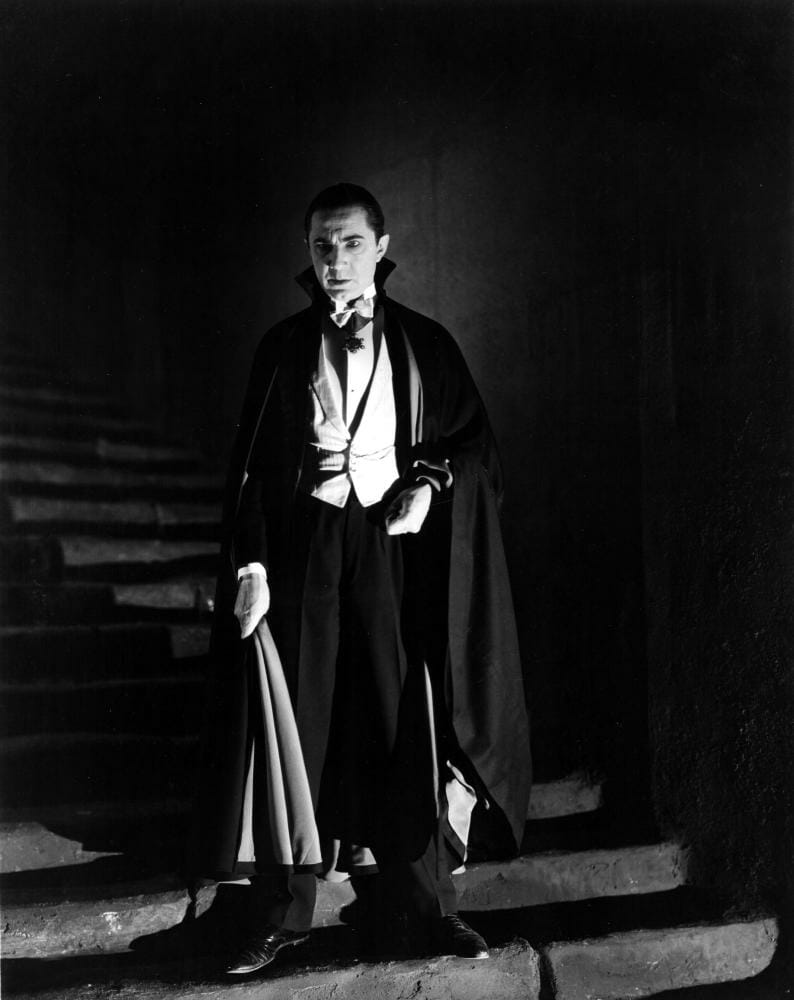

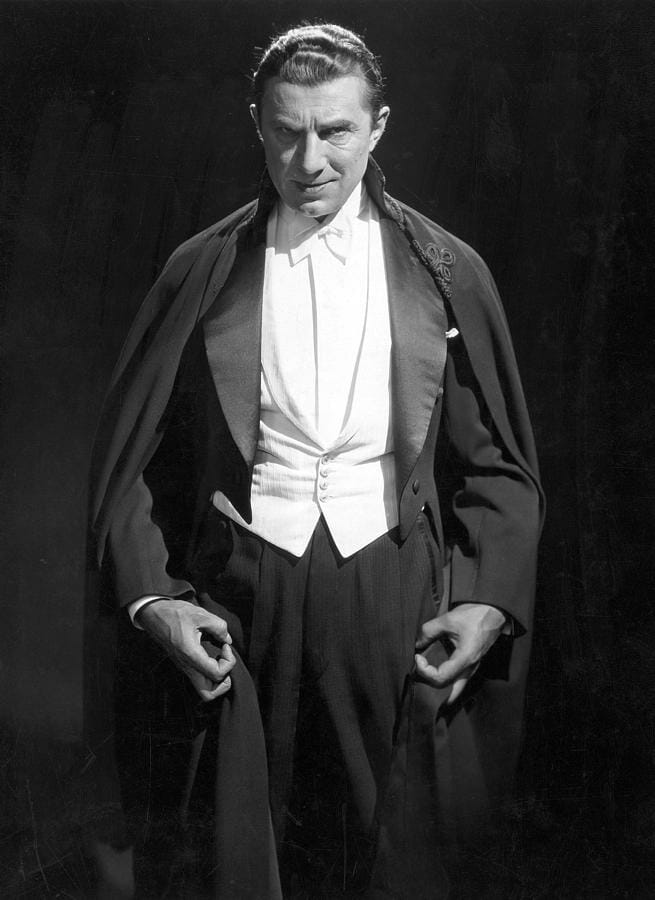

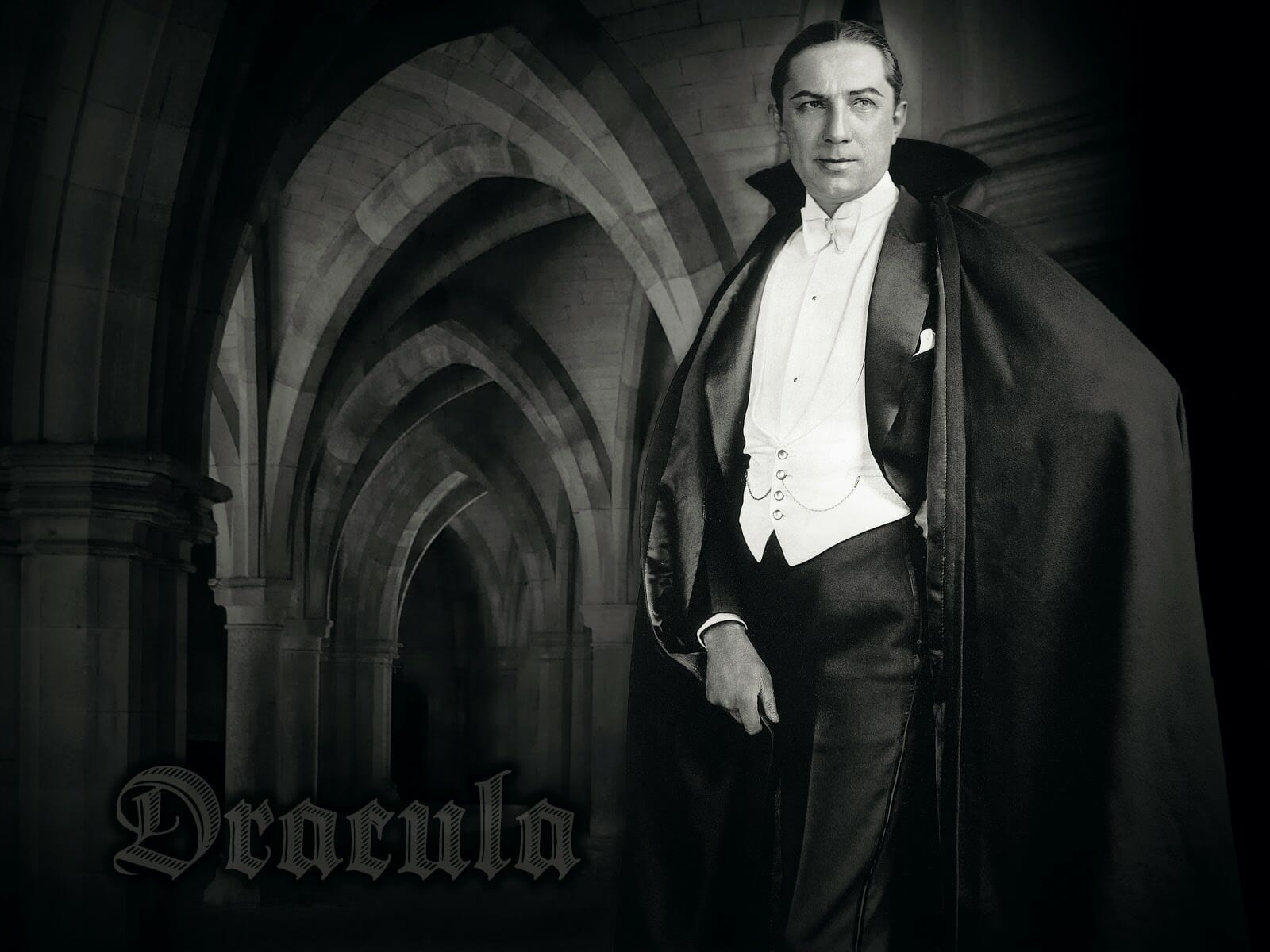

Next to Fred Astaire, Bela Lugosi’s Count Dracula is arguably history’s most recognizable embodiment of White Tie.

The legendary vampire’s association with formal evening wear arose not from the original 1897 novel but from a 1920s London stage adaptation by Hamilton Deane. The evolution is described in Bram Stoker’s Dracula: A Reader’s Guide:

Another major innovation was the styling of the Count as a gentleman in outline rather than as an instantly recognizable degenerate. Deane’s vampire wore contemporary evening dress – the white tie, tailcoat and opera cloak that remains a signifier of vampirism to the present – rather than the frogged frockcoat of Graf Orlock [the vampire in the 1922 unauthorized German adaptation Nosferatu], or the unexceptional dress affected by Stoker’s Count . . . The vampire is now not merely a figure so unexceptional that it could move without comment across London, but it is also aligned with the establishment, with domestic signifiers of power and wealth rather than with visible foreignness.

Beginning in 1924, Deane’s adaptation toured Britain successfully before arriving at London’s West End in early 1927. It was here that an American impresario obtained the rights to revise the play and bring it to Broadway later that year with Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi in the title role. This casting signaled a further significant change to the already modified Count of Deane’s production as described in Hollywood Gothic. The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen:

