Resuming our tour of Northamptonshire boot and shoe makers, today I headed north to the quiet village of Ravensthorpe, where I visited a quite unusual and rather special artisan firm, Horace Batten Bootmakers Ltd. Ravensthorpe lies a few miles from Althorp, ancestral seat of the Spencer family and final resting place of Princess Diana, in rolling Northamptonshire countryside within the territory of one of England’s most famous hunts, the Pytchley. The Batten family have been making riding boots since 1804.

English riding boots are perhaps the finest in the world in terms of both craftsmanship and materials. This tradition endures by virtue of a handful of boot makers who make bespoke, or made-to-measure, riding boots as well as by a few companies selling ready-made models. Here, we visit Horace Batten Ltd, an old and well-respected artisan firm of riding boot makers. There is some background regarding fox hunting, but the article concentrates on the basics of boot making, rounding off with a brief overview of the principal riding boot makers.

The British Hunting Scene

Riding encompasses many disciplines: competition riding in its various forms (showjumping, dressage, endurance riding), Western riding (including cattle ranching and so forth), long distance riding and pony-trekking, polo, hacking-out, and – of particular interest to myself – there is also hunting. Nor should one overlook the continuing military and police activities that involve horse riding. Immediately, one perhaps has some impression of the widely varying types of outfit associated with riding, all reflecting differing traditions and sartorial requirements. Riding boots (which I feel sure are a subject of acute interest to many among the Gentleman’s Gazette’s readership) understandably vary in form also, according to the particular requirements.

My main interest in this regard is somewhat specialised: the hunting boot. Here in the UK, the debate over the rights and wrongs of fox hunting has rumbled on for a century and more, but I do not intend to be drawn into that argument here, save to observe that, regardless of its many opponents, and despite various efforts to put an end to it – most recently with the Blair Labour Government’s 2004 Hunting Act – fox hunting remains as popular as ever; indeed there are very few counties in England and Wales where, during the winter months, hunting does not take place several times each week. Riding to hounds imposes particular demands on one’s choice of clothing, and of footwear in particular. Most readers will be familiar with the traditional hunting ensemble which, while apparently unchanged since around the time of the 1832 Reform Act, is nevertheless highly evolved to meet specific needs, fundamentally concerning protection of the rider from various circumstances. Hunting typically involves long intervals spent waiting on the brows of rain-lashed hills, with sporadic high-speed cross-country dashes over muddy fields, hedges, ditches and other obstacles, and it is certainly not without its hazards.

First there is the intermittent risk of an involuntary flying lesson; then there are collisions with fellow riders, or with other sharp or immoveable objects such as trees, gate-posts, fences, thornbush hedges, dry-stone walls, abandoned agricultural machinery or metal railings, to be accommodated. There will also be occasional drenchings in streams, or from wet and windy weather, to factor in. Mud and stink, filthy, cold, cloud-darkened wet British winter weather, broken bones and sore fingers – I trust I am managing to convey something of the glamour of the British hunting scene?

The boots, naturally, take a real beating – slashed by thorn thickets and flying stones, crushed against gateposts, and attacked even by the corrosive sweat that steams from the flanks of one’s mount. The traditional riding boot is made from box calf; usually black, although tan or brown may be worn for autumn hunting. Only leather of a certain thickness is suitable. The hunting boot, a somewhat heavier-duty version of the riding boot and distinguished from other riding boots by a tan-coloured cuff, is made from wax calf – hide leather of a certain not insubstantial thickness which has been heavily waxed on the reverse side. A high gloss and easily restorable finish is eventually achieved by “boning” the leather with a deer bone. Wax calf boots are always black. Whereas dressage and showjumping boots often have curved (or Spanish) tops, and sometimes are zipped, hunting boots have straight-cut tops and are strictly of the pull-on variety.

Bootmaking Basics

I come to Horace Batten as an old customer; in 1999 I had a pair of riding boots made by Horace Batten himself, a remarkable man. He is now 101 and perhaps understandably has recently decided to moderate his involvement in the firm’s business, so today I am met by his son, Timothy Batten. Timothy’s daughter, Emma, also works for the firm, being the seventh generation of the Batten family to be employed in this way. I have brought my boots with me, having recently grown somewhat concerned by the toll taken on them by my riding and hunting antics. They underwent a fairly extensive resoling and restoration process a few years ago, but now in places the leather is wearing and beginning to crack a little. Mr Batten immediately busies himself with various oils and polishes to make good some of the wear and tear they have suffered – he reassures me that they will last quite a few more seasons, yet.

