Tailcoat Cut: Strictures of Body, Sleeves, Skirt, Lapels, et al.

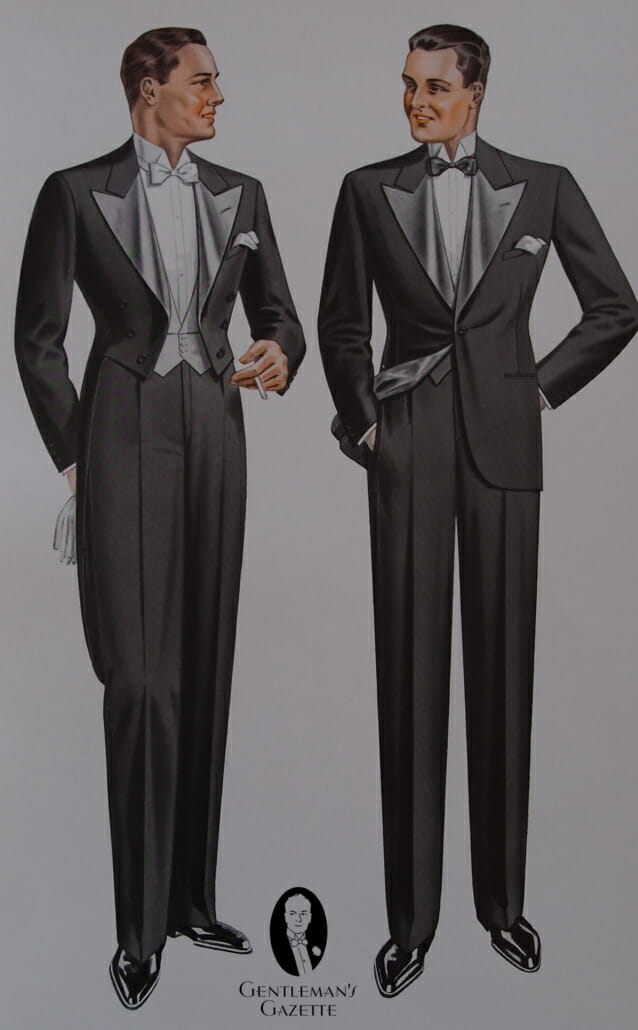

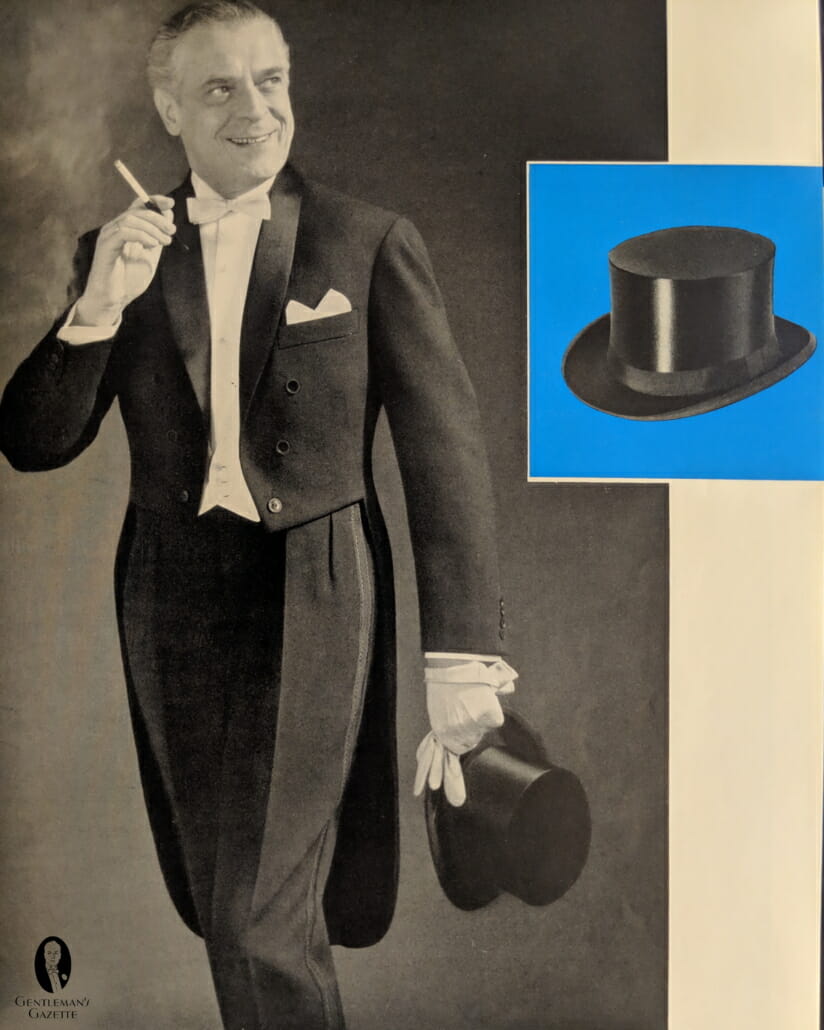

What North Americans refer to simply as a tailcoat is correctly called an evening tailcoat or dress coat to differentiate it from the formal day tailcoat. The coats differ in that the evening coat is a (pseudo) double-breasted model with a sharply cut-away skirt and silk-faced lapels while the morning coat (or cutaway in American English) is a single-breasted model, has a skirt that tapers away gradually and carries self-faced lapels.

