I’ve long been intrigued by the contradictions inherent in the Victorian cummerbund. First there’s the seeming paradox of the original garment’s use to ward off chills in the tropics. Then there’s the contrast of an informal sash being worn with a full-dress rig. So it was time to once again turn to online newspaper archives for a more complete picture.

As explained in The Black Tie Guide’s Vintage Waistcoat and Cummerbund section, the garment originated in India and Persia to provide protection from sudden drops in temperature. My recent research has uncovered the physiology behind this function courtesy of an 1878 newspaper report. Because (a) the temperature of the body is regulated by the circulation of the blood, (b) a great proportion of the blood circulates in the intestines, and (c) the intestines are separated from the external air only by thin abdominal walls, the body’s temperature is significantly affected by the air temperature around the waist. Therefore, just as a person in a cold bed tends to curl up their legs over their belly to keep warm, layering fabric around the waist keeps the intestines warm when tropical temperatures drop in the evening. (Who knew that such an innocuous accessory had such a clinical background.)

Europeans trading in India in the 17th century discovered this handy aid and adopted it for themselves. Reports from late 19th century newspapers state that English military officers wore red silk versions to match the scarlet shell jackets of their mess uniforms while civilians wore black silk. Or at least some of them did: One paper indicated that cummerbunds were openly donned “only by domestic servants, peons and irregular troops” along with European tradesmen. Proper Anglo-Indians preferred Saville Row garments, thank you very much.

Eventually, European expats decided to bring the accessory home with them. The earliest reference I’ve found to the cummerbund in Europe is in A History of Men’s Fashion which quotes the June 1873 issue of L’Elegance pratique, a French tailoring magazine. “Need we point out” sniffs the author, “that it is thoroughly bad taste to replace a [evening] vest with the wide belt that constitutes yet another grotesque fashion whose slovenly appearance hardly requires mention? It has been implanted by a few young people, and we would not be surprised if it originated with foreigners.”

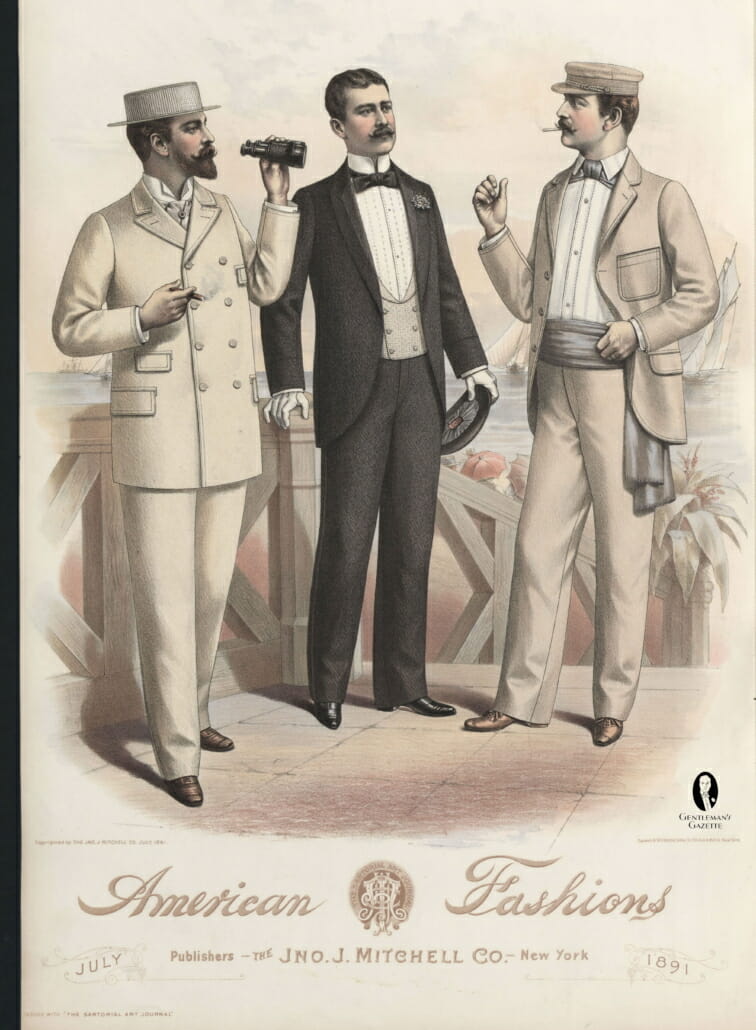

Reports from Anglo-American sources paint a different picture of the cummerbund’s arrival in the West, stating that its initial purpose was a cool daytime substitute for the then mandatory waistcoat. An 1892 US newspaper reported that the Prince of Wales first imported the garment to England following his visit to India in 1875-1876 and prior to that it was unknown to the European upper classes. The Prince’s original intention was that it be utilized as “an article of yachting and smoking apparel.”

