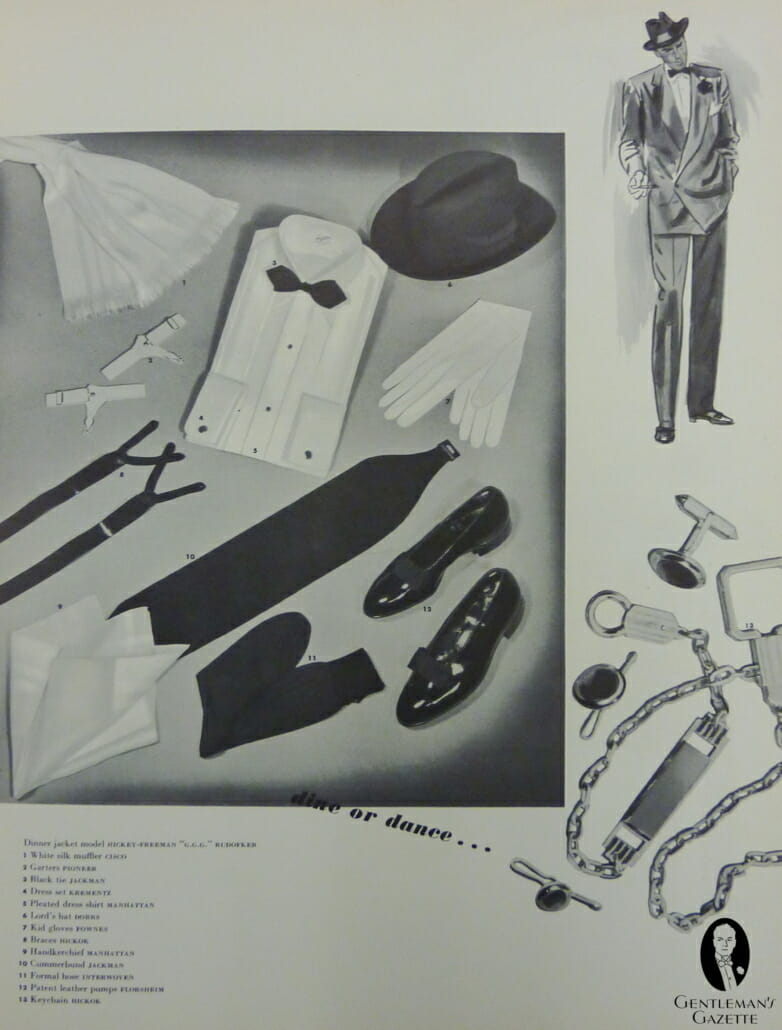

It is often said that “the devil is in the details,” and that is certainly true when it comes to evening accessories. In this section, you will learn about how Black Tie accessories developed, which will you give you the context to make the best possible decisions when assembling your own accessories.

- Evening Jewelry Through the Ages

- Stellar Studs and Classic Cufflinks from the Victorian Era to the Present

- Fobs and Watch Chains: The Decline of a Giant

- Key Chains: Unusual Accessories of Another Age

- The Wristwatch: Timeless Timepiece

- Evening Dress Gloves: 19th Century Ascendancy & 20th Century Decline

- Formal Facts

Evening Jewelry Through the Ages

Stellar Studs and Classic Cufflinks from the Victorian Era to the Present

The Victorian Era

Cufflinks and studs came into fashion in the 1840s along with starched shirt fronts that were too difficult to button. Early and mid-Victorian etiquette authorities cautioned that they be used judiciously to avoid lapsing into vulgarity. More specifically, evening jewelry was to be of maximum quality and of minimum quantity and flash. For studs and cufflinks, this typically meant simple gold designs although there are some period references to studs of diamond, black pearl, opal, and amethyst.

The rules remained the same in the late Victorian era. “No jewelry whatever is used,” dictated an 1887 American conduct manual, “except that which has a direct purpose and this is kept as simple as possible.” For the author, this specifically meant studs and links of modest size and non-lustrous finish although he allowed that a single shirt stud could be larger than studs worn as a pair. Gold continued to be the most popular option but pearl and white enamel settings also came into play during this time. The arrival of the dinner jacket in the 1880s had little impact on these trends as it was simply a substitute for the full-dress tailcoat and not the basis of a distinct outfit.

