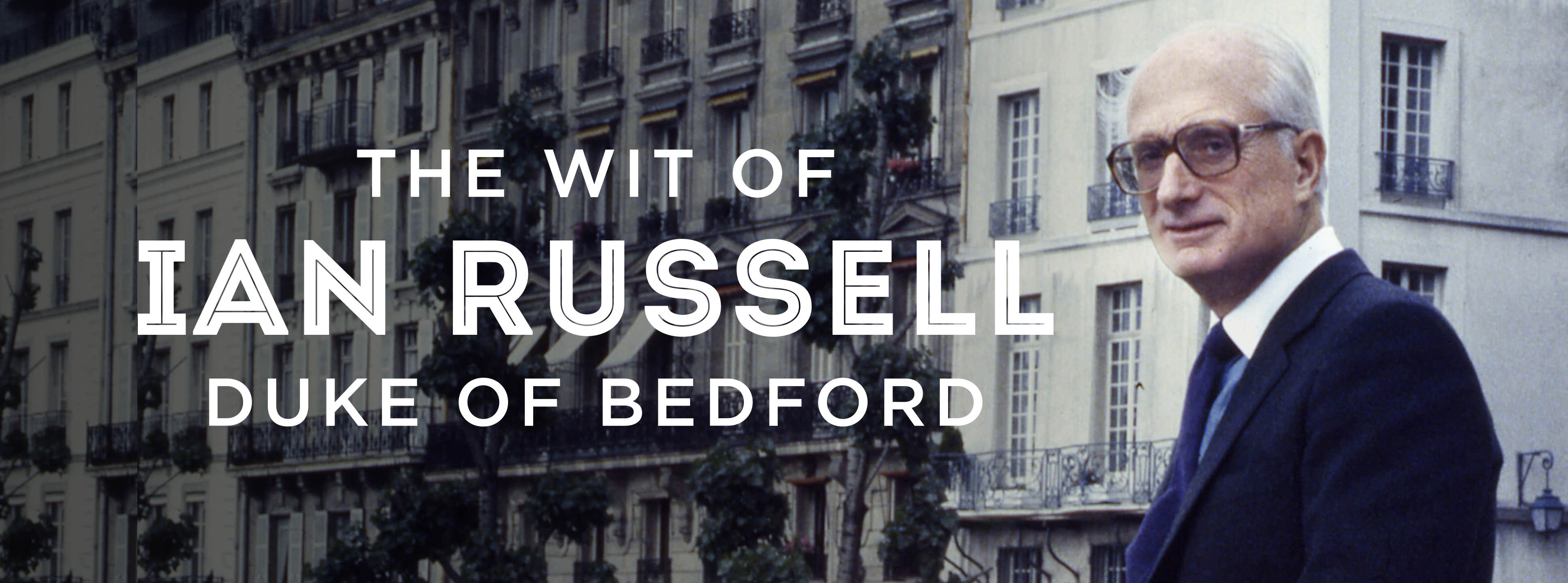

Gentleman’s Gazette has already mentioned Sir Ian Russell here as the author of The Duke of Bedford’s Book of Snobs. But his witty remarks on the British peers of the realm and elegance were not exhausted in that book; he wrote three others, and we’ll try to show our readers some of his best quips and life tips. Meet Ian Russell, the 13th Duke of Bedford.

Ian Russell: Poor Rich Kid

If you think that it is easy to belong to a family who “thought themselves slightly grander than God”, as the Russells did, try to imagine that your dad and your granddad won’t allow you to touch your own share of the fortune because they consider you an irresponsible lad: A year before the 11th Duke died in 1940, Ian Russell’s father Hastings disinherited him because he disapproved of Ian’s – then 22 – marrying a divorcee thirteen years his senior. A penniless Russell then went to work as an estate agent, collecting rents in Stepney.

In his first book – A Silver-Plated Spoon (1959) – he pours his memoirs and reproduces some letters exchanged between him and his father, showing the bitterness inside the familiar network.

A High-Flying, Eccentric Family

His family was, well, peculiar. His grandmother – Mary Russell, Duchess of Bedford – was an ornithologist and aviator, a late-life practice that made her known as The Flying Duchess. This, by the way, was the title of Ian Russell’s third book, published in 1968, where he outlines a picture of his mother. During the 1930s, she broke many long-distance flight records with her single-engined Fokker F.VII, “The Spider.”

