Tuxedos and tailcoats aren’t just for men. In this section, you’ll learn about the history of women wearing tuxedos and tailcoats and the conventions, as they exist today, for women dressing in this mode.

Pre-War: Androgynous Glamor from Gladys Bentley to Marlene Dietrich

According to fashion historian Amber Jane Butchart, in the mid-nineteenth century, American female reformers caused so much controversy by dressing in masculine attire that they abandoned the practice for fear of overshadowing the social reforms they were advocating. Yet many male impersonators rose to fame during this time by adopting the very same garments.

Probably the most famous of them was Vesta Tilley, the highest paid woman in Britain in the late Victorian era. Although she played many characters her most popular ones were rakish men-about-town which required her to regularly don male formal attire. These types of acts, says Butchart, set the stage for future female performers to similarly defy social convention.

Performers, however, being the operative word here. It was considered acceptable for female stars to dress in male attire long before it was anywhere near admissible for the general population, the assumption being that the performative state of the wearer either on or off stage was essentially a Get Out of Jail Free card for flamboyance.

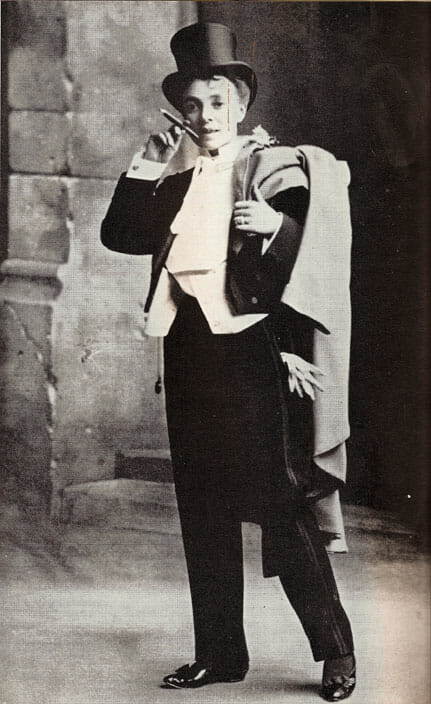

Gladys Bentley

As the popularity of vaudeville declined following World War I, cross-dressing performances transitioned to nightclubs and burlesque revues. Accordingly, the next woman to achieve celebrity status in men’s formal wear was Gladys Bentley, an African-American blues singer popular during the Harlem Renaissance. She appeared in the 1920s at Harry Hansberry’s “Clam House”, one of New York City’s most notorious gay speakeasies, and headlined in the early thirties at another Harlem club backed up by a chorus line of drag queens, appealing to audiences of all races and sexual orientations. Whereas Tilley went out of her way to maintain respectability onstage and femininity offstage, Bentley was quite the opposite.