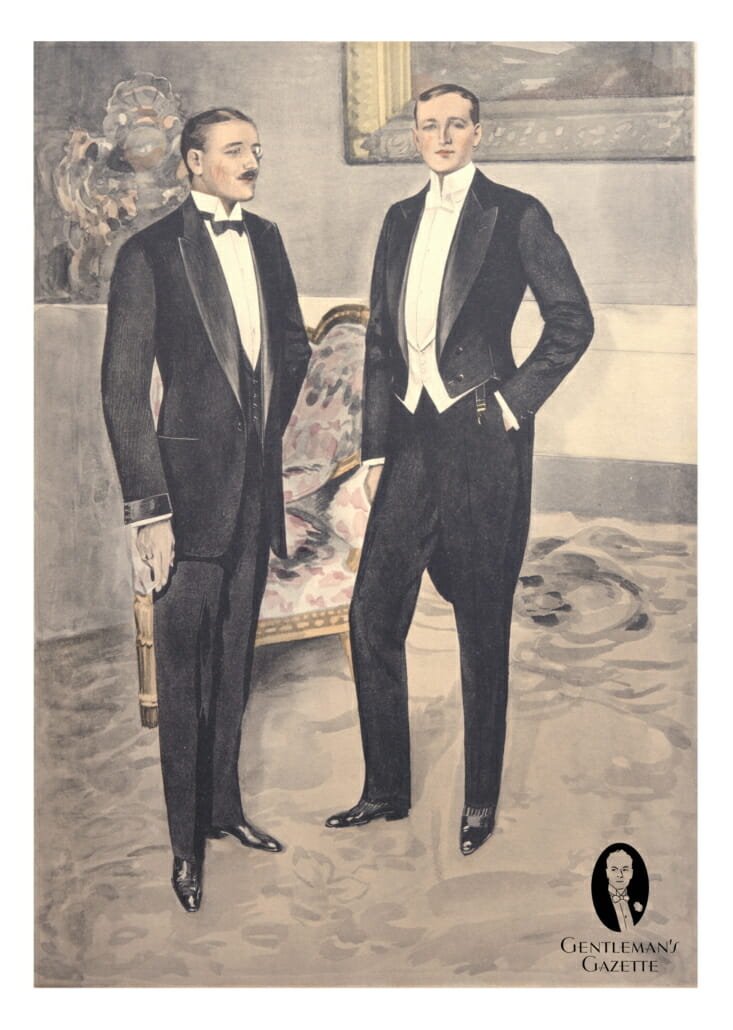

The Edwardian Era

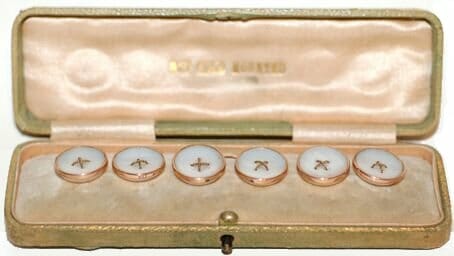

Full dress in the Edwardian period continued to be decorated with gold, pearl and white enamel cufflinks and studs for shirts and waistcoats while some trendier dressers opted for mother-of-pearl, stonine or moonstone variations. Gold jewelry was also common with the Edwardian dinner jacket but the informal coat’s burgeoning popularity gave rise to some unique alternatives in the form of semi-precious stones and dark enamel.