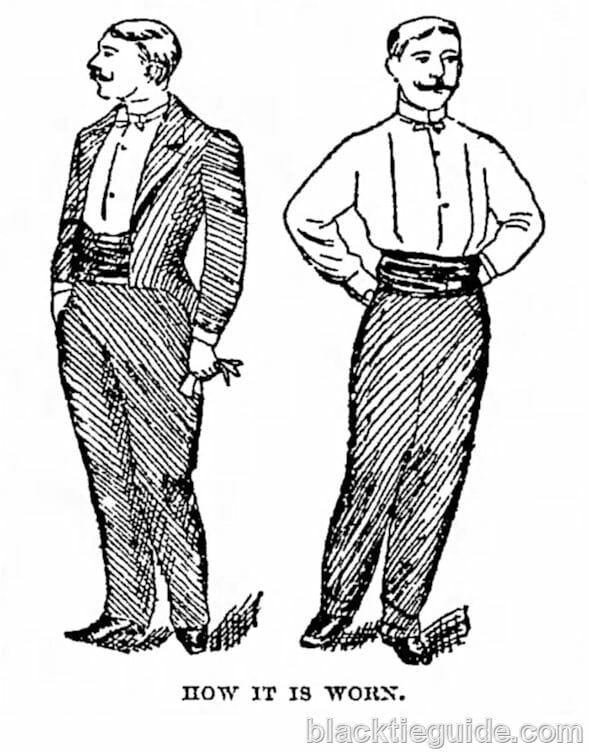

It was then not long before the cummerbund infiltrated evening attire. By 1888 a Michigan newspaper was reporting that tailors were attempting to distinguish their dress suits from increasingly high-quality ready-to-wear versions by inventing custom accents. Included among these was “a new idea some pioneer has recently brought out”:

He proposes to do away with the waistcoat of the dress suit entirely, substituting therefor a sash, or “Kummerbund,” of black silk, which encircles the waist like a bandage. One picture shows the figure without the coat, displaying the real character of the device, which, when partly covered by the coat, presents what at a little distance may be mistaken for a silk vest. Its practical recommendation is more comfort in warm weather, but its chief recommendation is novelty. This sash is to be brought out for a run this summer at the fashionable hotels.

The following year a letter published in the New York World argued that the formal innovation was actually much more practical than novel:

In these hot, sweltering days, when the starched linen collars and cuffs and shirts give place to the comfortable silk and flannel shirts, and the vest is discarded, something is needed to take the place of the latter. Nothing so dressy and neat can be compared to the cool folds of soft silk around the waist. It hides the unsightly band of the trousers with its array of buttons, and gives every advantage a vest affords without that article’s increasing heat.

One of the first references to the color of this formal alternative is from an 1889 English source that reported “the boldest thing in evening dress is the abolition of the dress waistcoat. Instead, a crimson or black silk sash is wrapped four times round the waist.”

