Silk is one of the most important fabrics in menswear history, and it remains a sign of luxury and taste even today. So, we’ll deep dive into the popular luxury fabric and understand why it’s so well-loved but also steeply priced.

Even the word “silk” itself has become something of a shorthand for decadence and elegance. Think of hygiene products that promise “silky” smooth hair or skin, for example, or the Galaxy chocolate advertisement that asks, “Why have cotton when you can have silk?”

It’s quite clear, then, that silk has a reputation for richness. That being said, we’d like to understand why is so associated with luxury and why it is so expensive.

Before we get to it, though, just a note that today’s guide is another installment in our ongoing series on just why certain materials cost so much. We’ve previously discussed cordovan leather as well as leather made from crocodile and alligator skins.

The History of Silk

Let’s start off by spinning a tale that starts in Ancient China. The oldest evidence of silk production dates back to the Yangshao culture of Neolithic China. Silk had likely been produced in the region since 4,000 BC and, possibly, even longer.

According to popular stories, the pseudo-mythological Chinese empress, Lei Zhu, invented sericulture, a fancy word for the cultivation of silkworms for silk production. That’s right. In case you didn’t know, silk comes from insects. They use it when building their cocoons in a process called “metamorphosis.” Caterpillars metamorphosing into butterflies is a common example.

Meanwhile, as the story goes, while drinking her hot tea in the shade of a grove one day, a cocoon fell into Lei Zhu’s teacup. The heat of the tea caused the cocoon to slowly unravel and Lei Zhu realized that the long fiber could be used to make thread. Lei Zhu began to collect other cocoons, and she made silken thread from them.

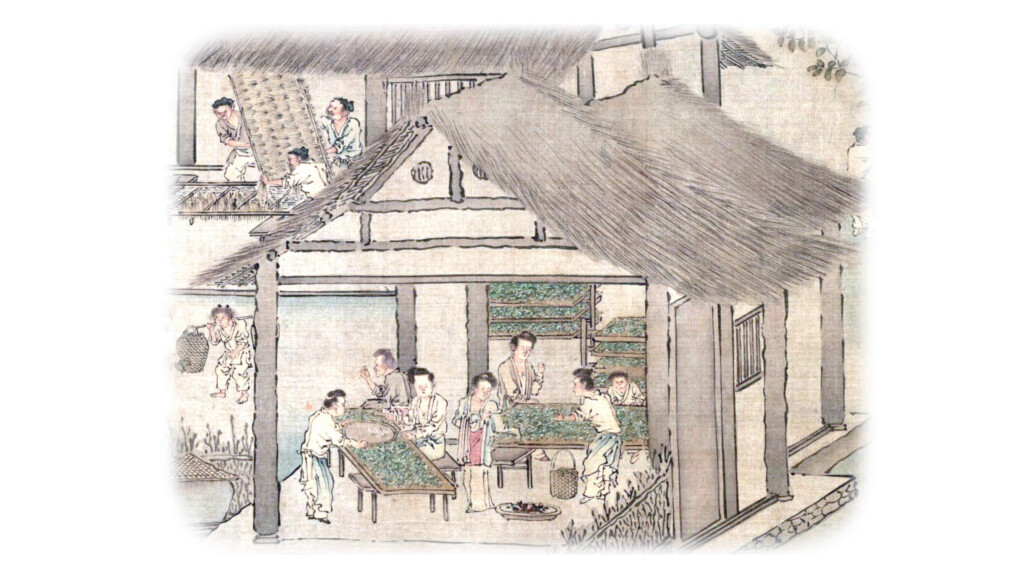

Through the centuries then, silk production in China was standardized, and you can see the entire historical process on this beautiful picture scroll from the 12th century AD. Here, silkworms are gorged on mulberry leaves to encourage them to begin spinning their cocoons. In this detail, we see reed frames being prepared where the cocoons will be hung. Here, the cocoons are weighed and sorted, then the fibers are soaked in boiling water to unravel them and kill the larvae so that they can be strung onto spools. Eventually, then, these spooled fibers can be made into silk fabric.