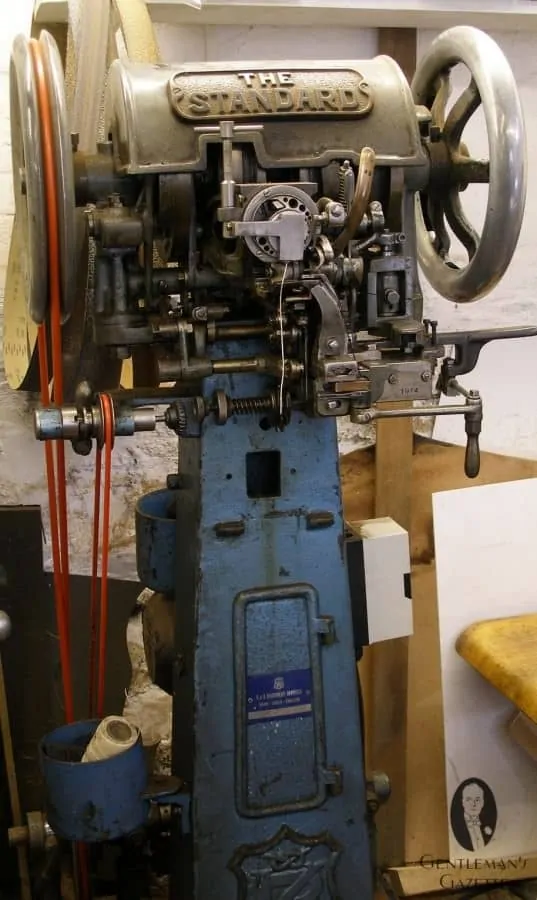

The Batten premises are not large; three rooms forming an L-shape, although plans are in hand to extend – at present there are eight staff, and a remarkable assortment of complex machinery, some of it specialist even by the arcane standards of the general shoe industry. Perhaps the most remarkable machines are two massive cast-iron blocking presses, used for shaping the uppers into the necessary upwards curve over the arch of the foot. They remind me very much of Victorian printing presses, of which they are perhaps distant cousins. The hunting season is just starting, so it has been a busy time lately. Mr Batten is firmly of the opinion that shoe-making and boot-making are complementary yet largely inimical activities. Although he himself does not hunt, he naturally is well placed to follow the hunting scene. Through his many customers, he has connections both with high-fliers in the City of London, and with the more arduous and certainly less remunerative world of the junior cavalry officer. And he also encounters those worthy stalwarts of the hunt, the whippers-in and huntsmen.

Timothy Batten’s office is a place of interesting character. The walls are lined with a great many riding boots – some are old, and some very old indeed. Trophies of the chase adorn the walls – antlers, foxes’ masks, as well as hunting prints of course; and there are tables on which are set out variations of riding boot, as well as orders awaiting despatch, and boots awaiting repair. Down to my right I notice a solitary chestnut-coloured boot that stands alone, the attached label reading: “Odd boot to be remade.” A one-legged rider perhaps? It emerges that it is a replacement boot for one (which I am then shown) that the medics had cut open, seemingly with almost criminal abandon, its owner having suffered some serious mishap from which he is now happily sufficiently recovered to wish to resume riding. The new right boot is being polished in such a way as to achieve the distinguished patina of its somewhat older left counterpart. Battens take pride in the graceful profile of their boots.

Clearly, it must correspond to a considerable degree with the shape of the wearer’s legs, and yet there is nevertheless a discernable Batten profile – slender and curved somewhat forwards, allowing one’s heels to be kept low while riding. While the foot is lasted, the leg is treed, using conventional multi-part wooden trees that are carefully adjusted by means of wooden wedges to achieve a match with the shape of the customer’s lower leg. Treeing the boots (which are first made wet) takes up to a fortnight. Ready-to-wear riding boots are normally made in a range of calf sizes, but understandably, even so it is seldom possible to achieve as close a fit ready-made as made-to-measure, to say nothing of the importance of correct height, whereby the top of the boot ideally should come to just under the small of one’s knee. The importance of close fit through the leg lies not just in elegance and comfort for the wearer, but in communication with one’s horse.

