailments including eczema, headaches, vertigo, strokes, deafness and many other illnesses could be directly attributed to tight neckwear. He further claimed that be loosening the collar, one could swiftly recover from a variety of ailments.

It was then that the starched collars declined in popularity and soft collars began to find their way onto dress shirts. At first, they were detachable, just like stiff collars and eventually they were sewn on just as we know it from shirts today. Unlike today, a collar always demanded some form of neckwear, not matter whether it was a necktie or bow tie.

Conclusion

Now that we explained the evolution of neckwear stay tuned for our final part where we discuss the reason of wearing ties.

Why We Wear Ties

Despite ties being such a prominent accessory worn by men the world over, psychologists and sociologists have somehow failed to define the science behind the usage and customs as it relates to neckwear. In fact, not only is the science unclear, but for most, it downright baffles them.

Ties Are For Decoration – That’s It

Unlike the vast majority of clothing we wear, ties are completely decorative and serve no practical purpose. Most items we wear are utilized first and foremost as a tool to either protect us from the natural elements such as heat, rain or snow and to meet cultural clothing standards. Surprisingly, ties provide a contrasting alternative. Even scarves which are the ancestors of neckties and bow ties had a use, offering the wearer protection against weather. Men simply don’t use a necktie to keep warm.

The Tie – A Phallic Symbol for Sexuality?

One theory behind the popularity of men’s neckwear comes from the book The Psychology of Clothes by J.C. Fluegel, in which he suggests that they can be considered phallic symbols representing a man’s sexuality and masculinity. When the British Clothing Industry Association sent out a survey to a selected group of men, almost four hundred responded validating Fluegel’s claim, agreeing that they thought of neckwear as being a sex symbol. They furthered this survey by placing an advertisement in The Times, asking members of the public to reply with their opinions of ties. After receiving hundreds and hundreds of responses from readers, it was concluded that more than half of the replies contained blatant sexual undertones. In fact, one woman wrote that “a man, by taking off his tie, performs a very erotic act”.

It would far too simplistic to exclusively interpret and categorize neckwear as sexually desirable. Many men wear a suit and tie, regardless of whether anyone will see them or not, simply because it makes them feel a certain way, while on the flip side men of the opposite opinion wear ties only when necessary.

Power Ties

However, it’s not just wearing the tie that can invoke these attitudes and feelings, but also the type of tie, the color and the way you knot it. There is a reason certain ties are considered to be “power ties” or “elegant”. Based on our attitude or mood, we as men tend to choose our tie accordingly. A jacquard woven tie with fine patterns in bold red, blue or yellow shouts “look at me” whereas a muted madder tie or wool challis blends in more subtly into the ensemble, while a knit tie evokes a more casual character. We knot it in a variety of ways based on the look we want to project, hence the mirror or reflection of who we are. We’ll choose a bow tie for a night to the opera, but a windsor knot to necktie if we need to protect confidence and power. One could even say that the way one knots his tie showcases the attitude better than any other form of biographical study.

Psychology of Ties

Even the tightness of the knot is a reflection of who we are. A loosely tied knot can often be attributed to someone who is kinder and more jolly, or just sloppy, which is one reason why salesmen are often encouraged to utilize larger knots. On the other hand, small, tight knots can be seen as uptight or a sign of sophistication. For example, Prince Charles is a huge fan of small tie knots with thin ties and it suits him very well. Interestingly, studies have shown that people are more inclined to approach a man with a large and loose knot over someone with a small, tight knot simply because they’ll perceive him to be more inclined to communicate, less selfish and more helpful.

That being said, studies have shown that people are often more inclined to approach a man with a large and loose knot over someone with a small, tight knot simply because they’ll perceive him to be more inclined to communicate.