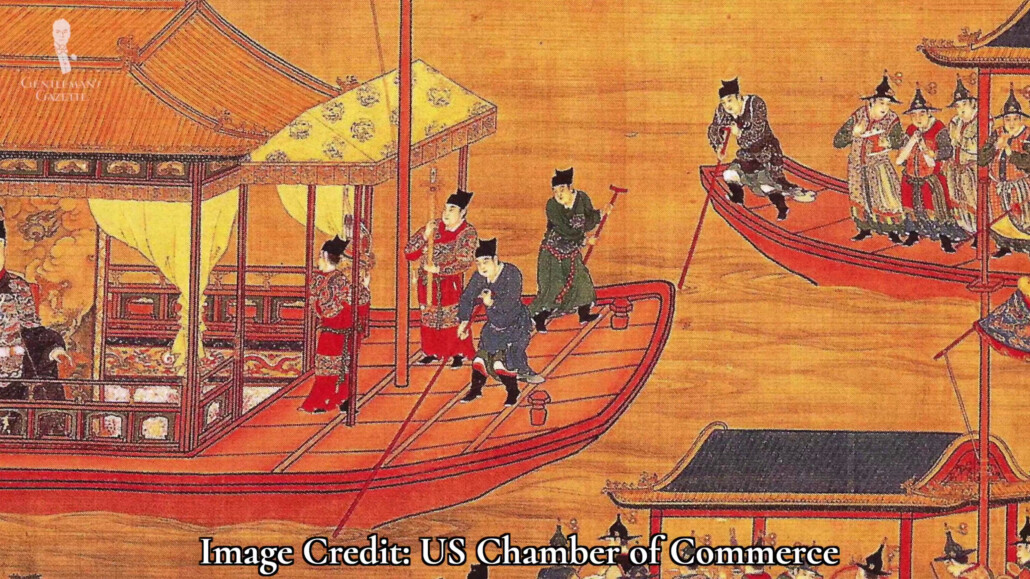

For centuries, China held a virtual monopoly on silk production, and they spread their silk across the world via an important network of trade routes – appropriately known as the “Silk Road” – beginning in the 2nd century BC. This trade network would eventually grow to encompass over 4,000 miles of roads and link together East and Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia, the Middle East, East Africa, and Europe.

Despite Chinese efforts to maintain total control over silk production, by the 2nd century AD, sericulture had spread to South Asia and, in the 6th century AD, merchants in the Byzantine Empire smuggled silkworms westward, beginning the production of silk in Greece.

Then, during the 12th century, Ruggero II of Sicily invaded Greece and brought silk production back to Italy with him. From Italy, production soon spread across Southern Europe, and silk quickly became one of the most important luxury fabrics in all of Europe.

In William Shakespeare’s play, Timon of Athens, silk is associated with luxury as decadent people wear silk, drink wine, and lie soft. And throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, silk was a common fabric for men’s suits and waistcoats. It would remain associated with luxury in the 19th and 20th centuries and up to the present day.

So, then, silk’s long and storied association with wealth and luxury still affects its cost today. This is because it has a legacy and a reputation of worth and is associated with decadence and exoticism, meaning that this social cachet also drives up the cost more.

Modern Silk Production

While the picture scroll we showed earlier gave an overview of the historical production methods for silk, modern production is quite a bit different. The modern silk industry generates about $3 billion in revenue per year and includes a multinational network of production and distribution. About 150,000 metric tons of silk are produced each year.

This is in contrast to something like cotton, where 25 million metric tons are produced annually. China is still the number one producer of modern silk, with over half of all silk coming from China, and as much as 90% of the world’s silk comes from Asia as a whole.