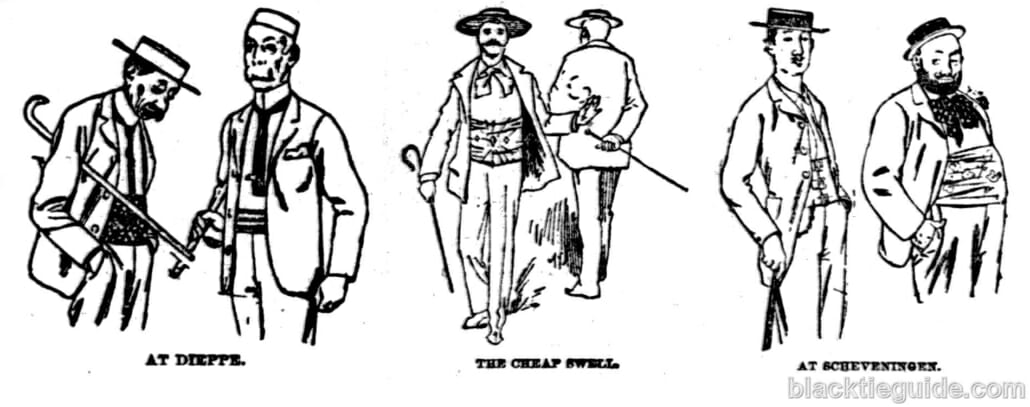

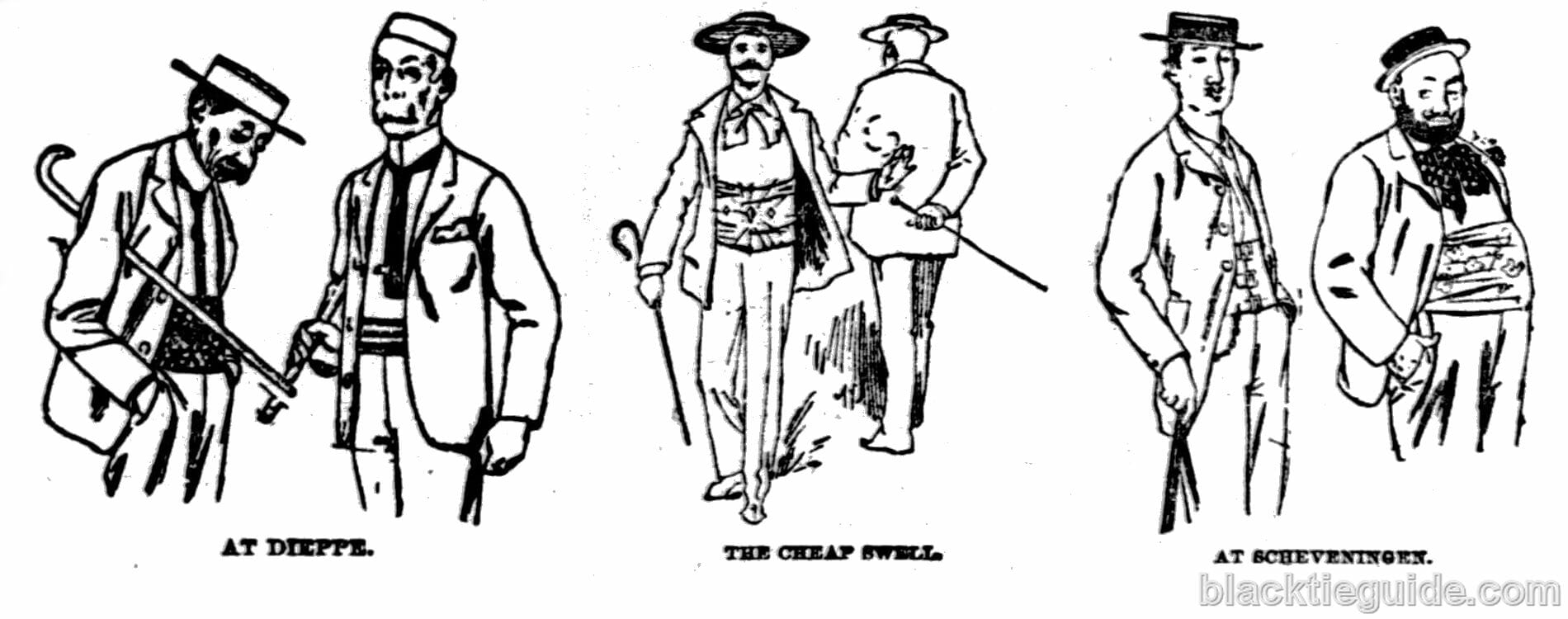

In 1892 the Wichita Daily Eagle gave an extensive account of how the general use of cummerbunds in Europe “has degenerated into abuse . . . they have become deplorably vulgar and have long since been abandoned by the Prince of Wales.” Examples of such Old World extravagance included “soft pink, pale blue or lettuce green surah” fastened with a broaches. Less gaudy, “and consequently less objectionable,” was the yachting version (“dark navy blue grosgrain silk fastened with a huge gold anchor”), the tennis style (“orange and purple striped satin, fastened with buckles of cloisonné enamel”) and the boating interpretation (“green and white striped satin, which being five yards long, has to be wound round and round the body of the wearer by an assistant”). Evening versions, worn with “dress jackets”, were seen in “dark material profusely decorated with raised gold and silver embroidery, seed pearls, turquoise and bits of lapis lazuli.”

