Richard Wagner is one of the most controversial composers in history – and this is genuine controversy. He is not controversial in the way some rock star engages in promiscuity or drug use. He is not a common thug who happens to be a musician. Beginning as something of a political radical, Wagner eventually became heavily associated with anti-semitism and Nazis, and the connection is stronger than you may suppose.

Wagner, as well as having a strong career as a composer and theatre director, was a noted polemicist, and it is from his writings that the darker elements of his personality and ideas come through. Some are revolutionary, leading to a change in music and performance that impacts to this day. Others are so reactionary and hateful that they muster contempt from those of moral constitution and praise from those who are morally contemptible.

Wagner’s Early life and Operas

Born in Leipzig on 22 May 1813 to a police clerk and a baker’s daughter. Wagner’s biological father died when he was six months old and his mother eventually started a relationship with Ludwig Geyer, an actor and playwright. Wagner came to share his step-father’s love of the theatre, and his early studies feature both music and drama. He was taught basic piano education from his Latin teacher at Pastor Wetzel’s school near Dresden. He had trouble with technical exercises although had demonstrated strong aural abilities, playing theatre overtures by ear.

Around age 9 he desired to become a playwright and his first recorded work Leubald (Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis 1) was created featuring Shakespearean and Goethe influences. He then decided to set the piece to music, requesting his family to allow music lessons. Interestingly, no music for the piece exists, although the play itself is intact.

His proper musical education began in 1828, was well as his introduction to Beethoven (in particular the 7th and 9th Symphonies) and Mozart’s requiem, resulting in his first piano sonatas and orchestral overtures.

In 1831 he enrolled at Leipzig University and studied under Theodor Weinlig, who refused payment due to Wagner’s impressive musical ability. His op 1, the Piano Sonata in B-Flat Major, was dedicated to Weinlig.

Wagner gained the post as choir master at a theatre in Würzburg, Bavaria and at age 20 composed his first opera, the Weber inspired Die Feen (The Fairies) although the piece would first be performed in 1883 after Wagner’s death. He returned to Leipzig the following year working as musical director at the Magdeburg opera house, eventually staging his first opera Das Liebesverbot (The Ban of Love) based on Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure in 1836. This was however the beginning of a dark period for Wagner. The piece was closed before the second performance and the theatre company that employed him collapsed leaving Wagner with serious financial issues. He did however meet with, the actress Christine Wilhelmine “Minna” Planer, the leading lady at the Magdeburg opera house, who would help Wagner gain employment at the theatre in Königsberg where they found themselves after their marriage in late 1836. Marital bliss was short lived, as Minna left Wagner for another man the following year. Wagner then became affiliated with Minna’s sister Amalie only to reunite with Minna in 1838. Debt was their reunion gift and they fled to Riga in 1839 to avoid creditors. This marked yet another consistency in Wagner’s life: debt.

In September, after a brief stint in London, the couple found themselves in Paris where they stayed until 1842. Wagner earned a minimal amount of money writing articles and arranging other composer’s operas in between completing Rienzi and Der fliegende Holländer )The Flying Dutchman). With the aid of Giacomo Meyerbeer Rienzi was performed by the Dresden Court Theatre, providing Wagner a return to Germany as well as his first true success. He remained in Dresden for six years staging Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser, and mixed with artistic circles in Dresden.

Somewhat at odds with the reaction politics with which he is asscociated today, Wagner was heavily involved with socialist German nationals, associating with the likes of August Rockel and Mikhail Bakunin. He played a minor role in the May Uprising in Dresden, and following its failure Wagner and other revolutionaries were either arrested or fled. Wagner first stopped at Paris and eventually settled in Zurich for his 12-year exile from Germany.

Gesamtkunstwerk – The Total Artwork

Wagner’s time in exile created a great deal of personal trouble for the artist. He was removed from the artistic community he had become a part of in Germany, and although he was able to negotiate the première of his latest opera, Lohengrin, in Weimar in 1850 with his friend Franz Liszt, he had no stable source of income.

However his exile allowed him to further develop and set out his artistic ideas in a series of essays. The two most important of these were his “Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft” (“The Artwork of the Future”) and “Oper und Drama” (“Opera and Drama”). In these he outlined his concept of Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) that synthesized music, dance, poetry, visual art, stagecraft, and drama. In “Artwork” Wagner outline’s his belief that man, or rather the collective of men who feel a common and collective want’ produce art to fill that want’. However, in his view this does become strayed, often by outsiders who simply want to create luxury, which many interpret as his slight towards Grand Opera. The Volk, his term for the collection of men who create true art in response to a want, will create the artwork of the future, which had three primary elements: dance, music and poetry, calling to mind the original ideas behind opera shared with the ancient Greek drama. This artwork will be lead by the artist of the future who “without a doubt” be “the Poet” that would lead a fellowship of all artists.” Ernest Newman sees this concept of fellowship as a pre-thought to the Bayreuth Festival.