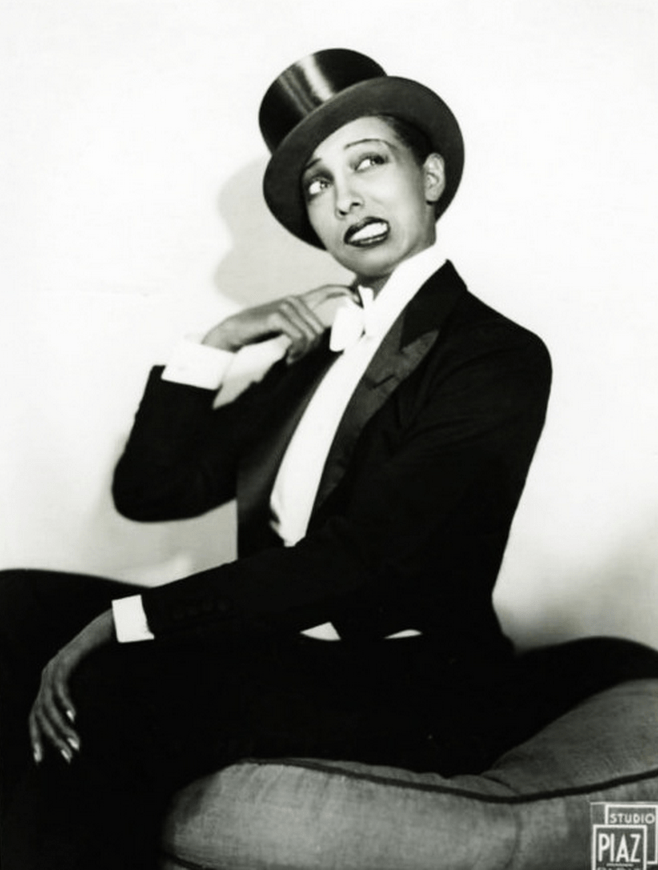

Josephine Baker

Singer, actor, and dancer Josephine Baker was another Harlem Renaissance performer who was open about her alternative (bi)sexuality. She gained her greatest fame though when she moved to France in 1925 and opened in an all-black revue in Paris where she was an instant success for her erotic dancing and near nudity on stage. Then in 1932 she starred in another revue called La Joie de Paris where she played against type and appeared as a bandleader in white tie and tails. She would go on to be the first African-American female to star in a major motion picture – Zouzou (1934), alongside Jean Gabin – and to become a world-famous entertainer.

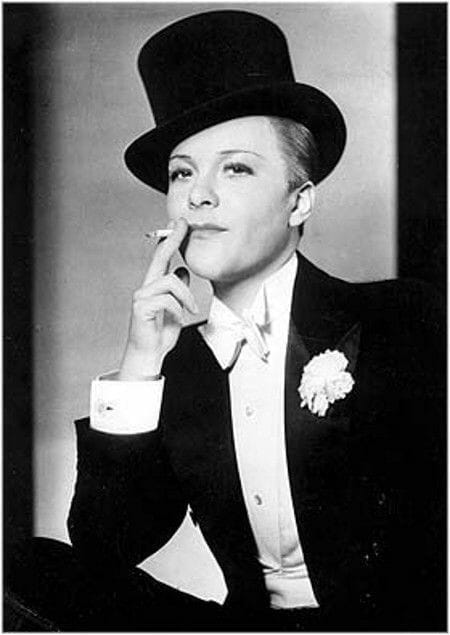

Marlene Dietrich – The Most Famous Woman in Tuxedos, White Tie & Men’s Clothing

Around the same time that Baker was making a splash in Paris, a German stage and screen actress was emerging as the most famous formal cross-dresser in history. Marlene Dietrich already had a penchant for wearing men’s clothes in general and men’s formal wear in particular when she starred in her breakthrough German film Blue Angel in 1930.

Her performance caught the eye of Paramount Pictures who wasted no time in signing her and releasing her first American film, Morocco, later that same year. The film includes a now legendary scene in which Dietrich, playing a cabaret performer, saunters onto the stage in a Moroccan nightclub dressed in full white tie. Accustomed to seeing much more revealing costumes the cabaret audience boos the lady with the audacity to cover her legs.

However Dietrich’s character wins over the fictional audience with her gutsy act – including kissing a woman in the crowd – just as the actress herself won over film audiences and propelled herself to international stardom. The discreetly bisexual star who once confided “I think I am much more alluring in these clothes” continued to turn heads occasionally by donning men’s formal attire both on screen and off.

Renate Müller

Renate Müller was one of the most famous German actresses in the 1930s. She appeared in dozens of films and revues, often assuming male garb. As the National Socialist party rose to prominence in Germany, party officials attempted to utilize Müller as part of their propaganda machine, holding up her as a superior replacement for Dietrich, who had emigrated to the United States.

Müller refused, however, and her career in Nazi Germany was effectively over. In 1937 she died under mysterious circumstances, and it has been variously asserted that she died of an epileptic fit, was murdered by Nazi agents, or killed herself.

And so it was that the initial chapters of the formal cross-dressing story all featured a common theme: the women were performers and their attire almost universally a literal interpretation of the male white tie dress code.