However, in 1937, she left Woburn Abbey in a DH.60GIII Moth Major and crashed into the North Sea; her body was never found.

Ian’s father, Hastings Russell, was a naturalist and an ornithologist, an interest he shared with his mother: He bred two lorikeet species, recognized as the world’s first breedings in captivity. He had a pet spider, which he regularly fed with roast beef and Yorkshire pudding; Hastings, on the other hand, was a vegetarian. Austere, he didn’t smoke, drink or gamble, and was even sued by his wife for “restoration of conjugal rights”, who portrayed him as “the most cold, mean and conceited person” she ever met.

Woburn Abbey, the Family Seat

The fans of TV series such as Downton Abbey are able to see how life must have been in the homes of dukes and bearers of lesser titles that compose the peerage of the British Empire.

Obviously, the cost of keeping such fabulous residences, some verging on (or exceeding) the size of palaces, is not small, as this article in The Telegraph shows. Also, the large household staff started to dwindle after WW I, for financial and lodging reasons. For all this, something around 1,200 country houses were demolished in the 20th century.

But not Woburn Abbey. A gift from Henry VIII (actually, he took it in 1547 from the Cistercian Abbotts) to John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford, it became the seat of the Dukes of Bedford. It was a marvelous residence: John Adams, the future second President of the United States, visited some homes in that area and noted in his diary that “Stowe, Hagley, and Blenheim are superb; Woburn… beautiful.”

One of its occupants, the 7th Duchess, Anna Maria Russell (1783-1857), became famous for the invention of the afternoon tea in the mid-1840s: she favored Darjeeling tea, cakes, and sandwiches to fill in the gap between lunch and dinner, which was served late.

The Stately Home

Our portrayed gentleman of style received Woburn in 1953 after the death of his father and faced the heavy inheritance duties. Besides, the mansion was half-demolished, half-derelict. Not a man to quit easily, the Duke of Bedford kept the ownership instead of handing the estate to the National Trust and, in 1955, opened it to the public for the first time.

In 1970, he added Woburn Safari Park as an attraction, with great success. Asked about the unfavorable comments from his peers after he turned the manor into a visitor’s spot, he said, “I do not relish the scorn of the peerage, but it is better to be looked down on than overlooked.”

He was not the first peer in the business of stately homes, an expression that has been used to indicate a country house that opens to visitors at least some of the time: its pioneer was Henry Thynne, 6th Marquess of Bath (1905-1992) and its Longleat. In 1947, also due to inheritance duties, he opened the house to the public, adding a safari park in 1966.

But Ian Russell elevated the stately home business to an art, to the point of writing a book on it: his fourth and last book is How to Run a Stately Home, published in 1971. The Duke was a keen observer of human behavior and a peculiar sense of humor, but the book is useful for anyone who wants to do as he did and receive visitors – and who knows how many of his once scornful peers have read the book and followed his advice…

Here is a tongue-in-cheek remark from Russell on the importance of comfort stations, for instance:

“Very well, you may say impatiently; your advice has sunk in. Loos are important. All right, they are most important. But do you mean to say that nothing else really matters?

“No, I do not. While loos must come first, they would not take you far without teas and car-parks. A Stately Home with excellent loos, good teas served at a reasonable price, and sufficient car-parks (near the loos and the tea-rooms) will prosper. If you provide these three commodities, then – according to my computer – 87.3 per cent of your visitors will not notice if you have no house at all.”

An Original Dresser

It is noteworthy to say that the 13th Duke of Bedford was inducted into the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1985, a list that includes, among other well-known names, Gianni Agnelli, Giorgio Armani, Fred Astaire, Pierre Cardin, and Lapo Elkann.

However, it must be said that being a Duke does not grant you a good fashion sense, as this picture of the Duke of Marlborough shows.

Ian Russell’s view on one’s image helps to explain why he cared so much about dressing well: “never mind the essence, it is only the appearance that matters.” A clear and deliberate contrast with his father, perhaps, with the latter’s almost spartan and ascetic lifestyle?

I believe so: according to Design at Home: Domestic Advice Books in Britain and the USA Since 1945, a book by Grace Lees Maffei, the Duke “commoditized his life. He appeared on television, allowed a nudist camp in his grounds, hired himself as a dinner companion and raffled the services of his butler, James Boyd, as a prize in an American competition”. By the way, we must surmise that the poor winner of Mr. Boyd’s services could not enjoy them properly, for the guy’s house “was invaded by so many camera-men and newspaper reporters… that he was unable to carry on his normal duties”.