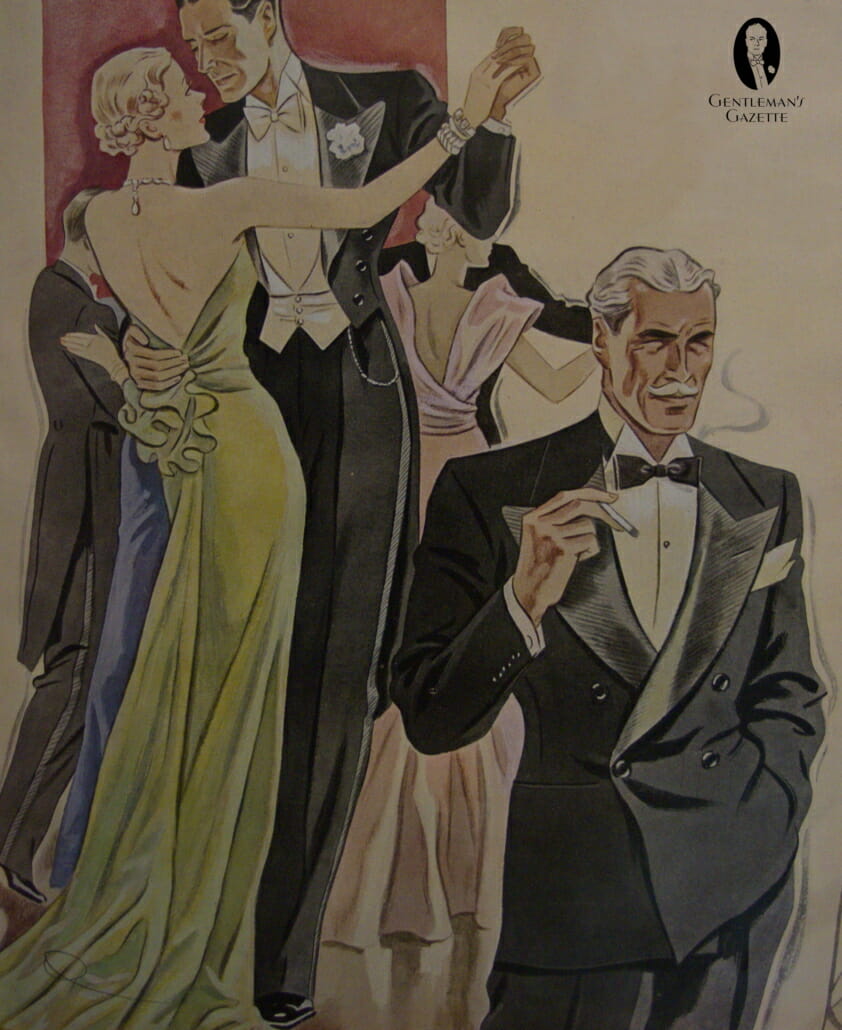

The Interwar Years

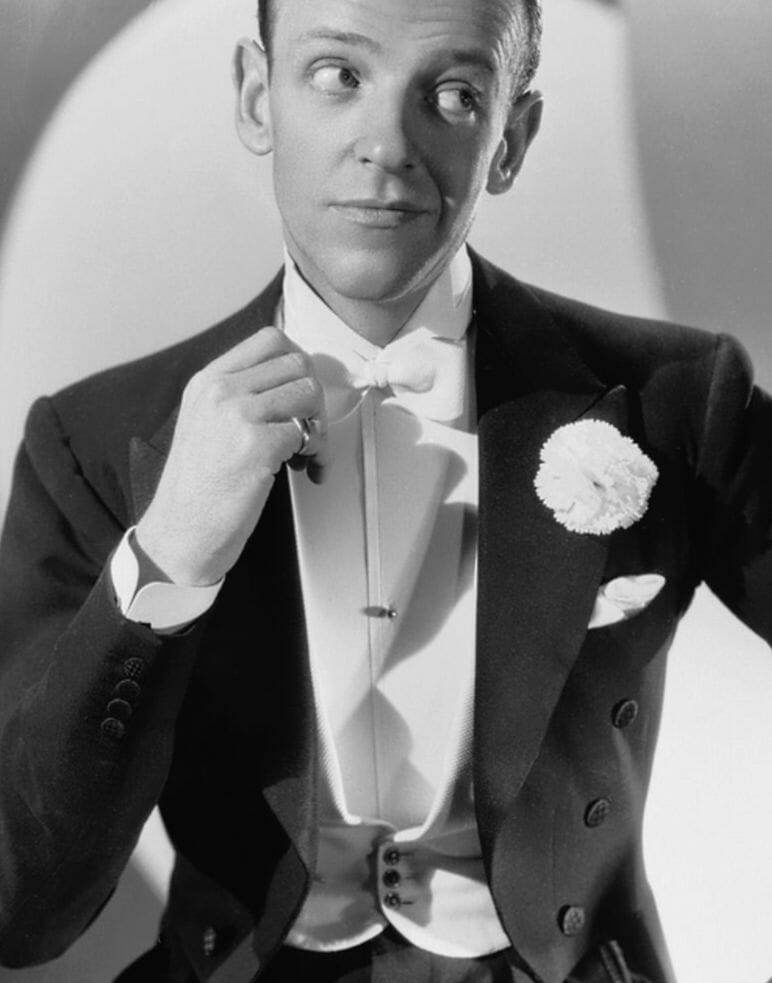

At the beginning of the interwar period, pearl and semiprecious stones were the most popular choices for full-dress jewelry The pearl option became ever more standard throughout the 1930s establishing a preference for ornamentation that would subtly blend with a man’s white dress linens. Other variations included enamel, rock crystal, and mother-of-pearl which could sometimes be black. Contrasting black stonine waistcoat studs were a fad in the 1930s thanks to their adoption by the dandy Prince of Wales and led some mavericks to experiment with dark-colored alternatives. Emily Post books of this time recommended sets of platinum or white gold.

With black-tie attire, the settings of choice were pearl, mother-of-pearl, jewels or enamel although black options such as onyx or black enamel became