The article warned Americans to stick to the simple black or red preferred by well-bred Englishmen in British India. It also cautioned that readers would “do well to bear in mind that it requires a good and elegant figure to look well in any cummerbunds, which present a grotesque appearance when worn by a fat man.”

Back in London the fad gained a huge boost in popularity in 1893 due to a particularly hot summer that year. In the context of of evening wear, a New Zealand paper reported that in London some men were wearing versions that resembled more of a belt than a wrap: “It is a sash of thick, soft black silk, with pockets like those near the waist in an evening waistcoat. It is kept up by bretelles [decorated suspenders] passing over the shoulders, and is expected to ‘catch on’.”

That same year the British trade publication Cutter and Tailor reported that the waistband had progressed into the final frontier of morning dress where dandies prefered “coloured silk bands which appear to be wound twice round the body and then fastened to the side with jewelled or ornamental buttons.”

In 1895 the English evening version was described as being made of silk or colored twilled drill (a hardy cotton fabric most often used for khaki clothing). It was also reported to have become “hopelessly vulgarized” which would explain its fall from fashion by the turn of the century. Although it would re-emerge a few decades later it would be in conjunction with the less formal dinner jacket. Never again would it be considered acceptable with the regal tailcoat.

Sartorial researchers studying the history of this peculiar garment should note that its spelling varied widely up until World War II. In addition to the original Hindustani/Persian kamar-band spelling it also appeared as kamarbund, kummerbund, kummerband (the German word for cummerbund) and cummerband. In fact, the last spelling is still used to this day by some British retailers.

For more details about classic black tie cummerbunds take a look here and you can buy quality black silk cummerbund here.

Also note that the accessory was adapted into women’s wear soon after its adoption by civilian men, becoming particularly popular in the 1950s.

Another great post! Kudos!

Interesting.

You sometimes see conductors wearing a white cummerbund with a tailcoat. Is this considered acceptable within the conventions of white tie for conductors (because of the physical exertions some of them put themselves through) or just an oddity based on ignorance?

There’s no special exemption for conductors. They have been conducting with waistcoats for centuries.

Sashes were worn by European armies from at least the mid 1600s to identify allegiance and later rank. For example, during the English Civil War the Royalists wore red sashes while Parliament wore orange. From the 1700s European officers and sometimes sergeants wore sashes. In the British army the officers wore crimson and sergeants red. Italian officers wore Savoy blue. So, the sash was not unknown before the 1800s and its history may explain why Britons prefer crimson or black.

P.S. British crimson is a deep red wine color. The other crimson is Polish crimson, which is almost like a saturated hot pink. That color was not worn by British or American armies.

As the Groom, I plan on wearing a midnight blue tuxedo with black shawl combining it with a black cummerband, bow tie, and suspenders. Can these accessories all be black? I also plan on wearing black trousers instead of the midnight blue. Is this acceptable? Finally what if I want to take my jacket off towards the end of the ceremony when dancing etc…do I have to remove my cummerband and suspenders? Or can one of both stay on? Thanks!

As The Black Tie Guide explains, having the cummerbund and bow tie match the jacket’s collar is the norm. Having jacket and trousers in different colours is a little unorthodox but a faux pas as both colours are correct. Suspenders are to hold your pants up and never meant to be seen so they can be any colour you wish. As for taking off your jacket, at that point all bets are off as you are no longer following traditional formalwear protocol. Not sure why you would want to lose the suspenders though – presumably you’ll still want your pants to stay up at your hips not down around your ankles.

Hello. I realize the last post on this site was 2916 but thought I’d try my luck. I have come across an old Victorian leather top hat case. Inside the case is another box with a cummerbund. The back side says The Bendix Buckingham with a lion head on a crown. I can’t fiind any info on this name.

Also, the top hat reads Collins & Fairbanks , Boston

The case reads A&NCSL 105 Victoria St Westminster SW. Army & Navy co-operative society. Limited. Made at the society’s works.

Any guidance would be appreciated! Thank you, Kim

PS this belonged to my great grandparents.