Whether you are attending a formal dinner, a cocktail party or hosting an informal dinner, the art of conversation is a skill that can be mastered. People who have will thrive at work events and are likely to climb the career ladder much faster than the ones who don’t. Therefore, we are offering you today a history of the art of conversation, suggestions for self-assessment and tools to learn this important art.

A History of the Art of Conversation

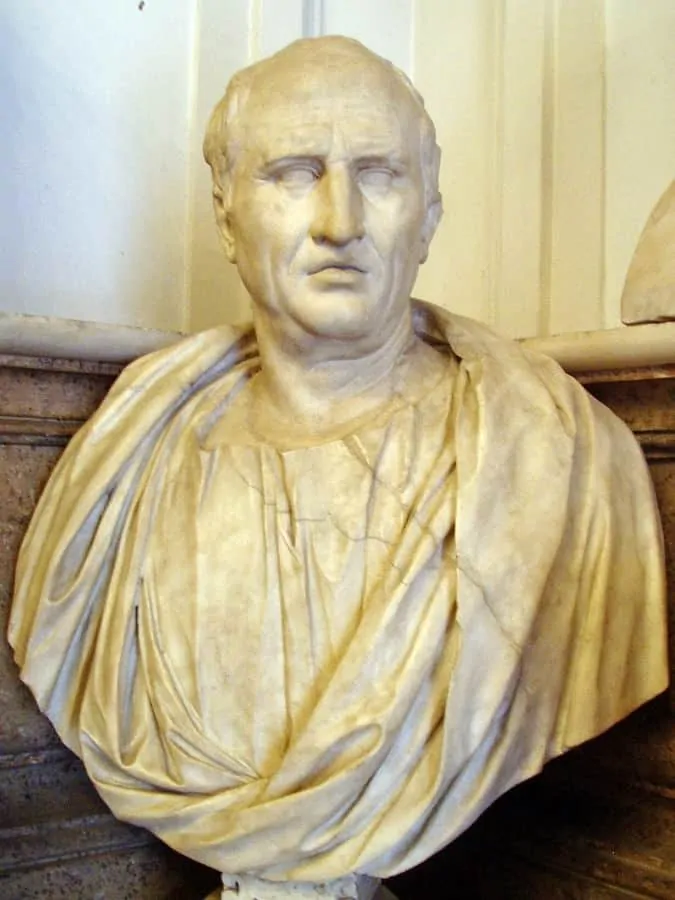

The philosopher Cicero, the French salons and British coffee houses of the 17th and 18th centuries bequeathed to us the structure, rules and expectations of artful conversation. From Cicero we have rules about conduct and content of informal conversations. In de Officiis (On Duty), written in 44 B.C., Cicero codified for the first time rules he believed ought to govern good conversation.

“There are rules for oratory laid down by rhetoricians; there are none for conversation; and yet I do not know why there should not be.”

Cicero profoundly influenced the early Catholic Church. In 390 A.D., St. Ambrose declared de Officiis authorized for Church use, and it became a governing text on moral authority during the Middle Ages.

From the French salons we get rules about how artful conversations progress and which linguistic tools aid in that progression and how those tools can keep us from offending others; and from the British coffee houses we have our notions of the egalitarian nature of informal conversation. In both the French salons and British coffee houses the bourgeois and nobleman alike mingled. In French salons, however, the social hierarchy of the nobility was maintained by allowing commoners to interact with the nobility as long as they followed rules of behavior and conversation.

Basic conversational skills included, among others, politesse (sincere good manners) and enjoument (cheerfulness). As the conversation progressed the skill level grew as well. Humor became important. The deftly delivered bon mot, for example, was expected.

British coffeehouses, by contrast, cared little about stylized conversations. What mattered was a warm, convivial environment where the emerging middle class men (approximately 35-40% of men who could afford the one penny entrance fee) could, along with the upper classes, join in conversation on everything from ending slavery to the emerging stock market. By 1734, there were 551 documented coffee shops in London; if unlicensed facilities were included, the number soared past 1,000 to as high as 8,000. Within the walls of coffee shops, Londoners informal conversation laid the foundations of what would become the stock market, auctioneering and insurance industries. Indeed,“at White’s on St James’s Street, famously depicted by Hogarth, rakes would gamble away entire estates and place bets on how long customers had to live, a practice that would eventually grow into the life insurance industry.”