increasingly popular towards the start of the Second World War. Gold cufflinks were also mentioned occasionally for wear with dinner jackets. (Sources did not specify yellow or white gold but typically the former was understood whenever the term was used generically.)

As to the materials that held the decorative pieces in place, evidence suggests that platinum was popular along with white gold and “white metal”. Bezels of yellow gold seem rare and silver rarer still.

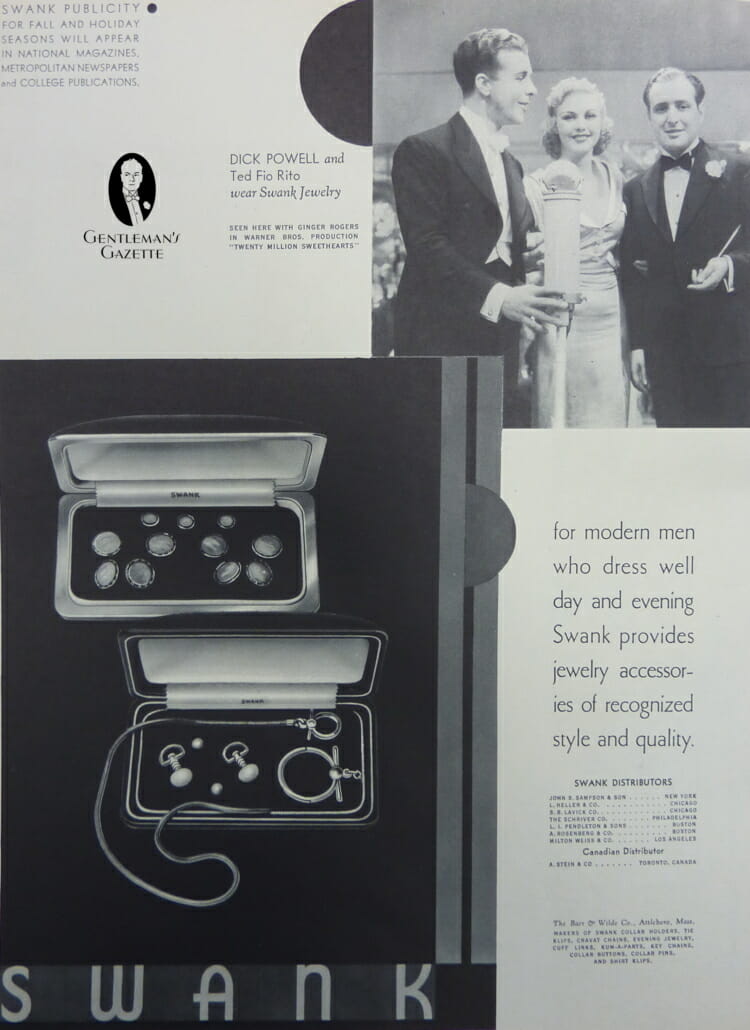

Whether full-dress or semi-formal, it became increasingly de rigueur for evening jewelry to be worn as a matching set with one ad by U.S. jewelry maker Krementz insisting that such uniformity was “absolutely essential”. The same company also offered collar studs of 14 karat solid gold, a truly decadent touch considering that these hidden fasteners would never be seen by anyone but the wearer.