Despite countless inaccurate references to their attire as tuxedos, female appropriation of black tie was in fact extremely rare possibly because it too closely resembled a regular men’s suit and therefore implied a normative fashion choice. This restrained approach would be turned on its head during the social upheaval of the 1960s thanks to an haute couture designer by the name of Yves Saint Laurent.

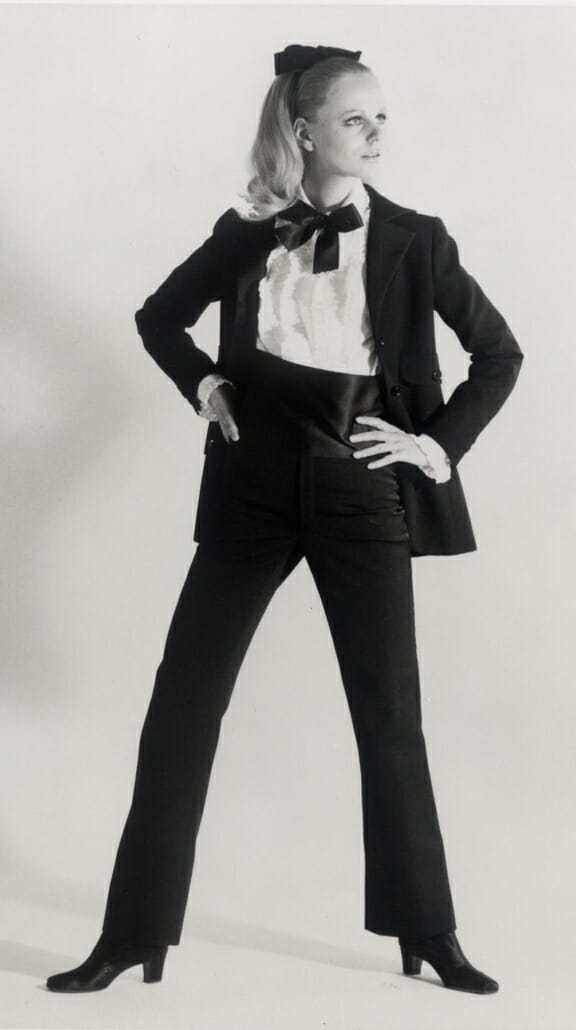

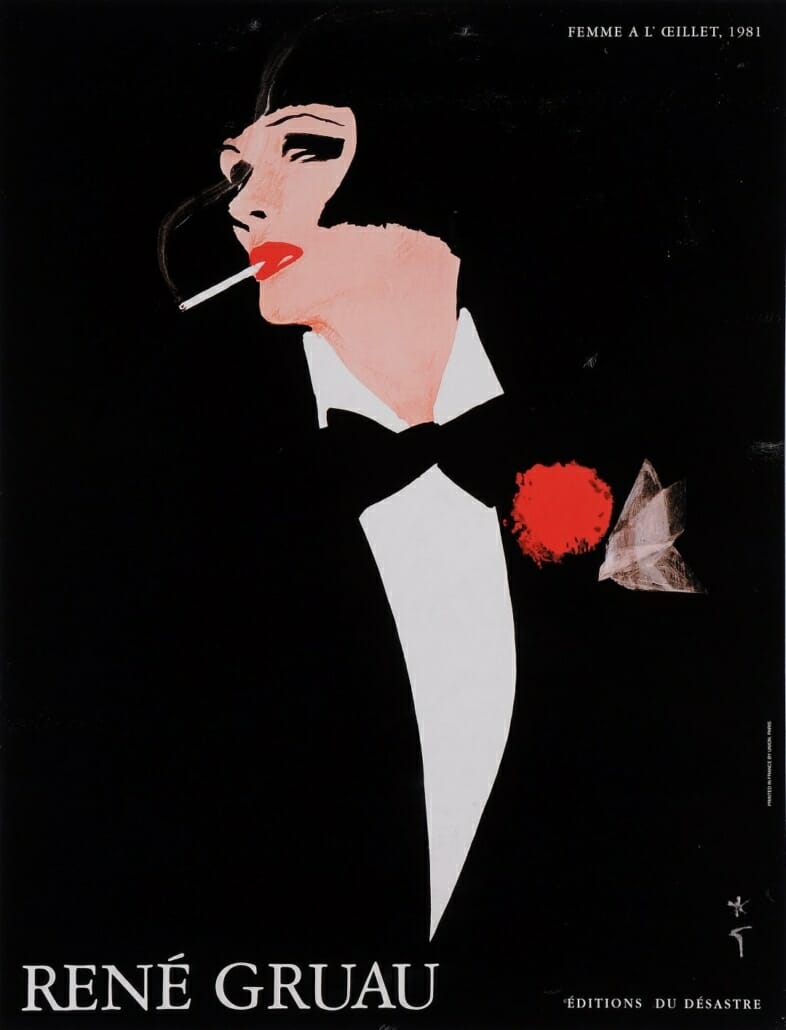

Counterculture Ladies in Menswear: Le Smoking

Saint Laurent’s le smoking debuted on the runways of Paris in the fall of 1966. This suit for women – named for the French term for “tuxedo” – pioneered minimalist, androgynous styling for ladies. Rather than hiding the female form under boxy male attire, the famous couturier had re-designed the attire to complement a woman’s natural curves. Constructed of velvet or wool the suit was originally presented with a cummerbund or a matching waistcoat, high-heeled black satin boots and white frilly blouse and was finished at the neck with an oversized silk bow.

Saint Laurent’s innovation was met with shock and consternation at a time when women in trousers was still very much frowned upon and in some places was even illegal. However, it was also a time of female liberation which made for a perfect match. In handing women their own version of a suit previously reserved for society’s dominant males, Saint Laurent inspired his partner to state that “Chanel gave women freedom, but YSL gave them power.” French actress Catherine Deneuve provided a more intimate perspective: “The thing about a tuxedo is that it is virile and feminine at the same time. It really does make you feel different as a woman, it changes the gestures.”

Soon after his paradigm-changing creation appeared on the couture runway, Saint Laurent launched his hip ready-to-wear Rive Gauche label with affordably priced “smoking suits”. The suits – quickly dubbed “pantsuits” – were a big hit with young women and have continued to influence fashion designers’ collections to the present day. Like any other fashion, interpretations of le smoking have varied with time. They have ranged from formal suits so skimpy they practically resembled lingerie to very masculine cuts offset by high heels and worn over a bare chest (Studio 54 regular Bianca Jagger was famous for this look). This kind of versatility attests to the suit’s role as attire that’s more dressy than formal.