“Opera and Drama”, a mammoth “book length” essay, published the following year. Beginning with an extended attack on contemporary opera, including on Meyerbeer whom aided Wagner in staging …, the text then leads to an extended discussion by Wagner of the role of poetry in a music drama. In the final section Wagner provides the overview of his ideal “music drama” as he wished to call them, highlighting the integration of the various artistic forms.

Wagner also published “Eine Mittheilung an meine Freunde” (“A Communication to My Friends”) the same year, and although it does not discuss his philosophy on art, it does act as a manifesto for his future plans. He asserts he will “never write an Opera” again and that not wishing “to invent an arbitrary title for my works, I will call them Dramas…”. He then outlines the structure of the “Der Ring des Nibelungen” (Ring Cycle), which consists of three sections with a “lengthy Prelude”, to be stage at a future festival over the course of three days and an evening.

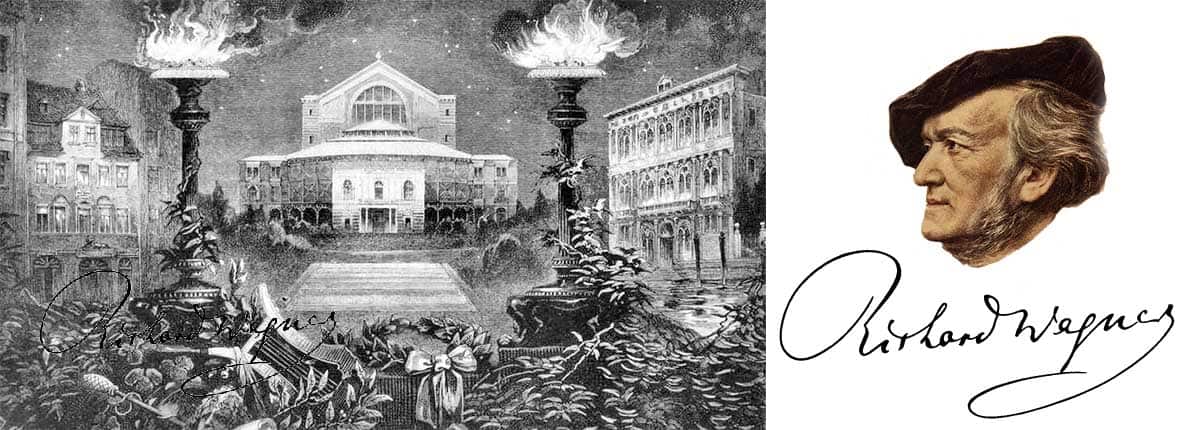

It would be another 26 years before it was completed and performed. And it would have been unlikely for Wagner to ever have produced these works were it not for one man, Prince Ludwig of Bavaria. The young king came to the thrown at the age 18 and was deeply in love with Wagner’s works. Ludwig called for him and within a short period of time Wagner literally had the finances of a king at his disposal. A testament to his new found good fortune was that he was not only able to stage these incredibly ambitious works, but that he would gain control over ever element of the process, which included building a theatre play house to his exact specifications. Thus the Bayreuth Festspielhaus was created.

Der Ring des Nibelungen as the crowning achievement of this approach.

Musical Poetry

Although Wagner wrote extensively about the music drama and even though he did create one of, if not the most ambitious piece of music ever with the Ring Cycle, is contributions to the future of music were less teleological.

Conducting, leitmotif’s, etc.

His greatest contribution was his stretching of tonality to what would eventually prove to be its limits. Major-Minor tonality works on the basic principal of establishing a tonic key (lets for example say C Major), moving away from that towards its dominant key (G Major) that creates dissonance or tension and a desire to return to the tonic key once more, resolving the dissonance. This generally occurs over the course of a work or movement, as in the case of sonata form where the first and last section are in the tonic key with the middle being centered around the dominant. However, there are other ways of introducing dissonance into a work, which is in adding other harmonies in between the progression, extending the dissonance and creating false resolutions that leave the listener desiring the tonic even more. A way of extending this even further is the use of chromatic notes, notes that do not belong in either key, further developing this instability created by the dissonance.