Silkworm Farming

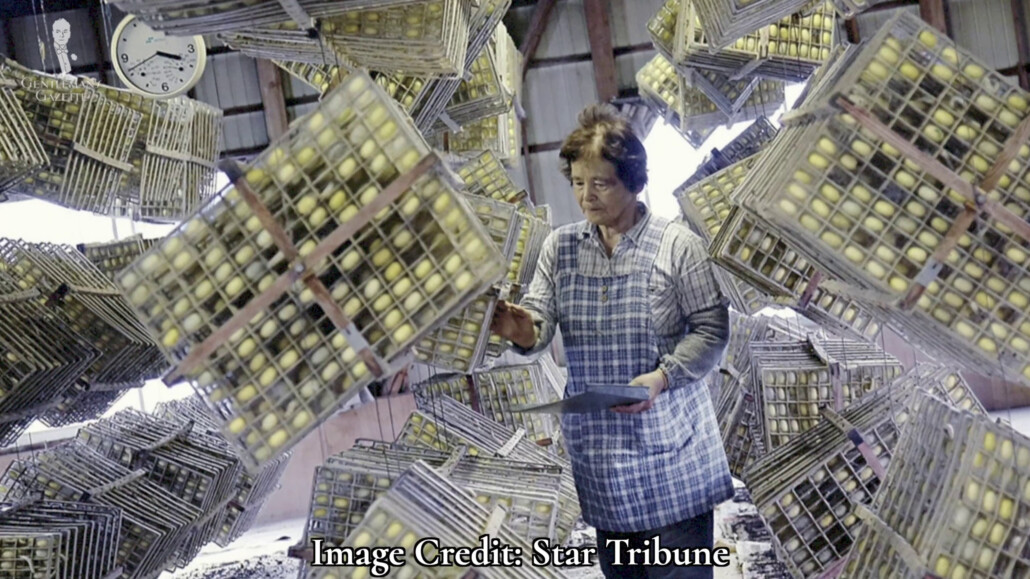

Several insect species produce silk fiber proteins, but the preferred insect for sericulture is the domestic silkworm, Bombyx mori. This is the worm, by the way, that metamorphoses into the silk moth. In some ways, modern silk production does look similar to historical production, but on a much more massive scale with considerable upfront costs.

For instance, a startup silkworm farm in Brazil needs equipment and supplies that can cost over $15,000. Compare this to the national gross income per capita in Brazil, which is just under $8,000. Meanwhile, on the other side of the spectrum, a massive Japanese silkworm factory opened in 2017 at a cost of $21 million.

Speaking of the value of supplies then, we’ll start with the silkworms themselves as modern silkworms have been selectively bred to produce the best silk. Larger silkworms produce larger cocoons and are therefore more valuable.

After hatching, silkworms will eat constantly and must be fed at least twice a day on a specific type of leaf. Silkworms eat mulberry leaves, and the white mulberry (or Morus alba) is believed to encourage the best silk production. Silkworms need to collectively consume about 140 kilograms of mulberry leaves just to produce one kilogram of raw silk.

Colonies of silkworms have to be closely monitored to prevent the spread of disease as silkworms are also prone to sickness. I guess that would make them sick worms. In any case, skilled laborers are required to make sure that the silkworms stay fed and healthy, which also brings up the overall cost of the finished silk.

Silkworm Harvesting

After one or two months, the silkworms start building their cocoons. At which point, they’re transferred to special racks. Cocoon weaving can take days, and during this time, the silkworm produces one continuous strand of silk that it wraps itself inside of, which, when unraveled, can stretch out to be three-quarters of a mile long.

As part of what’s known as a non-kill harvest, the silkworm pupae are allowed to emerge from their cocoons as silk moths after about one or two weeks. However, this process damages the cocoons when the moths break out and, therefore, under most methods of silk production, the pupae are killed before they’re allowed to emerge.

For some measurements, it takes about five thousand silkworms to produce one kilogram of raw silk or about 3,000 cocoons to produce one yard of fabric. After the cocoons are collected, they have to be unwound. This can be done by hand, but it’s usually done by machines in a process known as “reeling.” However, workers do still need to resolve clumps and extract any debris by hand.

These individual strands of fiber are extremely thin and fragile, and they need to be wound together with other fibers to increase the tensile strength. The resulting product is raw silk, which is then made into skeins.

Raw silk is essentially still a raw material, but it commands an impressive price. In 2021, raw Indian silk cost over $30 per kilogram, and, for contrast, Merino wool cost just $10 per kilogram. And in the grand scheme of things, the silk has only begun its journey.

Harvesting raw silk is a time and labor-intensive undertaking that has been automated to some degree, but still does require a fair amount of human oversight and handwork along the way. All of these factors, then, also contribute to the high overall price of silk.