Communication and Conversation Today

Twitter and Facebook, if you believe cultural doomsayers, means the end of conversation. The hash tag and 140-character limit of Twitter and the endless updates of Facebook create a society where we no longer possess the skills to dwell together in garrulous ease. This attitude reflects a kind of historical myopia. The semaphore and the telegraph, telephone and teletype all communicated information in more direct, less discursive manner than conversation.

Communication has always fulfilled two important, human, goals:

1. the need to share information (“don’t eat that plant!”)

2. the need to talk about hopes and fears, to live amongst one another in ease and intimacy

Communicate derives from the Latin verb communicare and means to share. Conversation comes to us from the Latin conversatio and means to living among, intimacy, familiarity. While both words concern themselves with human language and meaning, conversation has far greater intimate connotations than communication. As early as 1511 conversation meant sexual relations.

It should come as no surprise, then, that when mastering the art of conversation, both communication and conversation are important. Failure to understand the differences between communication and conversation can cause problems. As with all manners, context is important.

What Not To Do

In order to become better conversationalists the first challenge is to discern when we must converse with someone versus simply communicate with them. Where it gets tricky is that communication – often manifest as chit chat or small talk in America and England – is the path through to conversation. There is always a period in a conversation when all can go wrong quickly.

I recall a bumbling fellow American who too quickly rushed to make a joke – and a bad one at that – with a stranger. When this boor learned that his conversational partner was from Wisconsin, he responded, in a voice even louder than before, “Oh! You’re a cheesehead.” The victim hesitated, laughed and said, “yes.” Then he ended the conversation.

Clearly our clod advanced too quickly to humor. He chose to offend (if the ensuing silence of the other man and woman and my cringing were any indication) rather than offer a means of further communicating (in the sense of achieving more intimacy). I’m not suggesting that he needed to move into more intimate territory, either. But instead of cheesehead he might have said, “Oh Wisconsin? How long have you lived there?” or something polite and acceptable within the realm of small talk.

The Importance of Small Talk as Communication

Small talk can be dreadfully boring but it is subject to its own rules. In English is not just social lubricant, as it aims to reinforce our notions of fair play and equality. In cultures where small talk is frowned upon, other social rules will prevail. You must understand the language rituals of the culture you are in to become an artful conversationalist. In cultures where people expect small talk – at a party or work function, even vacation – you can learn to skillfully navigate a dialogue from chit-chat to conversation.

All conversations are a mix of communication and conversation, quick answers and longer stories. Where you are more extroverted than others, you may talk more. In other instances, you may choose to listen rather than talk. There are no rules here. Each interaction is different. And your skill will increase as you learn to interpret other’s body language and facial expressions.

You must practice all the time. More than anything else, if you are generally concerned about your fellow strangers and really believe that we are more alike than different, and let them speak more often, then you are well on your way to mastering the art of conversation.

Also, remember to have fun!

How to Master the Art of Conversation

Self-Assessment

Knowing you need to improve your skills takes you very far to achieving a greater ease in conversation.

1. To instill greater confidence, make a list of your accomplishments and become comfortable talking about them. You need not be a braggart, just someone who believes in himself.

2. To gain greater clarity, ask trusted friends how you appear and act in social situations. How do others react to you? What do you do well? What suggestions for improvement do they have? Ensure to ask for honest feedback. It may be more difficult to listen to or even difficult but it is the only way for you to really improve.

Self-Improvement

Conversational Skills (Cicero Redux)

A review of books and articles on increasing conversational skills is really Cicero, updated. Today we offer some added tools, like telling stories, but the majority of behaviors that reflect the art of conversation come to us through him.

Cicero believed that conversation should be a dialogue (“let him regard alternation as not unfair.”) In informal conversation, Cicero believed:

- A well-mannered person should not be too verbose and should let others speak.

- With regard to subject matter, he should show “due gravity” during serious conversations and lightheartedness during amusing topics.

- A person should never let a conversation reveal character flaws: do not gossip!

- Topics should focus on private affairs, politics and the theory and practice of the arts; when conversation wanders, work to move the conversation back to these topics.

- Don’t talk about subjects not of interest to others.

- Learn how to end conversations tactfully.

- Above all else, never lose your temper or speak in anger.

Be a Great Listener

“I like to listen. I have learned a great deal from listening carefully. Most people never listen.” Ernest Hemingway.