This laid the groundwork for Wagner who with his Tristan chord and over the course of the opera keeps the audience on the edge of their seats waiting for the resolution that refuses to come until the very end of the work.

Tristan Chord, is the starting point of Modernism in music or whether, as Debussy said, it was a beautiful sunset mistaken for a dawn.”

Anti-Semitism

Although Wagner’s career began to show considerable promise, it was during his period in exile that two of his most notable fruit grew: the gloriously rich notion of the total artwork and the bad fruit of his anti-Semitism.

His anti-Semitism is a difficult topic to discuss. Not something everyone wants to talk about but an essential topic on any discussion of Wagner. What makes it a topic of discussion is that these were not privately held views expressed to friends in letters, but were publicly expressed in his polemic writings.

The first sign of his anti-Semitism came with the now infamous essay “Das Judenthum in der Musik“. A great deal of recent scholarship has lead to suggestions that although Wagner was anti-Semitic, the real driving force behind these more public gestures was his second wife and daughter of Franz Liszt, Cosima Wagner. One strong indication of this is that it was after Wagner’s death, when Cosima took over direction of the Bayreuth Festival from 1886 to 1907, that the performance began to take on the anti-Semitic and racial superiority tones that drew criticism of Wagner’s work as Anti-semitic. Author and critic Philip Hensher argues that “under the guidance of her repulsive racial-theorist son-in-law … Cosima tried to turn Bayreuth into a centre for the cult of German purity.” And that “By the time she died, Wagner’s reputation was … at the forefront of a terrible political dynamism: antique stagings of his works were presented to audiences of Brownshirts”.

Another is the fact is that one of the other main texts by Wagner that make strong anti-Semitic tones, an essay called “Know Thyself” that mocked the notion of Jewish assimilation, was, as argued by Oliver Hilmes, encouraged by Cosima.

This does not alleviate the guilt, nor whitewash the anti-Semitic qualities of some of his polemics or the representation of some of his characters. It likewise does not justify his opinions simply as “products of his time.” Liszt, for example, both a friend of Wagner and Cosima’s father, was highly embarrassed at the publication of his “Das Judenthum in der Musik”, realizing even in the same time period the foolishness of such ideas. It is a tarnish on his reputation that Wagner must wear.

However, the fact that this has been argued for so long, the fact that it matters, is testament to power and revolutionary nature of Wagner’s work. If he was a musical hack who had these views he would be forgotten and his catalogue would decay over time like the pages that hold his contemptible views. But because he was such a visionary artist, and because his works are so magnificent, we as listeners struggle with these views.

I now encourage you to listen to his music and to reach your own conclusions.

Wagner & Me

In 2010, Stephen Fry, a Wagner music lover with Jewish Roots, made an interesting film about Wagner that you definitely want so see: Wagner & Me

Wagner has also been subject to many documentaries, TV series and films. Youtube has a short documentary and a 5 part documentary about him and his music. See Part I here:

Works Cited & Links:

Philip Hensher, (1 May 2010) Cosima Wagner: The Lady of Bayreuth: Review. The Telegraph Online.

Hilmes, Oliver (2011). Cosima Wagner: The Lady of Bayreuth. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Ernest Newman, The Life of Richard Wagner: Volume II, 1848-1860, Cambridge, 1976

Can only thank you for this superb description of the great composer, Wagner.

Details of his life never known before, at least to me, are very much surprinsing.

What a pleasure must have been knowing personally this music master and discover his real feelings and thoughts to create such beautiful music whilst keeping in his heart such hate for semits.

What a great issue, congratulations !

Thank you for this article. I too am drawn to Wagner’s works, but as I am Semitic by blood, I have struggled with even listening to them.

-Evan

I admire and respect Stephen Fry’s advice on Wagner – That he (Fry) would never surrender the enjoyment of Wagner’s music to the evil that was Hitler.

Simplesmente brilhante

Great enjoyable article. I was not aware of his political involvements during 1840’s although his views on the anti-Semitics are well known.

Nevertheless his compositions are astounding.

Excellent article. Well done. Keep it up !

I just watched a fascinating DVD titled, “Wagner and Me”. The British actor, Stephen Fry, (Gosford Park, Le Divorce) visits Bayreuth and other locales frequented by the great composer. Fry, who is Jewish, eruditely and humorously discusses Wagner’s well known, but little understood hatred of the Jews and their culture, as well as how the Nazis integrated Wagner’s music into their ghastly agenda for world domination. Regardless of this deplorable episode of history, the music remains the greatest the world has yet heard