The Duke’s Style

Suits

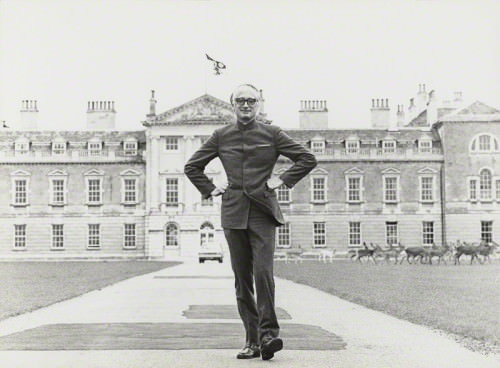

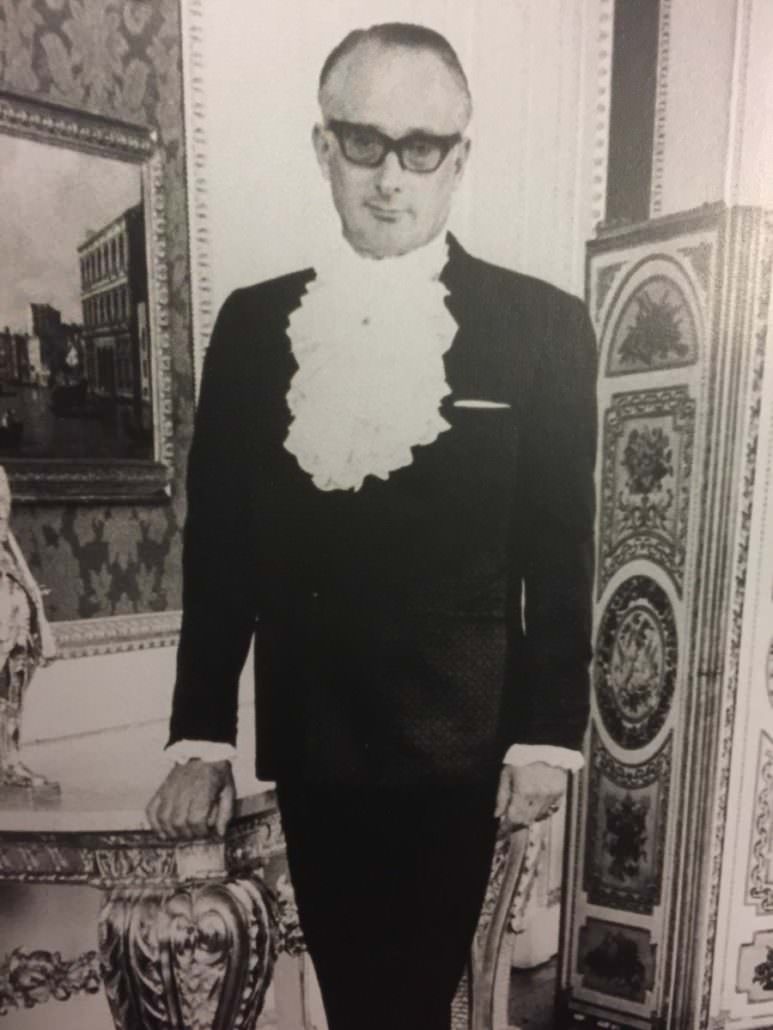

Here he dons a Mao suit in front of Woburn Abbey.

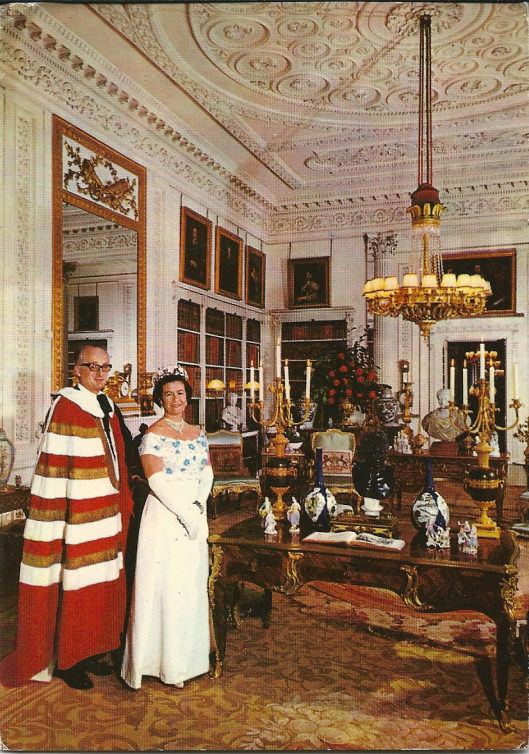

The same suit is worn indoors, in the company of his third wife, Nicole.