A first visit to Battens will normally involve, initially, a detailed discussion of one’s exact requirements. Battens make not only hunting boots and riding boots, but also polo boots, Jodhpur boots, canvas-legged Newmarket boots, as well as field boots and riding boots for officers of those few remaining mounted regiments of the British army – the Household Cavalry and the Royal Horse Artillery. Unless the boots are for hunting, there may be a choice of colour to be made – various shades of tan, mahogany and chestnut are available.

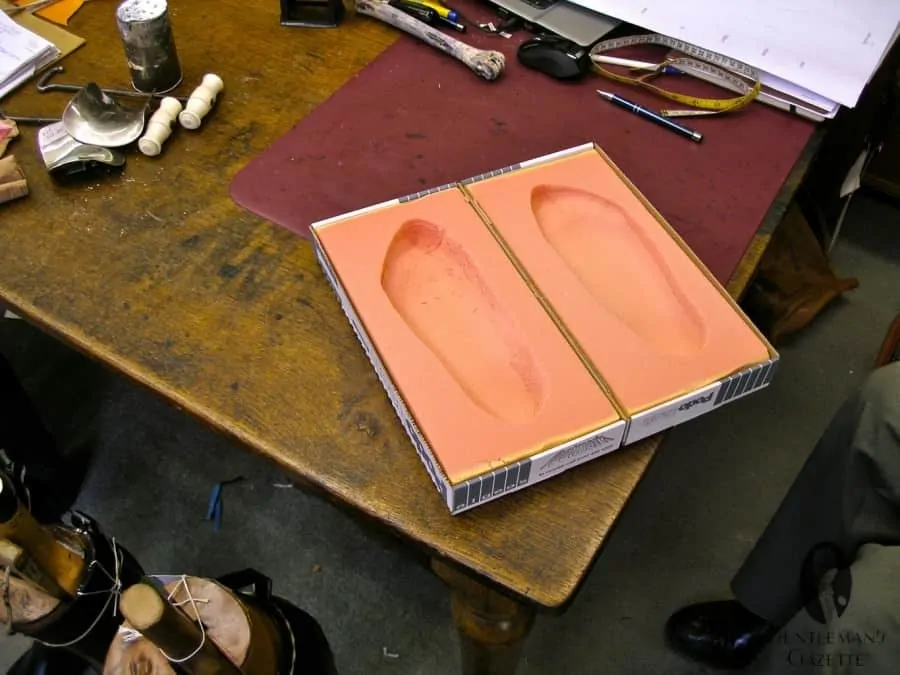

Having thrashed all that out, there is then a careful tracing and measurement of one’s feet and lower legs (and now – an innovation since 1999 – an impression of one’s feet is also taken), together with recordings of various other specifics. Ledgers dating back to 1952 retain all the necessary information for any repeat orders – in a matter of moments, the ledger for 1999 is retrieved, revealing my own measurements and correspondence. There is then a wait (two months at present) before one’s boots can enter production, then up to three months while they are made. Battens operate somewhat differently from most bespoke shoemakers, in that new and unique lasts are not made to one’s individual requirements, but rather a suitable last is chosen from the firm’s bank of lasts and then adapted and built up by means of leather fittings to produce a perfect fit.

There is some sense in this, because whereas a bespoke shoemaker may expect the average customer to order a new pair of shoes to be made from the same last perhaps every year or every six months, realistically even the most ardent foxhunter is unlikely to order more than three pairs of boots in a lifetime, and many will hope to make do with only one pair, so the expense of individually made lasts would perhaps be rather harder to justify. Henry Maxwell (who share Jermyn Street premises in London’s West End with Foster & Son) and John Lobb (around the corner from Maxwell’s) make lasts for each customer, but naturally charge correspondingly more (much more) – indeed the price of a pair of boots from these makers would be enough to buy a middling-to-good hunter.