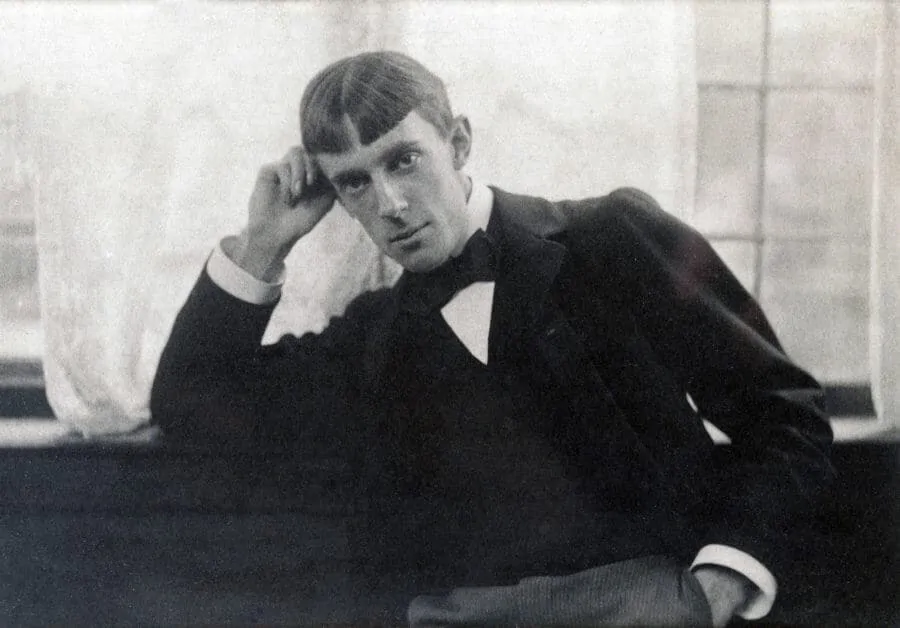

Knots Make A Statement

Even though men can in theory choose from dozens of tie knots, most men will only have one or two that they fall back on. For most men, that’s because they don’t know any other knots. However, more elegant men know how to tie different knots but often they have determined what knot works best for their tie collection, height, profession and look they are going for. Nevertheless, once someone is into men’s clothing you can exactly see that they not only carefully chose a particular tie construction and material but also a knot, with a dimple and sometimes the back blade sticking out from the side, to signal “I am in the know and different than Joe Average”.

Colors, Materials & Patterns Maketh The Tie

Certain colors are often associated with various moods and character traits. Yellow or gold ties often get referred to as a power tie, purple ties as regal and blue or red as patriotic – especially in America. Just think about the presidential TV debate – when did you see someone wearing a burnt orange, plum or bottle green tie? Probably never. In fact, a good defense lawyer will always recommend that his client wear a blue tie because it invokes feelings of trust and honesty. This rule also applies to why many politicians and world leaders choose blue ties during public events.

For the more sophisticated tie wearer, more unusual colored ties are a desirable departure from the simple, bright colored neckwear that can be found anywhere. Wearing a tie a dark shade of turquoise, rust or chartreuse underlines that they are different in a unique way – they don’t just follow the trends, they set their own tone.

Twenty years ago, Silk Ties were the standard and maybe you could find some wool or cotton ties on occasion. Today, you can find all sorts of blends, and weaves that help men to make them unique. At Fort Belvedere, we always strive to create unusual, unique ties and bow ties that you cannot find anywhere else because we want the tie to be as special as its one-of-a-kind owner.

In Britain, a regimental tie signals that you are a member of a regiment, university or organization. Outside the UK, most people have no clue about the exact signal of that particular tie or pattern, but they associate a certain Britishness with it and wearers often choose them because of it. They want to be perceived as having classic British taste.

The more unusual and eccentric the tie, the more we assign those same attributes to his wearer. Many banks and financial institutions actually require their clerks and staff to wear only ties with small dots no greater than three or four millimeters across. The purpose behind this is that many believe anything larger is an overt sign of frivolity. At the same time, once one has achieved a certain rank within the bank, it becomes acceptable to wear Hermes ties with little elephants on them. At that point, everybody knows that a Hermes tie communicates “I made it” and it represents a certain status. As such it has very little or nothing to do with taste, it has just become a form of rank like epaulets.