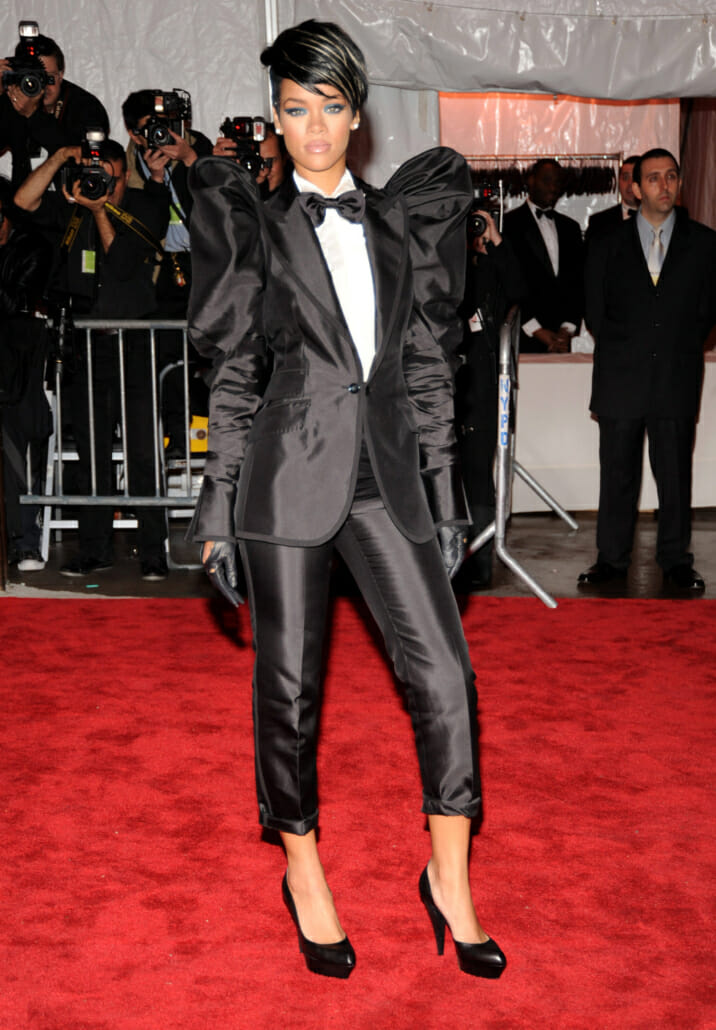

Women’s Tuxedos Today

The women’s tuxedo continues to be popular on the red carpet and in fashion spreads with Ellen Degeneres and Tilda Hinton being arguably its biggest proponents. Now the latest celebrity to champion the women’s tuxedo is young soul singer Janelle Monáe. She not only featured it in the video for her 2010 debut hit “Tightrope” but has made it into the basis of her signature wardrobe. Said Monáe in an interview with Honey magazine:

I bathe in it, I swim in it, and I could be buried in it. A tux is such a standard uniform, it’s so classy and it’s a lifestyle I enjoy. The tux keeps me balanced. I look at myself as a canvas. I don’t want to cloud myself with too many colors or I’ll go crazy.

Lesbian Weddings: Gender Inversion

The latest development in the story of women and tuxedos lies not at Hollywood galas or Paris couture houses but in backyards and banquet halls hosting 21st-century phenomena: same-sex weddings. A random sampling of online photos of lesbian ceremonies reveals that the apparel at such weddings is generally divided into three categories:

- Traditional wedding gowns for both partners

- Other types of conventional women’s clothing for both partners

- Gowns or conventional women’s clothing for one partner and tuxedos or other conventional male attire for the other

Among this third subset, the male attire is part of a much broader gender identity (often labeled as “butch” versus “femme”) whereby the corresponding partner adopts other masculine traits, most notably closely-cropped hair and lack of make-up. By consciously dressing themselves as grooms these partners reject the appropriation of symbolic male apparel and celebration of the female mystique that is embodied in Saint Laurent’s le smoking and its imitators. Instead, their choices harken back to the pre-war custom of employing men’s formalwear to conceal a woman’s body and, by association, her femininity. In many ways, they are modern-day Gladys Bentleys.

The butch/femme lesbian wedding phenomenon has actually become popular enough to give rise to at least one online retailer specializing solely in women’s tuxedos and accessories. However, based on the improper fit of the formal suits in the photos of such weddings, the majority of masculine lesbians appear to prefer standard rental tuxedos designed for men. This may be due to a typically male indifference towards (or ignorance of) how tailored clothing is supposed to fit. Or it may simply be a matter of fiscal prudence as few men can justify the purchase price of a formal kit in today’s informal world, let alone women.

With the rising popularity of tuxedos at lesbian weddings, it is quite possible that lesbian proms may not be far behind. Take, for example, the case of a lesbian high school student in Mississippi who sued her school in 2009 for the right to wear a tuxedo rather than a gown for her graduation photos. (She won . . . sort of. The school district decided to instead ban either type of traditional formal dress in favor of gender-neutral graduation gowns.) As school-sanctioned discrimination towards gay students is increasingly legislated into history, a whole new market may be opening up for tuxedo rentals.