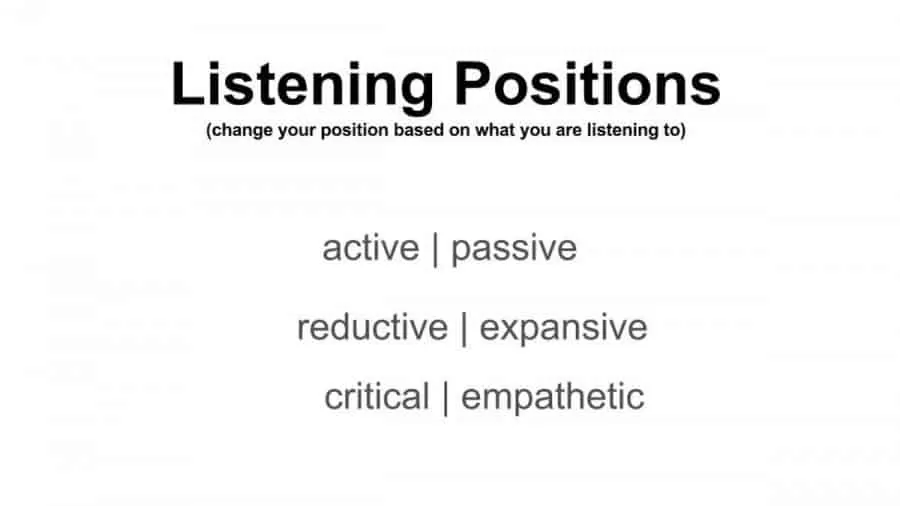

We listen in different ways for different reasons. Julian Treasure describes six different listening positions. Each position allows us to understand and retain different types of information. When we are acting as a great listener, we want to adopt active, expansive and empathetic listening positions.

The Different Type of Listening Positions

- Active – makes others feel heard, using techniques such as reflection and summarizing.

- Passive – non-judgmental, like listening to music.

- Expansive – open to whatever comes (women typically listen with this style.).

- Reductive- selective, discarding whatever’s not on-target for the listener’s goals (men typically listen with this style).

- Critical – has conscious filters in place

- Empathetic – makes others feel emotionally understood

Treasure also suggests using the acronym RASA (sanskrit for juice or essence) when in listening roles.

- Receive (pay attention to the speaker)

- Appreciate (making little noises like “umm” or “okay)

- Summarize (“so what you’re saying is….”)

- Ask (ask questions after the speaker is done talking)

Develop a Sense of Humor

We can’t all be comedians but we can develop our sense of humor. You may never develop the skill of the well-timed bon mot, but you can learn to identify what makes you laugh. Then try inject those observations into your own conversations.

One way to do this is through self-deprecation. The more able you are to turn humor on yourself, the more you will contribute to others’ ease and be well thought of, too. For example, I am bald and rarely miss an opportunity to make some joke at my own expense. This lets people know I don’t take myself too seriously and almost always makes people smile.

Read, Then Read Some More

Christopher Hitchens was considered one of the great conversationalists of our times. He was also known to have read widely and gifted with immense memory recall. While most of us won’t ever exhibit such mastery, we can choose to read a variety of news sites, books and magazines. Pay particular attention to viewpoints different from your own. Take the time to really understand the author’s arguments. You need not agree with someone’s conclusions to understand his or her points. If you can adequately articulate the point of view of someone you don’t agree with in a group setting and do so kindly, you will be known as a great conversationalist.

Don’t Gossip, Ever

I shall repeat Cicero on this point: any inclination to gossip, Cicero believed, betrayed defects in a man’s character.

“[A man] should be on the watch that his conversation shall not betray some defect in his character. This is most likely to occur, when people in jest or in earnest take delight in making malicious and slanderous statements about the absent, on purpose to injure their reputations.”

Never gossip, ever. Even if everyone else is doing so. If those people are gossiping about someone not present, what might they say about you when you’re not around?

If you’re feeling like a conversational ninja you may attempt to redirect the conversation. When there is a pause in the negative conversation – and there always is – you might say something like, “John, when you mentioned the polar vortex a little while ago, can you elaborate on ______?” Even if you know the answer, feign ignorance. The greater goal here is to move the conversation to kinder topics.

Brush Up on Logic

I do advocate discussing all topics, including the American no-no topics of politics, religion and sexuality. Discussing politics or religion is not the problem. The problem is that we no longer teach logic and rhetoric in school. We have lost our ability to argue thoughtfully our positions; lost our ability to question carefully someone about their opinions; and lost our ability to question a person’s arguments without impugning their character.