The Batten Tradition

At Batten’s, The uppers are largely machine-sewn, using hand-powered and pedal-powered sewing machines that appear to be 1920s in vintage, but are possibly older. The box calf is all from Hermès-owned Tanneries d’Annonay. It is from young calves, for suppleness, but only from large young calves, in order that the leather is sufficiently thick – it must be no less than 1.6mm, yet pliant. In wordworking terms one might say that the seam where the vamp is joined to the boot shaft is butt-jointed. To the front, where the tongue of the vamp projects upwards, this seam is all hand-stitched and inverted so as to protect it from rubbing against the stirrup. On ready-made boots that I have seen, the junction of the vamp and shaft is (again resorting to the language of carpentry) lap-jointed, which is no doubt easier and faster to accomplish, but looks clumsy by comparison and exposes the seam to the likelihood of wearing.

Unlike the vast majority of Goodyear footwear makers (including even some of the better-known bespoke makers), Batten boots are hand-welted in the traditional manner – no fudging here with ribs and gemming – so as an additional and rare item of machinery there is an intricate device for cutting the groove in the leather insole, to which the uppers and welt are then sewn. Machine welting a pair of boots would be a matter of a few minutes at most; hand-welting takes half a day per pair. The sole leather that comes next is all supplied by Baker & Co of Devon, oak-tanned and supremely hard-wearing. The sole stitching, as one would expect, is channelled. Riding boots tend often to have thinnish soles, the perhaps understandable assumption being that they will do relatively little in the way of walking. However, when riding cross-country, most if not all of one’s weight is transmitted directly down through the legs and feet, which rest on the stirrups (in effect, rather narrow metal bars), and so my preference here, partly for aesthetic reasons, but mainly for comfort, is for my weight to be distributed upon soles that are rather thicker than those of, say, a pair of dress shoes.

Battens take pride in the graceful profile of their boots. Clearly it must correspond to a considerable degree with the shape of the wearer’s legs, and yet there is nevertheless a discernable Batten profile – slender and curved somewhat forwards, allowing one’s heels to be kept low while riding. While the foot is lasted, the leg is treed, using conventional multi-part wooden trees that are carefully adjusted by means of wooden wedges to achieve a match with the shape of the customer’s lower leg. Treeing the boots (which are first made wet) takes up to a fortnight. Ready-to-wear riding boots are normally made in a range of calf sizes, but understandably, even so it is seldom possible to achieve as close a fit ready-made as made-to-measure, to say nothing of the importance of correct height, whereby the top of the boot ideally should come to just under the small of one’s knee. The importance of close fit through the leg lies not just in elegance and comfort for the wearer, but in communication with one’s horse.

When the boots have been treed, the vertical seam that extends up the rear of the boot is only provisional – the backstay (the narrow strip of leather that will conceal and protect this seam) is not sewn on until after the fitting. Following the fitting, any discrepancies in fit can be attended to – for instance, the leg taken in, or more forcefully treed, to be let out; a pinching toe eased; or whatever. The boot will then be completed and finished. If trees have been ordered (they are essential for wax calf boots, to allow for deer boning), the boots will go off to Batten’s tree-maker, and then the whole finished job is despatched to the customer. An assessment of anything bespoke is such an individual thing – much depends on the maker’s interpretation of the customer’s wants, needs and desires, besides a grounded and thorough understanding of the customary use to which the bespoke thing is to be put. Bespoke riding boots are not commodities; each pair is unique, according to the size and requirements of the customer. Fit, naturally, is paramount.

Now consider the complexity of achieving a close, properly supportive fit to one’s feet and lower legs. Pulling on my riding boots for the very first time I remember was a strangely worrying experience – the fit is so close that riding boots must be tugged on, with some force, by means of hooks that attach to webbing pull tabs just within the tops of each boot. The foot must be made to pass through the more narrow throat of the boot just around the ankle; that first time, there was a slightly all-or-nothing moment involving a leap of faith that the foot would be accommodated. But the boots fitted, and have been perhaps my most comfortable footwear ever since. Admittedly, getting them off proved a bit of a struggle at first, and utterly impossible without the assistance of a willing assistant. (The recommended way of removing new riding boots is to recline into a comfortable lounge chair. One’s free foot is then clamped snugly between the upper thighs of one’s assistant, who is facing away. One’s other foot rests upon the assistant’s posterior, and pushes hard.)