Formal Facts

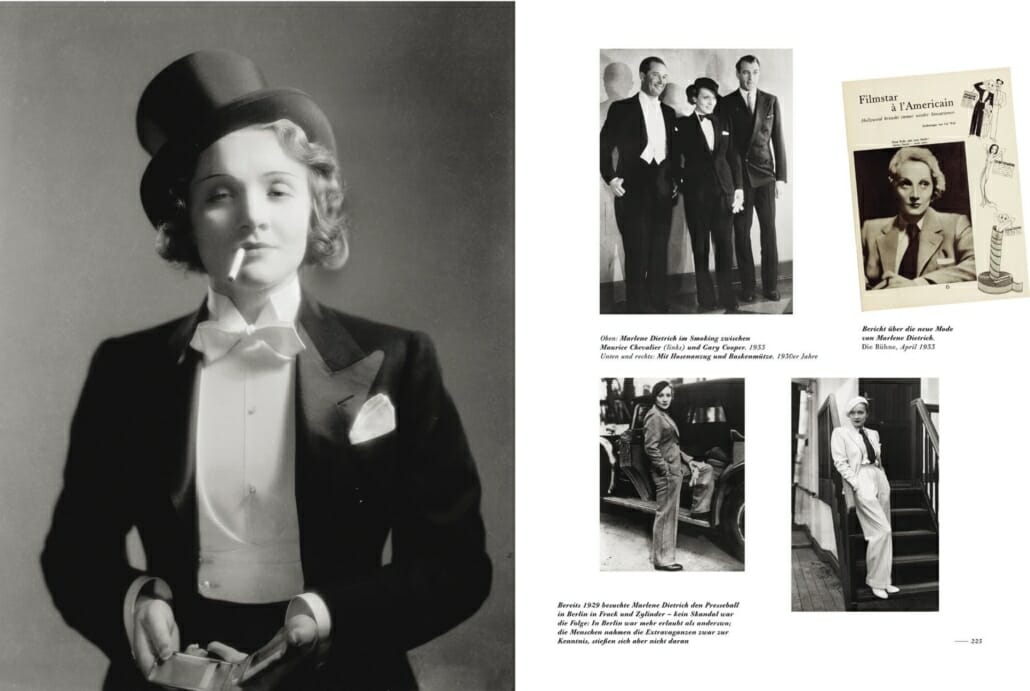

Style Icons: Marlene Dietrich

Although most associated with Morocco, Marlene Dietrich’s formal cross-dressing is also captured in some lesser-known images. The still above is from her 1932 film Blonde Venus while the picture below was taken at the premiere of The Sign of the Cross that same year. Dietrich stole the spotlight when she appeared on the red carpet dressed in black tie.