He could also be conservative, as this picture above shows.

Suits “must be made to measure“, he said. “Ready-made suits will not help you in the snobocratic world”. He was strict about colors: “dark grey, navy blue, and black are the only possible colors for a man’s suit… Do not go in for green suits and as for brown, it is fatal. You will be the ‘type of man who wears brown suits”. (Personally, I disagree about black suits, but we’re talking about the Duke of Bedford’s opinion.)

Your clothes, he quipped, “will never be too fashionable, they will never follow the latest craze, but their quality and cut will tell even after many years. Clothes should be obviously good but they must not scream: ‘Look at me, how elegant I am!’ The wearer’s personality should always be stronger than his clothes”.

On one of his peers, he commented that “the… [15th] Duke of Norfolk always wore appalling clothes. They were old and comfortable, and he liked them. Members of his family kept telling him that he just couldn’t go about dressed like that. ‘Why not?’ the Duke retorted. ‘No one knows me in London. And everybody knows me here – so what does it matter?'”

In this picture, for instance, we see the Duke wearing Turnbull & Asser’s Clarney shirt in 1966, with ruffles instead of the permanent ascot of the Brook Brothers’ version, in a flagrant contradiction to one of his own rules: “You should be just one or two steps behind the latest fashion – but no more. Frilly evening shirts should not even be looked at.”

One of his funniest moments shows as a quip on sheepskin coats: “I should hesitate to pronounce a firm verdict. They are both in and out, I should say. But if this delphic pronouncement is deemed a shade ambiguous, I would say – with a hardly audible sigh – all right, go on wearing them. I have always been a tolerant sort of fellow.”

Accessories

His sense of humor comes through in remarks such as this one about handkerchiefs: “These popular and necessary articles should be kept in the pocket and not – I repeat: not – in the sleeves of your jacket.” And on knitted items: “Generally speaking, anything knitted by daughters and nieces at school, while they may be touching, are not to be touched.”

On ties, he favored some color, thinking that “they are excessively dull and quiet in Britain.” He thought that details, such as socks, were the secret of a well-dressed man: “Even if a man is not greatly interested in clothing, he should pay some attention to his socks. It is no good leaving the buying of socks to your wife or a retired nanny, nor it is right to wear the socks which these charming and thoughtful ladies might knit for you”.

Hair

A good haircut, he thought, was essential for a proper image. “When Britons emerge from the hairdressers… they look like the victims of practical jokes”. Thus, completed him, “choose a barber who – rare specimen though he may be – knows a bit about cutting hair.” On facial hair, his advice is to avoid it, or be discrete: “Moustaches with double twists… mustaches which disappear behind your neck and come out again on the other side, should be avoided. Do not turn your face into a joke. If you cannot make other and better jokes, leave the humor to others.”

Conclusion

He finishes his book with some remarks on climbing the social scale: “Being an upstart is, perhaps, natural to many human beings. Being a down start is much rarer; but also much wiser.”

Though the Duke certainly achieved notoriety by virtue of his title and fortune as an English peer, his wit and style make him a notable character of the modern world of a gentleman.

His Grace, Marlborough appears to wear an ‘out of prison suit’ residual in some secret 1930’s Wormwood Scruggs storeroom. He apparently needs either Heimlich application or additional resident drug withdrawal. His Grace, Bedford is wearing a Nehru jacket which one supposes is atonement for Britain’s colonial legacy. If that is in fact some version of Mao’s togs, it is interesting to reflect that Mao’s cultural revolution would have made short work of the duke. The best he could hope for would be decades of reeducation (i.e. hard labor leading to death) on a pig farm. No one known to have worn a clarney shirt ought to pronounce on style – EVER. It is hideous ruffles exploding from his chest like an alien reptile lusting after Sigourney Weaver. He seems now to have modified his dress to something approaching restrained elegance.