As to the quality of the Horrace Batten workmanship, I have not found this wanting in any respect. The stitching remains tight, and despite various occasions when I have returned from a ride with thoroughly soaked boots, they have retained their shape and the leather remains supple. My boots are now approaching 15 years of age and, while (if I say so myself) they have been well cared for, always cleaned and polished after use, and have been resoled on one occasion, they have stood up well to some quite harsh treatment over that time. At the point just above the inner ankle bone, where the boot creases to accommodate movement of the foot, there is a tendency for it to rub against the girth and the horse’s flanks, and both here and further up the inner calf, where the leg rubs against the saddle, the leather is showing distinct signs of wear; but this is only to be expected.

The boots are not at all showy, in the way that some bespoke shoes can be – there is nothing about them (beyond the mere fact of their existence) that says: “My owner spent a lot of money on me.” (Even if he did.) They just look as one expects riding boots to look. However, a comparison with a ready-made riding boot would show up certain differences. The Batten leg will almost certainly be closer fitting – the correct fit of the leg is almost as close as that of the foot; ready-mades are invariably looser. And while a ready-made boot may (perhaps) be made of box calf of a similar thickness, it will probably be slightly older calf (to achieve the necessary thickness more economically) and will be less supple, hence less comfortable and also less able to transmit the feel of the horse to the rider. Or it may simply be made of full-grain leather.

Other Makers

During my visit to Sanders & Sanders, earlier this year, I was able to examine their Regent ready-made riding boots, with which I was in any case quite familiar – they are far and away the main ready-made maker of riding boots in the UK, and their Pro-Cotswold boot is in many ways an archetypal riding boot, sold at an attractively low price. I wore a pair once, and while there is no doubt that they are a good solid boot, once one has worn bespoke riding boots, a new pair of ready-mades will never feel as comfortable to wear. The other main British ready-made maker is Schnieder. Schnieder’s office and shop is in London’s West End, but the boots are all made in a factory in Clare Street in Northampton. While Batten make boots for the cavalry regiments’ officers, Schnieders have a contract with the Ministry of Defence to supply other ranks of the Household Cavalry with jackboots, as worn for the Trooping of the Colour in Horse Guards’ Parade. I have visited the Schnieder factory in the past, but in view of the company’s defence contracts, public access to the factory is no longer possible. Schnieder make quite an extensive range of ready-made riding boots, and they also offer a bespoke service.

There are of course many makers of riding boots – in Germany, France and Italy, there are firms such as Koenigs, Ariat, Cavallo, Brogini and de Niro. Reflecting the rather different traditions one finds on the Continent, their boots appear to be calculated to appeal more to dressage and show jumping riders, being made with softer leathers, so while they would do for hacking out, stylistically and in terms of construction they are less ideally suited for hunting. One other thing to be aware of also is that some “riding boots” are not meant for riding at all, but perhaps should be thought of principally as fashion accessories. For instance, I am prepared to believe that Hermès may make some real riding boots, but I understand they also make others that are strictly for the catwalk or boulevard. Be that as it may, for the rider looking for a pair of bespoke, wax calf riding boots, the choice probably comes down to four makers, all British: Horrace Batten, Schnieder, Davies and Henry Maxwell. At one time, Edward Green and Tricker’s also made riding boots, but no longer. I feel certain that in France, where there is also a strong tradition of mounted hunting, there must be some equivalent makers, while in the United States the choice would perhaps be between Dehner and Vogel, both of which make many different types of riding boot, although I believe only Dehner offer a wax calf boot. Having only ever been a customer of Horrace Batten, I am not in a position to make a fully detailed comparison with the other bespoke riding boot makers. The following table compares quoted prices of this shortlist of hunting boot makers, and it will be seen that there is considerable variation here, with John Lobb and Henry Maxwell being considerably more expensive. Quoted intervals between ordering and completion are also listed. Some perhaps are more bespoke than others; it is of course necessary to look in detail at materials and methods of construction, before reaching any conclusions on the basis of price alone. (For example, my understanding is that Davies boots are not Goodyear-welted, so repairs may be less easy to facilitate.) Some of the prices seem alarmingly high; however, transatlantic visitors might like to know that the prices include VAT at 20%, which is refundable when leaving the UK.