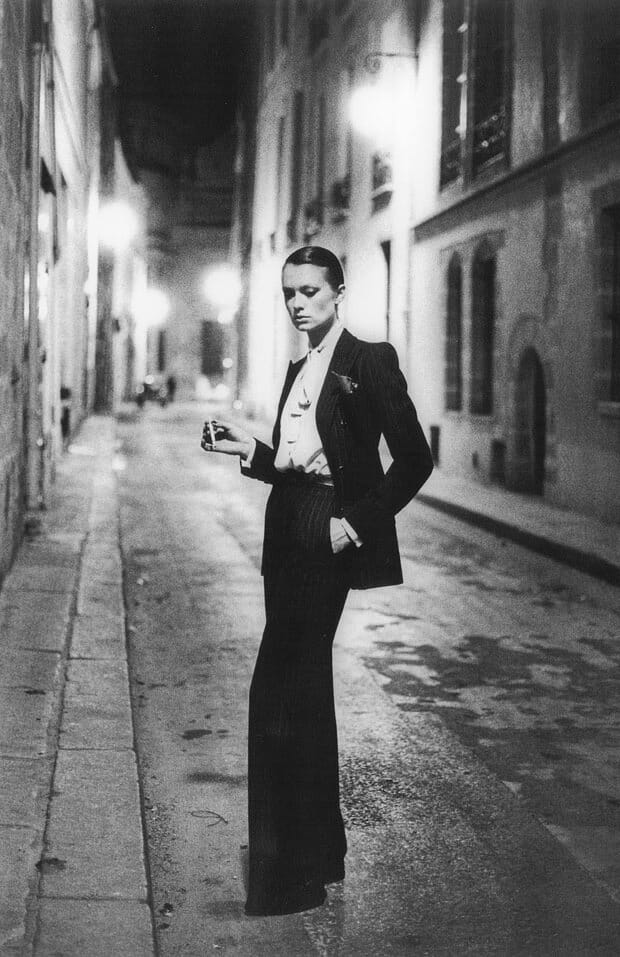

Le smoking

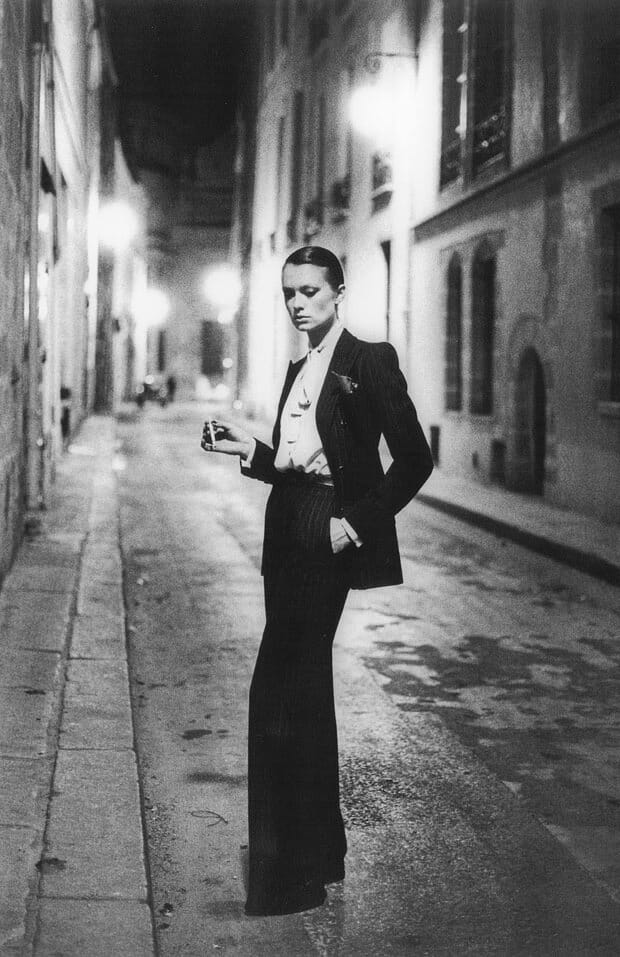

This 1975 image is the one most associated with the Yves Saint Laurent’s groundbreaking women’s tuxedo but it actually depicts a pinstriped suit designed in the same vein. For the complete story of le smoking see Vogue magazine’s “Voguepedia.”

Explore this chapter: 9 Advanced Black Tie & Tux Coverage

- 9.1 Black Tie, Tuxedo & White Tie Evening Wear Glossary

- 9.2 Black Tie Dress Code for Women – Ladies’ Evening Wear

- 9.3 Tuxedo Black Tie Myths & Merits Debunked

- 9.4 Orders Decorations & Medals with Black Tie & White Tie

- 9.5 Clerical Formal Wear

- 9.6 Military Formal Attire – Mess Dress

- 9.7 Scottish Highland Dress, Irish, and Welsh Formal Black Tie & White Tie Attire

- 9.8 Women’s Tuxedos and Tailcoats

- 9.9 Smoking Jacket Guide

- 9.10 Formal Evening Wedding Attire & Etiquette

- 9.11 How To Wear A Tuxedo Like James Bond