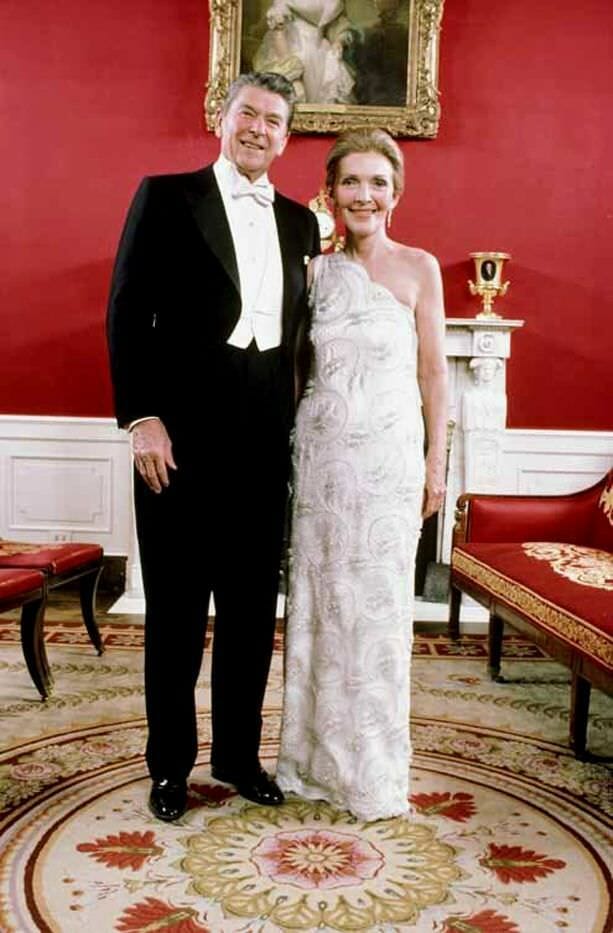

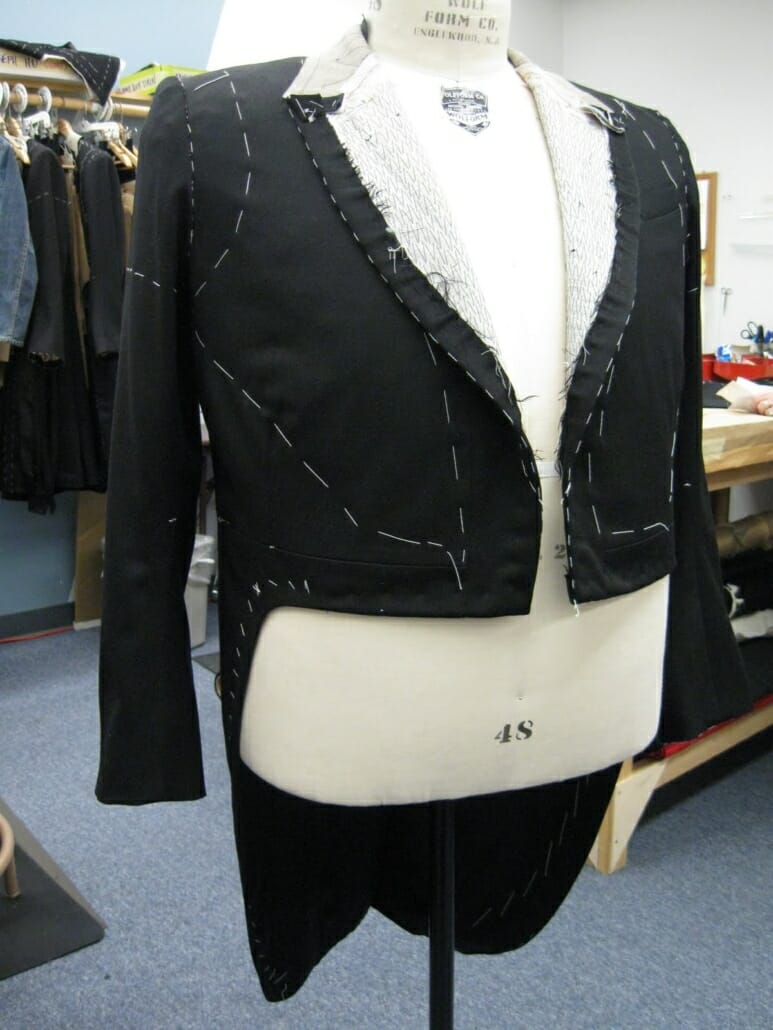

The evening tailcoat is further differentiated in that it must fit the torso snugly even though it is cut so that it cannot be closed or buttoned. This can only be accomplished by having it contour to the wearer’s body perfectly. Therefore, unless a man has proportions virtually identical to a pre-made tailcoat, he will need to invest in the considerable expense of dress suit that is custom made for his physique.

Whether pre-made or made-to-measure, a well-fitting tailcoat offers significant benefits to the wearer. “This garment can turn any many into an Adonis,” says author Nicholas Antongiavanni, “be he short or gangly, fat or lanky” because its cut “accentuates every potential virtue while ruthlessly suppressing every conceivable vice.”