| Manufacturer | Box calf | Wax calf | Wooden trees | Time to make |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horace Batten (UK) | £845 ($1360) | £955-£1065 ($1538-$1715) | £450 ($725) | 5 months |

| Vogel (USA) | $1110 (French calf) | $1190 | ||

| Dehner (USA) | $1085 | $1250 | $725 | 12 weeks |

| Regent (UK) | £380 ($610) (ready-made) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Schnieder (UK) | £2670 ($4300) (ready-made) £3595 ($5790) (bespoke) | £1800 ($2900) (ready-made) £2500 ($4025) (bespoke) | £1380 ($2220) | 6-9 weeks |

| Henry Maxwell | £6000 ($9660) | £6000 ($9660) | Included | 12 months |

| John Lobb | £6246 ($10,050) | £6246 ($10,050) | £2025 ($3260) | 9-12 months |

Great article on riding boots. Boots amongst other things are a self confessed fetish of mine. I have nearly a dozen pair with one pair never seeing a horse, just looking cool with my other riding and hunting memorabilia beside the fire place… The price guide you have provided though seems a tad excessive. If anybody out there is looking for a really nice pair at a reasonable price, I strongly recommend RM Williams riding boots. I can vouch for the excellence in the quality for both hunting and Polo boots. I have enjoyed many hunting trips in England and love any chance I get to play Polo. I have found my boots are easily a match for even the most expensive and are of course bespoke and made to measure. It’s just they are at a fraction of the cost. Regards

The prices given in the table are those quoted by the manufacturers themselves. Hunting boots certainly don’t come cheap – especially those by Maxwell and Lobb. I had not included RM Williams in the table, being under the impression that they made only Jodhpur boots. Having looked into it a bit more I see they do make hunting boots (and polo boots) – RRP A$1545. Are those the ones you mean?

I’ve been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts in this kind of house . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Studying this info So i’m happy to exhibit that I have a very excellent uncanny feeling I found out exactly what I needed. I such a lot without a doubt will make certain to don?t omit this web site and give it a glance on a relentless basis.

Excellent article. Do you have any recommendations about where to get spurs inserted into

George Boots?

I’m assuming you mean the swan-neck spurs for ceremonial occasions and formal dress for mess? Most George boots are made by Sanders, and I’m sure if you approach them they will be able to help or advise on fitting a spur box. Our article on Sanders may help. Here is their address.

Mr Long, RM Williams make many many different types of shoes. I have indeed recently purchased a beautiful pair of London Tan French Calf Brogues. They are beautiful… Cost $395.00 Australian Dollars completely bespoke. Anyway, AU$1500.00 still seems high. The most I have paid is AU$1200 at full price late last year. Usually you can get them quite a bit cheaper then that. Anyway by the by I understand they are not readily available in other countries. Just be aware I suppose that RM Williams do make some fantastic footwear. Of course I am not going to mention the fashion Chinese made rubbish which knowbody really buys.

Mr Kerr, if you are prepared to forward to me your email address I could put you in touch with a friend of mine who custom makes riding spurs here in Australia. I am not sure your exact specifications you require but we could find out for you. Regards

Dear Kurt, why don’t you share the contact information of your friend right here.

Are you sure we are talking about riding boots from RM Williams? They are not listed on their website and outside of Australia I suppose it is next to impossible to get them bespoke. Also the one’s I found online are listed at USD$1,256.31 not $395. So either you got a fantastic deal or we are not talking about the same thing…

Spurs are still freely available in the UK; however, I believe the type of spur Mr Kerr is interested in is rather unusual in that it attaches to the boot without the use of straps.

The article looks great, thank you .

To all those that require a intergrated spur box in the heel, this is a job that we’d be happy to help with!

regards Emma.

Dear Sir, it would appear , that a company named James Taylor& Son, 4 Paddington Street, W1 was not mentioned in your article.I am a riding novice and not familiar with all aspects of riding. To me even though this company seems to be familiar with producing bespoke(and not just made to measure) boots for dressage, jumping , hunting and Polo.I had shoes made before and I quite like them, therefore I ordered a pair of boots for hacking out. Perhaps it is worth going more into depth while investigating instead of just browsing the web for posh lables. kind regards W. Drapela Austria Europe

Dear Dr. Drapela, while I appreciate the information about James Taylor & Son, I disapprove of your condescending tone. Obviously, this was an article about Horace Batten riding boots, which is not a well known shoemaker. The list was simply a comparison to other more well known makers and by no means an attempt to create a definitive list.

If you tell us what the boots at James Taylor & Son cost and what the delivery time is, we are happy to add them to the list.