Learn the fallacies of logic, like the strawman (misrepresenting someone’s argument to make it easier to attack); the appeal to nature (making the argument that because something is ‘natural’ it is therefore valid, justified, inevitable, good, or ideal); and my personal favorite, the fallacy fallacy (Presuming a claim to be necessarily wrong because a fallacy has been committed.). Click here for your very own logical fallacies poster.

By asking thoughtful questions or pointing out people’s logical fallacies, you can keep the conversation focused on ideas rather than people. You will also learn the flaws of logic in your own beliefs and opinions. And remember, the passion a person feels about some issue is no different from your passion. Admire that passion. At least they care enough to not be cynical.

Learn to Ask Deeper Questions

Ask good, open ended questions:

- who was your favorite teacher and why?

- tell me your most profound experience with food?

- what book or books changed you ?

- which song or songs remind you of your youth and why?

For a more in depth discussion about this type of small talk, the following video elaborates on these types of questions:

Learn to Be a Good Storyteller

Great stories don’t happen. A gentleman makes them happen in his imagination. View your life as an adventure. What are you learning? What is happening in the world right now you find fascinating? What are you passionate about?

The Mechanics of a Good Story

- Using sensory words “windswept garden” “lemony scent” activate and will rouse our sensory cortex. When we hear stories we are actively participating with the speaker. What happens to him, happens to us.

- Get to the point quickly. Stick to verbs. When using adjectives choose wisely. Why use small when miniscule is so much more engrossing?

- Make sure your opening and closings are strong. Try to tell the story in the present tense.

- Give one or two pertinent details and only those details.

- If you’re telling a story with controversial material, don’t reveal it right away. Discussing a cousin who is a convicted embezzler or worse? “I had a relative who did something we don’t talk about even today.” Then later, “You all probably know someone or about someone who did the same thing.” Then present the reveal.

- Mimic the action of the story. This works especially well if the story describes someone who gesticulates wildly and so on.

- End on your best point.

Sven Raphael Schneider shares a great story here about selling his beloved Goyard luggage so that he and his new love could afford to see another after he returned to Germany. His story contains many of the elements listed above. Not only is it a story well told, but we learn a few things about Raphael in the process. His personal philosophy about possessions, his business acumen and the great love he felt for his future wife. In learning about him, we also learn about ourselves. Would we be willing to sell such luxury items for love? Can we be sad about an event without regretting it? What does owning luxury items really mean?

With thoughtfulness and practice and a willingness to fail at your efforts (and you will!) mastering the art of conversation is not too hard. I look forward to hearing your stories about favorite conversations, conversational mishaps and more in the comments.

Additional Resources & Books of Interest

The Art of Conversation Board Game – just a few cards but the questions are great and you will learn the things discussed here in a relaxed environment.

The Art of Civilized Conversation: A Guide to Expressing Yourself With Style and Grace

How to Speak So That People Want to Listen Course by Julian Treasure.

Cicero’s de Officiis

Translation 2

Cicero’s Profound Influence

Emily Post’s 1922 version of the art of conversation. We see again Cicero’s profound influence regarding artful conversation.

French Salons

The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment, Dena Goodman

Women and the Public Sphere in the Age of the French Revolution, Joan B. Landis

The History and Meaning of Salons, Benet Davetian

British Coffee Houses

The Coffee-House: A Cultural History, Markman Ellis

The Coffeehouses as sites of social distraction (rather than as I argue promoters of conversation), circa 1673, Tom Standage

Begging your pardon, but I don’t believe the Catholic Church existed in 390 BC. I think you may mean 390 AD.

Of course you are right, I corrected it.

Great content. Loved it. Thanks for putting this up!

You’re welcome! What was the most valuable piece of advice in your opinion?

Great piece, especially the part about logical fallacies. But if you are dealing with someone who has a tendency to rely on them, how would you approach it in conversation without resorting to Ad Hominem, aide from simply removing yourself from the conversation?

I really enjoyed the history as well as the advice that you brought up in the column.

Please keep articles like this coming.

Definitely well written and full of witty advices.

I am a newcomer on your blog and I am really enjoying all the topics.

Vielen vielen dank!

I was always taught the basic structure for conversation with three words – You, We, I. Ask of and listen to the other person, then move it on to common ground and finally talk about yourself – personal anecdotes, life experiences etc. Simple but memorable and hopefully stops overpowering boorishness.

Of course, that won’t work if the other person wants to follow the same order ;)

I found this article extremely valuable and the content definetely covers the subject precisely!