Body

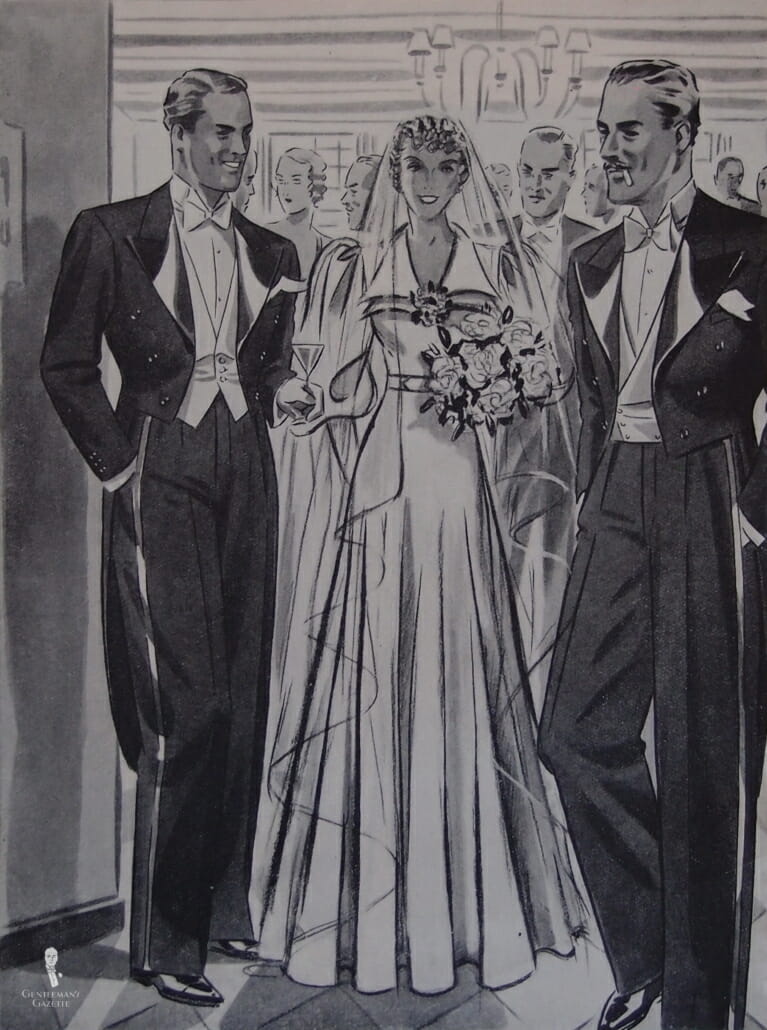

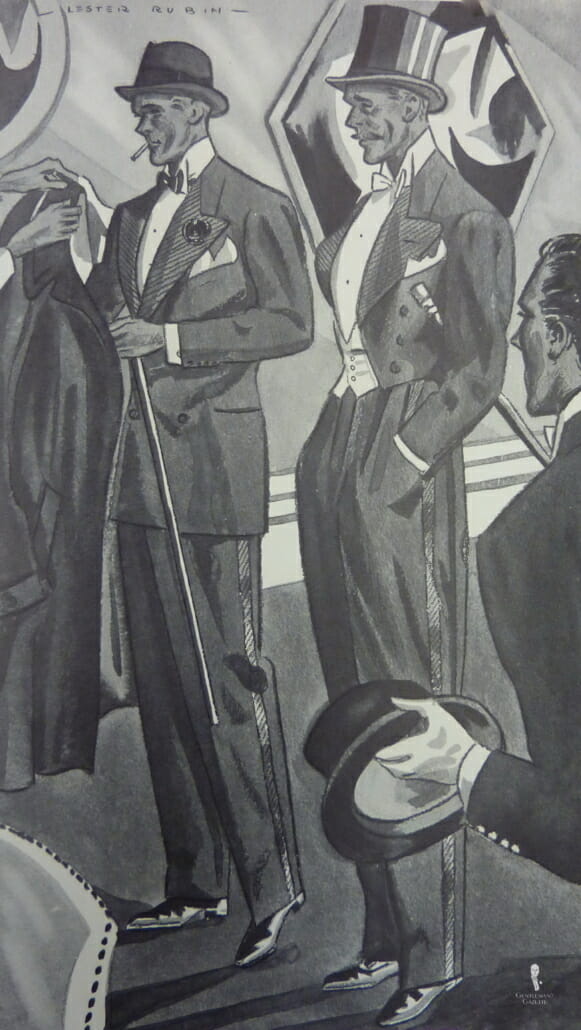

The full-dress tailcoat’s design is particularly efficient at adding stature to shorter men due to its ability to visually elevate the waistline. Like any tailored jacket, the tailcoat’s waistline typically mirrors the wearer’s natural waistline but unlike other jackets the coat fronts – and corresponding white waistcoat – end shortly below the waistline. And because the dividing line between the white waistcoat and the black trousers visually breaks the body into vertical halves, the deliberate raising of this line gives the impression of longer legs. Diminutive hoofer Fred Astaire employed an exaggerated waist height to great effect in his flawlessly tailored full-dress suits and it was also favored by the English in the 1930s for its dramatic aesthetics.