Grading

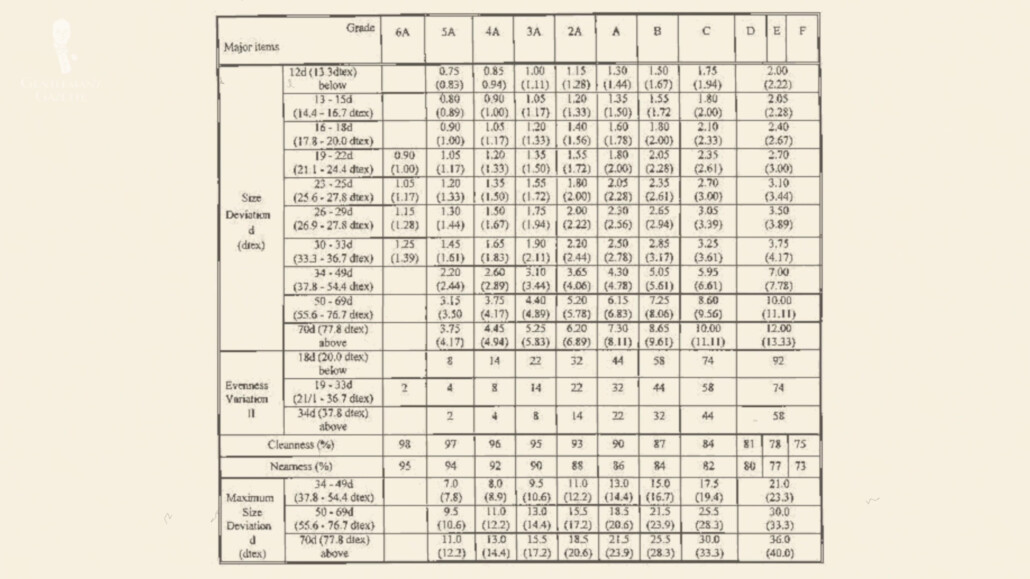

Before being made into yarn or fabric, the raw silk is then graded. Every country has its own standards, but because China produces the most silk, its standards are the ones most commonly used. China has 11 total grades, overall – 6A, 5A, 4A, 3A, 2A, A, B, C, D, E, and F.

This grading takes into account a variety of factors, including size deviation, cleanness, neatness, tenacity, elongation, and any defects. 6A is the highest possible grade, and less than one percent of Chinese raw silk is graded at this level.

To recap, then, not only do silkworms produce a relatively small amount of raw silk, to begin with. But, of this, only an even smaller amount will be allowed to be graded at the highest 6A quality.

In other words, not only is the overall supply of raw silk relatively low, to begin with, but the supply of high-quality raw silk is even lower. And, of course, what happens to prices when supply is low, and demand is high? They go up.

Making Silk Fabric

Graded raw silk is then cleaned and processed so it can become fabric. The first major step in this process is throwing in which the silk fibers are made into yarns. This name derives from the original process in which threads of silk would be thrown over and hooked onto a stationary pin and then twisted around a wheel. Increasing the distance between the pins and the wheel would increase efficiency and quality.

Historically, silk mill workers – usually children – would spool the threads between wheels and pins that could be as much as a hundred feet apart. Today though, this process is done by machines.

Silk mills are located all over the world today, but certain nations, such as France, Italy, and Japan, have developed reputations for making the finest silk textiles that are of the highest quality but also command the highest prices.

Because of all the work that goes into making it, silk fabrics can cost over $100 per yard, and that’s before they’re even made into anything. In turn, silk yarn can become a large variety of silk fabrics from Shantung to Charmeuse.

All of these are graded according to “momme.” And no, that doesn’t mean we’ve asked our mummies what they think of the silk. “Momme” is a Japanese term abbreviated as “mm” that refers to the relative weight of the silk. More specifically, it’s defined as the weight in pounds of a piece of fabric that is 45 inches wide and 100 yards or 3600 inches long, and it’s a common value for assessing silk quality and expense. For reference, this usually means that something like a lightweight silk gauze is anywhere from three to five momme, while heavier silk satins can be up to 30 momme.

Higher momme is achieved with a yarn that is thicker, with a higher ply, or by increasing the density of the threads during weaving. In general, a higher momme is going to respond to higher quality, but, as with other things, the ideal momme is going to correspond to the use of the finished product.

