Even today, the English Drape cut is a highly discussed silhouette. While some gentleman praise the comfort and ease of movement of the drape cut, and thus swear by it, others detest its silhouette, much preferring a “clean” line.

It is often said that the Dutch tailor, Frederick Scholte, invented the drape style, though whether he was, in fact, the inventor is disputed. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on the nature of this style rather than the origins of drape using illustrations of the English Drape & the London Lounge Drape.

What is the English Drape cut?

First of all, the expression “drape” derives from the French word “drap,” which simply means “cloth”. In a nutshell, drape describes the manner in which the fabric of a garment hangs from the shoulders and the waistline.

The English Drape cut is a style for single breasted and double breasted jackets or topcoats featuring fullness across the chest, forming vertical wrinkles, as well as over the shoulder blades.

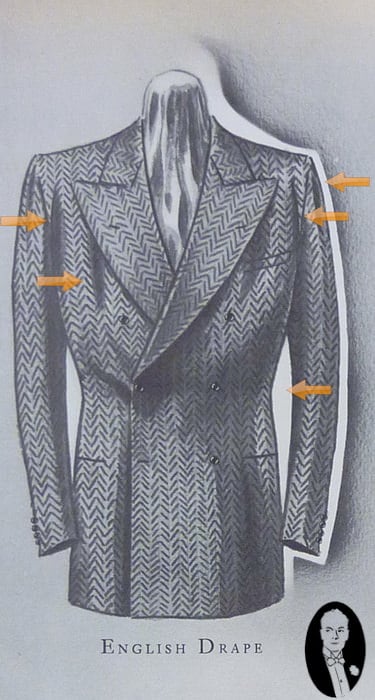

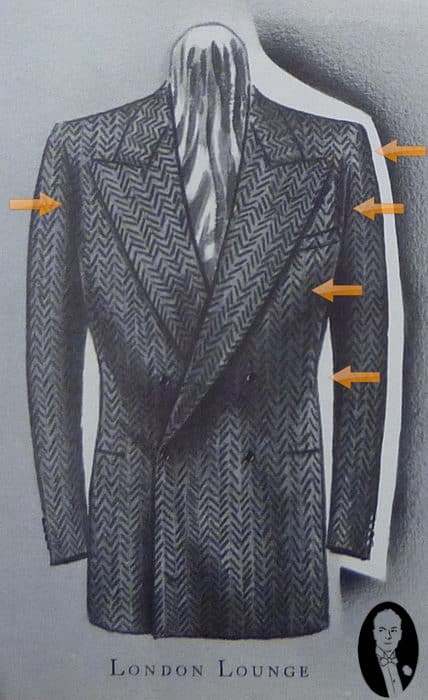

Here you can see two examples from Apparel Arts in 1935:

1. The American interpretation of the English Drape (click to enlarge):

Note that the jacket has wide shoulders, wrinkles in the sleevehead, fullness of cut and vertical wrinkles in the chest. A very tapered waist makes the chest look even bigger and creates a flared skirt line.

2. A less wrinkly version of the English Drape referred to as London (click to enlarge):

By comparison, this jacket has no wrinkles in the sleevehead, some fullness in the chest with one clean wrinkle next to the scye (armhole), and a lower buttoning point. The waist is less suppressed, which results in a straighter skirt line.

The following is a very interesting article about the introduction of the drape to the US from Apparel Arts, which was published in 1932. It emphasizes its revenue potential to haberdashers, while mentioning some potential difficulties. Being so radically different due to its fullness and vertical wrinkles, AA was well aware that it would be difficult to sell the English Drape style initially, since the male customer had yet to understand this cut. Utilizing a strategy not too dissimilar from modern techniques, their solution was: sell it to women first and men will follow soon after!

Article – Apparel Arts 1932

First major model change in ten years … it arrives marked “handle with care”

When “Johnnie came marching home again”, in the spring of 1919, he came back to find himself confronted, in every clothing store he entered, by suits that were to him exactly like the proverbial red flag to the bull.

Waist-seam suits, curious phenomena of the clothing designers’ unduly sensitive reaction to the spirit of “keep the home fires burning”, hung on every clothier’s racks, stiff and martial in their lines, hatefully reminiscent of so many insolent and overbearing second lieutenants marching on parade. The reaction of the war-weary male was immediate, complete, and wholly natural revulsion, and the masculine silhouette underwent a sudden and total change.

Trousers had been tight—they immediately widened. Waistlines had been emphasized—they immediately disappeared. Patch-pockets had been in—they immediately went out. Fancy backs had been common—they immediately became as rare as horse-cars. Fashion changed.

With the disappearance of the last vestige of military influence from men’s clothing design, a loose ultra-civilian type of suit model came in.