Like the waistline, other construction details of the coat’s front can vary according to changing fashions but the practices described in a 1913 issue of Vanity Fair have been the norm ever since:

The front effect of the coat is best when well opened, exposing considerable shirt, the lapels rolling to a little below the top button of the waistcoat from where the line slants away to the edge which inclines slightly upward and rounds into the skirt.

As for the rear of the coat, Manual of Politeness dictated in 1837 that “Not a crease should be discernible in the back or tails” and this still holds true. In addition, the collar of the coat must fit snugly at the neck and rise just high enough to cover the shirt collar’s rear stud and the bow tie’s band while still allowing a significant portion of white to remain visible.

Sleeves

Fred Astaire’s famous tailcoats also incorporated the requisite high armholes that prevented the coat’s sleeves from pulling at the body no matter the position of his arms, a feature that is just as relevant to today’s formal dancers. Similar to the collar, sleeves should be cut short enough to reveal “a gleaming expanse of white linen at the cuff”, ranging from half an inch to one inch depending on the wearer’s height. Tailcoat sleeves are also relatively narrow, traditionally just wide enough to allow the shirt cuff to slip through.

Skirt (Tails)

A center vent that rises up to the waistline divides the coat’s skirt into two “tails” which originally inspired the nicknames swallow-tail coat and claw-hammer tailcoat. The tails generally extend down to the bend of the knee in a straight line with a gentle curve at the bottom.

Lapels

The peaked lapel has been standard since the turn of the twentieth century. Not only is it the most formal style of suit lapel but its sweeping upward diagonal lines also create the impression of a powerful V-shaped torso.

Connoisseurs of vintage formal attire may occasionally stumble across a shawl-collared tailcoat from the interwar years and wish to adopt the style. If so, they should view it in context of an era when full dress was worn so frequently that gentlemen naturally sought an alternative take on the classic.

Unless one’s social calendar is chock full of white-tie events, it is best to leave the shawl collar to the sartorial history books.

Some modern designers like to dress the ultra-formal tailcoat with the business suit’s informal notch lapel. The only reason for choosing this paradox would be to ensure your fellow guests know that your clothing is rented.

Other Considerations

Most other aspects of a coat’s cut are purely aesthetic and therefore subject to changing fashions. This includes the amount of drape (fullness over chest and back), amount of shoulder padding and size and curve of the lapels. See Style Basics for guidelines that will help make a suit as timeless as possible.

Tailcoat Fabrics: Black or Midnight Blue in Wool, Mohair, or Blends

Black has been the norm for evening wear since the 1850s and midnight blue has been a correct and striking alternative since the 1920s. The most common fabric since the late Victorian era has been worsted wool with an understated finish such as barathea which is preferred by Britons. Mohair and wool blends have been an acceptable alternative since the late 1950s, favored for their ability to add a tastefully dull sheen to the suit.

The characteristics of midnight blue and worsted wool are discussed in detail in the description of Classic Dinner Suits.

Perfecting the Tailcoat Finishes: Lapels, Buttons, and Pockets

Lapel Finishes

The best lapel facings are made of pure silk while less expensive ones contain a synthetic component. The silk can take the form of smooth satin or the dulled ribbed texture of grosgrain. Although the former is much more common in North America its shiny, somewhat theatrical finish is not as popular in Britain where the understated look of grosgrain is often preferred.

The left lapel should have a working buttonhole for a boutonniere (known in Britain, ironically, as a buttonhole). Quality formal coats will also include a stem holder on the reverse side of the lapel. This is typically a very small cord that keeps the stem in place so that the flower does not fall out of one’s lapel over the course of an evening of dancing and dining.

Buttons

Because the double-breasted evening tailcoat has not been designed to close since the 1820s, the two rows of front buttons have become purely decorative.

There are three buttons in each diagonal row and their spacing is a matter of style. Sleeves buttons are also ornamental: there should be four of them spaced closely together beginning about half an inch from the end of the sleeve. In the 20s and 30s one could also find tailcoats with just 1, 2 or 3 sleeve cuff buttons.