Basically, raw silk is processed into threads, yarns, and fabrics in a variety of weaves and finishes that are then put into different functions. This additional layer of workmanship requires skilled workers and specialized machines.

Making Silk Products

At heritage mills in Europe and Asia that are associated with the highest quality silk fabrics, the fabric itself can go for more than $300 a yard. With all that said, though, what started as a tray of mulberry leaves and a pile of silkworms ends up being a luxurious silk fabric that can be used in any number of different menswear products.

Of course, the menswear pieces that are probably most associated with silk today are neckwear. Colors from the dyes that are applied appear rich and vibrant with clean lines and no bleeding.

Different silk weaves can also produce a variety of different ties; from the more casual Cri de la Soie, literally translating to “cry of the silk,” to the elegant formality of a faille grosgrain black bow tie.

Scarves are another common use of silk in menswear and, like neckwear, they can also be richly colored, but they also help regulate body heat. But, for the ultimate pop of refined color, silk is ideal for pocket squares that can add visual interest and tie an entire outfit together.

Next up, while entirely silk suits might be a little too 18th century for us, silk blends – often with wool or linen – can be excellent choices for modern suits or sport coats. The added silk makes the garments softer overall and also has the added benefit of better temperature regulation. Silk blend shirts also share these qualities and they tend to be especially touchable.

And when speaking of exceptional touchability, sheen, and lustrous color, we’d be remiss not to mention silk in its use for formal evening socks.

For softness, breathability, and appearance silk is also commonly used in traditional sleepwear like pajama sets and dressing gowns. And for more information on sleepwear, you can consult our guide on the subject.

Men’s Classic Pajamas, Slippers, & Robes (Dressing Gowns)

Due to its breathability, silk is also often employed as a lining in bigger garments like coats or jackets to smaller ones like gloves and hats. And, of course, because silk is often used in high-end men’s products, the workmanship that goes into these products also brings up the overall cost.

Also, as a luxury material, silk is often paired with other luxury materials. At Fort Belvedere, for instance, we emphasize the natural brilliance of high-quality silk with madder dyes, which you can find more about here. As you might expect then, combining multiple high-quality materials will also lead to a higher final price.

Pros & Cons of Silk

The upsides of high-quality silk are many then, as it’s going to possess an instantly recognizable gloss, an extremely soft hand that is lustrous and smooth without feeling overly slick, or slippery thermoregulating properties that naturally circulate air for a cooling effect, and that can also help insulate the heat coming off of your body as well as strength, durability, and color fastness.

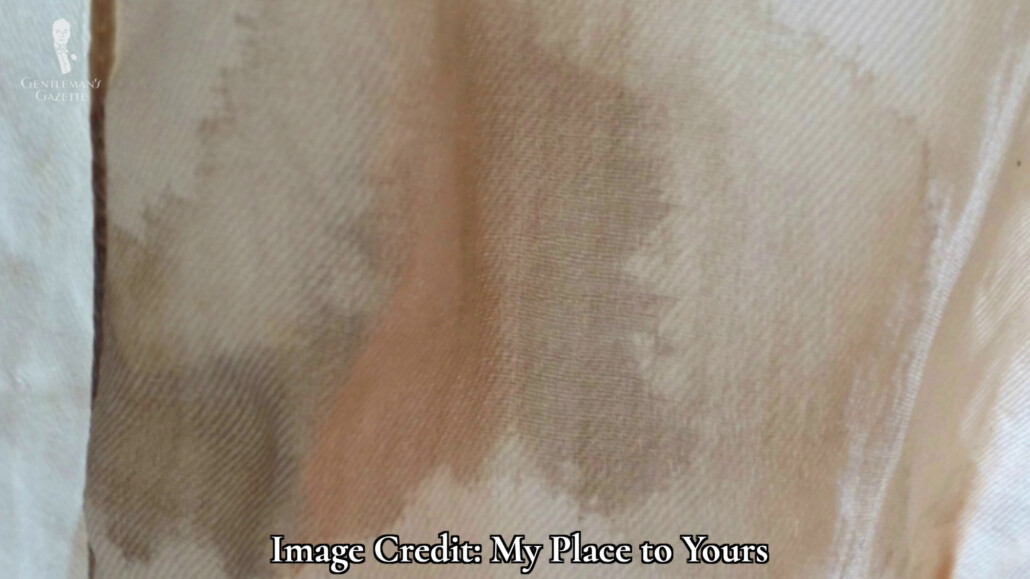

It must be said, though, that silk also has some downsides. While it doesn’t tear easily, silk has poor elasticity, meaning that, if it stretches out, it’s not going to bounce back. Silk linings, for instance, can often be stretched out over years of use, becoming baggy and unappealing.