It was everything that the clothes of the war period were not and, it must be recorded that it was a change for the better, much better from the standpoint of taste as well as comfort. But men’s suit models then and there settled into a rut from which it began to appear that they might never emerge. For from that day to this, change has been confined to such comparatively minor details as raising and lowering the gorge, lessening and increasing the space between button holes, dulling and sharpening the points of the lapels.

Since then, because of the very slight changes in the fundamentals of design, men have been less inclined to buy new suits simply because, but only when their old ones were worn out. Thus the men’s clothing industry has been in a long decline. For there has been nothing to accelerate suit buying, even when times were good, other than price, pattern, and color—all three very weak as compared to the slate wiping effect of a sudden and complete model change.

The war ended the age of style and inaugurated the age of fashion. That was not apparent at the time, but its truth has become increasingly evident every year since. In other words, the days when manufacturers could with impunity “put over a style,” in disregard of the trend of authentic fashion, were really at an end the moment the period of post-war disenchantment began. Some manufacturers learned the lesson soon, others late, but all learned it, some with greater sorrow than others, as the years rolled by. Fashion, for men, became concerned with minutiae of accessories and embellishments, brooking no change in the basic structure of “coat, vest, and pants”, in which sales, most naturally, lagged behind.

Now, for the first time in these more than ten years, a basic model change is beginning to make its appearance. It has become known, for want of a better name, by the somewhat inaccurate designation, “draped clothing.” It is a model that has been employed by the best custom tailors for a number of years, but it has been slow in coming over into the ranks of ready to wear. It is sufficiently different from the existing mass popular type of suit that the average man has been very slow in gaining any understanding of it. In fact, in the instances where its introduction has first been attempted, the average customer, not understanding its basic design, has complained that it didn’t fit him and set up a yell for alterations as soon as his image confronted him in the mirror.

This reaction, on the part of the average customer, upon making the acquaintance of draped clothing for the first time, must be accepted calmly as “one of the hazards of the course.” The draped coat is chesty and waisted. An integral part of its “expression” is given by the vertical creases, or breaks, of the front from sleeve head to arm pit, and the customer, thinking that the ideal suit ought to fit like wall paper, can’t understand these creases at all. The break at the waistline is not beyond his comprehension, but the breaks in the front seem to him to constitute simply a job for the bushelman. If the customer is accompanied by a woman, she, too, may fail to understand what this business of “drape” is all about.

Women, who expect their own garments to be molded to the figure, will, indeed, be inclined to talk against the new draped clothing on the assumption that it is simply a poor fit. Exploitation of the new model affords a rare opportunity, but it is an opportunity that is fraught with danger. Draped clothing must be sold on an entirely new basis. That is the danger—and that is the big advantage. It offers a chance to wipe the slate clean—to batter down all the old conceptions—to make men realize that they need new suits now, not because the old ones are worn out, not because there is lofty economic patriotism in a “buy now” decision, but because, at last, the time has come when one’s old suits are “dated” by something more than wear.

Pundits have long belabored the question “what’s wrong with men’s apparel advertising?” It seems to have occurred only to a slim minority of them that perhaps the biggest thing wrong is the apparel itself—in other words, the lack of real “news value” in the merchandise itself. The deadly monotony of men’s suits, one season after another, has forced the advertising message to wander away from the merchandise itself, in search of something stimulating to talk about. Draped clothing terminates that situation.

As an advertising theme, if nothing else, it is a god-send. It needs intelligent advertising, it is true, but it makes intelligent advertising easier than it has been for a long time. It calls for educational copy. And the time is ripe for it. The conception of draped clothing has begun to trickle into the mass consciousness to a sufficient degree already, that if you are to catch this new fashion on its up-bounce you must begin to exploit it now. A Chesterfield ad appearing early in March was illustrated with a photograph of a man wearing an almost perfect example of the draped suit. That is significant—it means that the fashion is no longer considered too esoteric for mass appreciation.

Sell the women first. Get it across to them that there is a basic change of silhouette in men’s costume, as complete and as mattering to the average figure as the change that has come about in their own fashions.

Tell them that it is no longer fashionable for men’s clothes to fit snugly—that a man’s suit should break at the shoulders and should “bell” somewhat in the chest, pulling in at the waist -and that suits that don’t do that are as out of date (almost) as the clothes that Abe Lincoln wears on the statue in the Park. (You can tell a woman that it is smart to wear gloves a size or so too large, in some particular season, and she will believe you and without a qualm will junk perfectly good pairs of gloves that fit her, to go out and buy new pairs that don’t. That’s been proved.) And drop a hint that the draped suit makes the ex-athlete’s now thickening torso look considerably less conspicuous. You’ll be making headway—almost overnight.

That’d work today as well, considering how many women shop for men.