Unique to the tailcoat and morning coat are the two buttons found at the back of the waistline, a vestige of a time when the coat’s tails were folded up and buttoned to the back for convenience when riding on horseback.

All buttons can be covered in the same facing as the coat’s lapels or in cloth but simple black buttons or textured ones are acceptable as well.

Pockets

“In company, as little as possible should be borne in pockets of the coat ; indeed, a full-dress coat should be made without pockets”. The reasoning behind this salient advice from an 1837 etiquette manual is that the weight and bulge of loaded-down pockets will obstruct the graceful lines of the contoured dress suit. Thus, hip pockets are never seen on a tailcoat and a breast pocket (introduced in the Edwardian era) is left empty by more fastidious dressers.

This lack of pockets presented a dilemma for nineteenth-century gentlemen who were expected to remove their otherwise mandatory dress gloves when dining. In typical English fashion, Regency dandy Beau Brummell had his tailor hide pockets in the inside folds of the coat’s tails and this remains a feature of better tailcoats to this day.

Full-Dress Trousers: Elegance from the Ground Up

Full-dress trousers are constructed of the same fabric as the tailcoat. Because it is essential that they sit just above the bottom of the coat’s fronts they must be cut with a high rise (waistline). And because it is equally essential that they remain there throughout an evening of spirited ballroom dancing they must be cut for, and held up with, suspenders (braces in the UK). They can be constructed with flat fronts as they were prior to the 1920s or with pleats as has been popular since the advent of baggier fashions following the First World War.

A primary characteristic of formal clothing is the concealment of its workings and fastenings. This can be seen in the aforementioned silk-covered coat buttons, the decorative studs in a formal shirt and the trim that covers the outer seams of formal trousers.

This silk trim, also known as galon, is either satin or grosgrain to match the coat’s lapels and consists of either one wide stripe or two narrow stripes to differentiate it from tuxedo trousers. (Apparently this is derived from the military practice of using double stripes to indicate higher rank.)

In the past, braid was also used for this purpose but today the term is often used generically when referring to trouser trim in general. The evening suit’s refined minimalism is further aided by the placement of the side pockets on the trouser’s side seam rendering them virtually invisible.

Finally, formal trouser legs are always plain as cuffs (turn-ups in UK) are too casual (they originated as a mudguard) and would interfere with the side braid.

Dress Decorum: Sitting Secrets

When sitting in a tailed coat do not divide the tails but carefully place them over the side or back of the chair.

Formal Facts

Well Suited: High Arm Scyes

A coat’s arm scye is the hole where the sleeve meets the body. High arm scyes allow the sleeves to move independently so that the body will stay in place when the wearer moves his arms. Consequently, this is a standard feature of tailcoats that are custom made for orchestra conductors.

(Not So) Well Suited: Avoid Tailcoat Travesties

Many mainstream manufacturers offer the business suit’s notched lapels on their tailcoats, often with fancy trim. They also like to market their white-tie tailcoats with black-tie accessories. Steer well clear of such prom wear.

Cut & Fit in Depth

Whether renting or buying, be sure to consult the Style & Fit section for much more information on the proper fit of a suit.

“Tuxedo Tails?”

A tailcoat is no more a tuxedo than a pocket watch is a wristwatch. However, as the dinner jacket’s popularity eclipsed that of the evening and morning tailcoats in the US, Americans came to think of “tuxedo” as synonymous with “formal wear”. Rather than trying to explain the difference, retailers and fashion magazine writers simply adopted the fallacy.

Well Suited:

Double-Duty Trousers

If you opt for a custom tailcoat consider ordering a dinner jacket too and sharing a pair of tuxedo trousers between them. Single-striped trousers are an acceptable alternative with full-dress and in fact were the only formal trousers that the estimable Brooks Brothers used to sell with their tuxedo and tailcoat separates. On the other hand, if you put in the effort of having tails made you might as well go all in, and get the double galon white tie trousers as well.