Silk is also easily marred, meaning that it can be stained, bruised, or lose its texture fairly easily. Even washing can permanently damage the feel and sheen of silk, which is why many silk products need to be carefully hand washed with the right materials or dry cleaned. And speaking only for myself here, the modern ubiquity of satin-polyester and its ability to approximate the look of silk has actually turned me away from real satin-silk.

This is because the distinctive translucent sheen of satin-silk that is shared by satin-polyester proliferates in cheap garments. Therefore, in recent years, I’ve found myself avoiding satin-silk in various products, preferring other treatments and weaves like madder or grosgrain. Your mileage may vary here, of course, but it’s something to consider.

So, why is silk so expensive?

In conclusion, then, silk is so expensive for a number of reasons. First, it must be harvested from animals that require care and feeding in a process that is both time and resource intensive. Next, it must be specially woven and prepared from a limited supply of raw materials, then it has to be assembled into a final product that requires skilled workmanship to ensure no mistakes and minimal waste.

Essentially, silk requires a process that is almost as exhausting and fraught as traveling those old 4,000 miles of the original Silk Road, and it has a price to match. And with that, we hope that we’ve unraveled just why silk is so expensive.

Outfit Rundown

Today, I am, of course, wearing several different garments and accessories that incorporate silk. First is my double-breasted sport coat in tones of blue with a checked pattern. That’s a blend of 85% wool, 10% silk, and 5% linen.

I’m wearing it over a French-cuffed shirt that incorporates a micro grid pattern of blue and pink on a white ground. Into those French cuffs, I have inserted our platinum-plated, sterling silver eagle claw cufflinks from Fort Belvedere with red carnelian as the stone to bring out those warm tones.

My trousers are in gray and also feature a micro check pattern to harmonize with the jacket and the shirt.

My shoes are cap-toe Oxfords from Beckett Simonon in a dark reddish color that also harmonizes with the other red and pink tones in my outfit.

My vintage bow tie is 100% silk, and it’s in a repeating micro pattern featuring tones of red, blue, green, and orange.

My remaining accessories are also from Fort Belvedere today, and these would include my two-tone, shadow-stripe socks in pink and gray, my mini dark red carnation boutonniere, and my pocket square, which is in a silk-wool blend in colors of beige, blue, green, and pink in a paisley pattern with a beige shoestring edge. Specifically, this blend is 70% silk for luster and color and 30% wool for body.

And, of course, you can find all of the Fort Belvedere accessories I’m wearing today, as well as a wide array of other men’s accessories, many of them made from silk, by visiting the Fort Belvedere shop.

Silk is much more affordable when you buy it second hand. Silk sport coat-$10.00, Silk ties-$1.00 to $3.00 each. I’ll let the ones with money buy them new. I’m content with quality used silk.

A man after my own wardrobe.

This is a wonderful article, Preston! very well done!

Most of the two dozen Hawaiian silk shirts I have are made in China and the weight of the fabric does vary with the heaviest being the most luxurious, in my opinion. The pattern continues across the placket and the buttons are made of coconut shell. Some have chest pockets but about half have no chest pocket. I feel that I may be a bit of a snob regarding my Hawaiian shirts, but I actually have a few made of polyester and fabric blends. While I do refer to my casual shirts as Hawaiian, the best of the lot come to me via the Caribbean, not the Pacific Rim.

Great enjoyable and informative article, thank you!

I tried an Eton pure silk shirt, which is beautiful material and very well made. However, the softness of the fabric also affects the way the shirt wears and sticks in my trousers. I did not like the excess cloth on my waistband.

Silk blend in shifts and jackets are great.

Great article, indeed!

Thank you for this fascinating video. I appreciate the great amount of research that went into this article! It certainly gives me an appreciation for the silk accessories available to us. Two silk worms decided to race…but it ended in a tie.