The London Dracula was middle-aged and malignant; Lugosi presented quite a different picture: sexy, continental, with slicked-back patent-leather hair and a weird green cast to his makeup – a Latin lover from beyond the grave. Valentino gone slightly rancid. It was a combination that worked, and audiences – especially female audiences – relished, even wallowed in, the romantic paradoxes.

Though not the Universal Studio’s first choice, Lugosi was signed to play the vampire in the first authorized film version of Dracula, released in February 1931. And the rest is vampire history.

Happy Hallowe’en!

I love his cloak. On the other hand, Lugosi’s opera cape wearing vampire is doubtless one of the reasons that no man could ever hope to wear an evening cloak again and be taken seriously.

I see he puts the wings of his wing collar in front of the bow tie – in order to give the impression of white fangs at the neck, I suspect.

I wonder if the decision to clothe Dracula in white tie for the London stage production owed something to the very popular villainous foe of Sexton Blake, Zenith. Although both names have faded from the general consciousness, Sexton Blake was the most famous of all the detective adventurer type characters that existed in the popular fiction of the day and Zenith was an adversary who had been around for ten years at that point and was to continue in print through the second world war. Zenith – an albino crime lord with a penchant for opium cigarettes and possible middle European princeling – always wore white tie and tails, no matter the occasion. The association of pallid glamorous villain with white tie was one that was already in the air before Dracula made it his own.

Hal: I don’t know if that was intentional. Back then you saw men wearing them in front of the tie a lot. There was no fixed rule.

Thanks for writing about this, Peter.

Happy Hallowe’en!