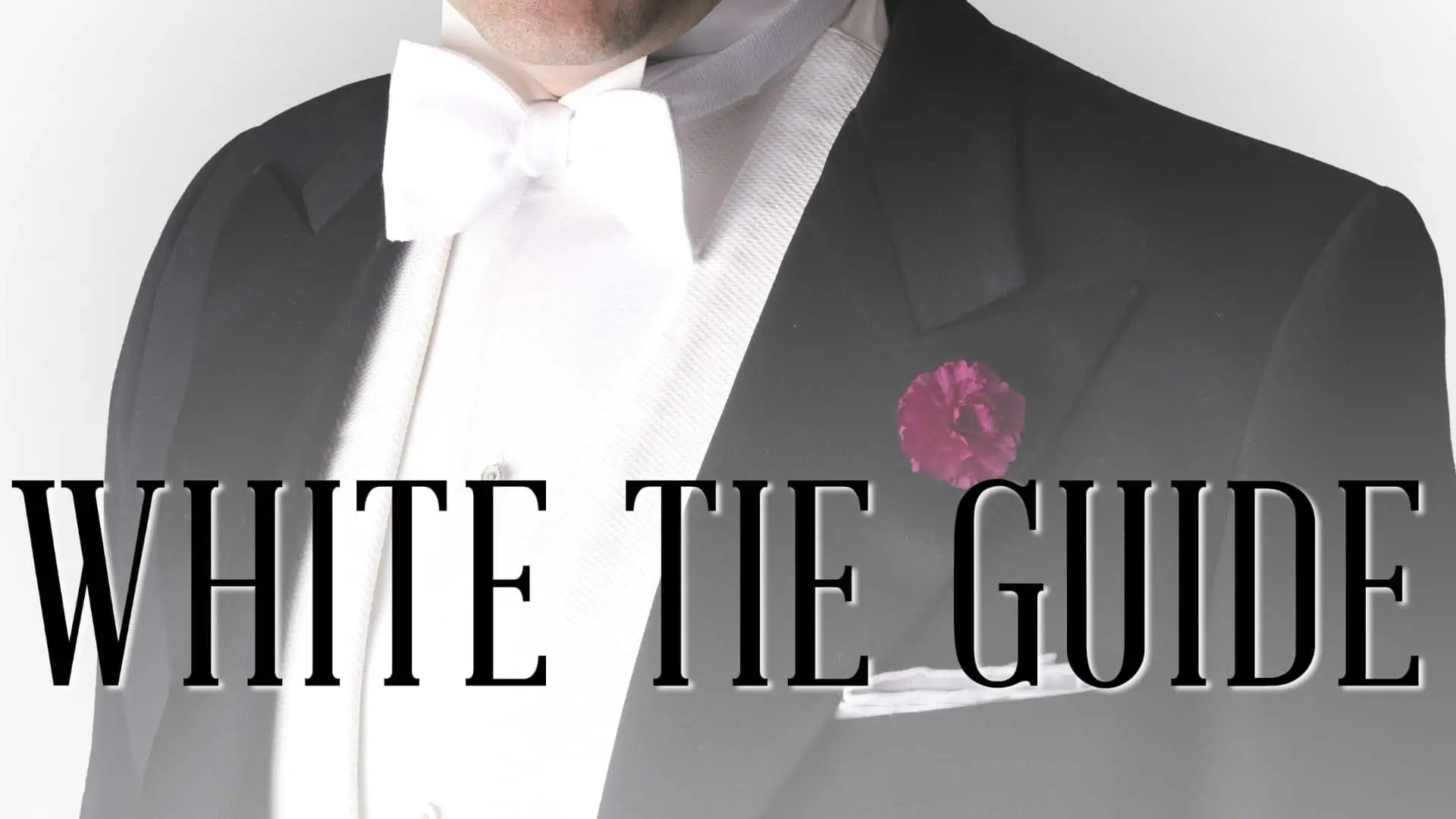

Explore this chapter: 10 White Tie Guide