At the same time, a solid light pink shiny satin tie with a big Windsor knot is likely the hallmark of a sleazy salesman, whereas a muted printed wool challis tie is more associated with a country gentleman. Everything that we choose in a tie sends a signal to others, and therefore it is important to understand what signal ones is sending because who wants to be perceived as lacking in taste?

Tie Faux Pas

Since there are so many ways to wear a tie, it’s important to avoid some key faux pas that will not make you stand out in a good way. For example, nothing screams for the wrong kind of attention more than aggressive ties featuring comic figures, super heroes, sports teams, LV or Gucci logos.

The same is true for clip on ties, pre-tied knots or tie knots that are loosened with open shirt collars. It looks sloppy and forced, like the mother has demanded that her son wear a tie. That’s never desirable because it makes you seem like you are not in control but controlled by someone else.

If you don’t know how to tie a tie, no problem, you can learn it here – it’s easy and won’t take long to learn.

Oriental (the easiest tie knot)

Four in Hand (the most common)

Preferential Treatment

In this day in age, some consider a tie a relic of the past, but ties still matter on a subconscious level. “Power ties” are worn to convey power, and confidence. Because fewer men choose to wear them, the assumptions people make about tie wearers are similar – they are successful, have a high ranking job or are from a respected profession. Even out of a professional context, a tie symbolizes masculine power in many ways.

Employers are often more inclined to hire applicants who wear ties to an interview over those who don’t because wearing a tie communicates respect of the position. As such, a tie is helpful for interviews. Even if you get the job without the tie, chances are you would have received a higher starting salary if you wore one.

Being well dressed, and wearing a tie often go hand in hand, and wearing one can result in many good things happen to you that would not have happened otherwise.

Conclusion

In the end, the tie is decorative and an element that is supposed to flatter its wearer. From “bad tie parties” to “black tie events”, ties are an important part of a gentleman’s wardrobe because they possess a big impact on how one is perceived, and it servers to complete one’s outfit.

Psychologically, you can find many reasons to wear a tie, though the best one is to express yourself.

Jacques-Louis David’s uniform sketches for public post-Revolution functionaries all seem to have dispensed with neckwear, interestingly (though they do have lots of other drapery). They almost look intended to showcase the neck, though it may just seem that way due to the shock of seeing late-18th-century collars without cravats.

It’s interesting to connect David’s 1791 self-portrait here with Brummell, although I’m not quite sure I’m sold on the idea. His loose coat and relatively natural hairstyle are showing off a Republican, simplified, anti-Rococo self-image, which does connect with your idea of the Brummell look as Democratic, but I think David would have been horrified at the idea of spending hours getting dressed. Though his costume designs do show that he thought about clothing–maybe a lot more than he would have admitted.

Interesting article. I had no idea about the complex origins of the scarf. Although, I was under the strong impression that Macaroni fashion referred to the flamboyant and effete styling of young gentlemen who had picked up influence from the ‘Grand Tours’ of Europe. They wore enormous wigs, and dressed in the highest fashion possible. Indeed Dandies are labelled as the elegant backlash to this borrowing from martial tradition and using a limited colour palate. I am interested where you learned what you have written, would you be able to direct me?

Hey I just want to correct you that the Huang’s soldiers are not wearing scarves, those are the neck part of traditional clothes back in that time. Google Qin Dynasty clothing and you will get a clue.

It doesn’t matter what you call them, but they are neckwear.

You seem to have missed the point, Raphael. My namesake has explained that what may look like scarves are not scarves but the collars of traditional robes

I would be interested to know, although I see that you have avoided a similar question below, how you ascertained the very exact date of 1764 when the group of young British gentlemen founded a club and called themselves the Macaronis

and how did anyone blackballed from membership of the club, and therefore not a Macaroni, describe himself?

A thorough and readable piece on an essential (for most) wardrobe item, Sven. bravo!