The advent of the warm-weather black tie in the early ‘30s encouraged alternatives to the conventional inconspicuousness of evening jewelry in America. Reds, blues and greens that had first appeared alongside the informal new white dinner jacket became more prominent in dress sets as the decade progressed. Colored stones were especially popular in cufflinks and when worn with white jackets they would often match the tie and cummerbund. For men who could not afford real rubies, emeralds and sapphires there were substitutes ranging from plain glass to the more expensive synthetic stones.

The War & Post-War Years

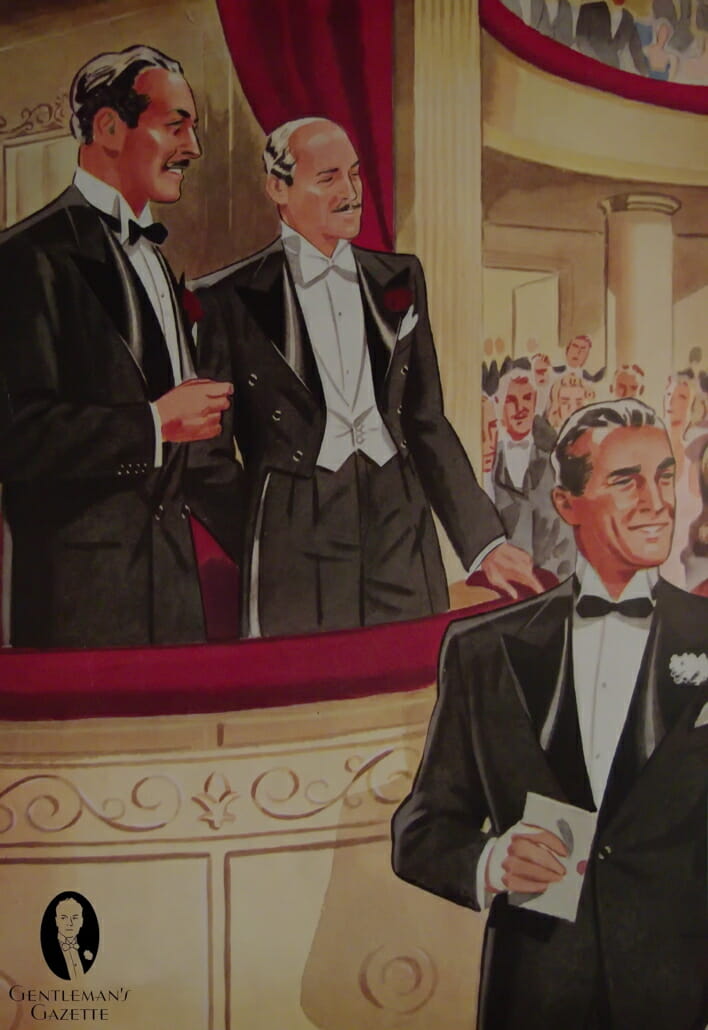

World War Two brought an end to the Depression-era’s sartorial panache and in the modern era that followed pearl was the most popular choice for white-tie jewelry followed by gold and platinum and, less commonly, white gold and mother-of-pearl. For black tie, etiquette authorities usually prescribed pearl and mother-of-pearl and sometimes onyx. Fashion sources were a little more liberal in recommending dark pearl, gold, enamel or colored stone. Whatever the choice it remained the norm for all pieces to match.

By the mid-1960s pearl and mother-of-pearl became pretty much the norm for white tie. Black-tie jewelry remained an “anything goes” proposition until the 1970s when gold and onyx became increasingly standard.

While old shirt studs are often beautiful, they are simply too small for modern day evening shirts, which means your shirt pops open when you wear them during the evening. If you want to prevent that you have to get modern day evening shirt studs.

Fobs and Watch Chains: The Decline of a Giant

According to this comprehensive guide to pocket watches and chains, the mid-17th century marks the point when the English began to wear their timepieces in small “fob” pockets sewn either inside the waistband of their breeches or on the outside of their waistcoats.

When worn in the waistcoat pocket, the watch was attached to a watch chain. When worn in the breeches pocket, the watch was attached to a fob (named after the pocket) which was a strip of fancy fabric that hung outside the waistband and was weighted down with an antique wax seal (a small metal stamp that imprinted a mark into the wax that was used to seal envelopes) or some other personal memento.

During the Regency era, it appears that the waistband option was preferred to the waistcoat option. Then as timepieces became thinner the practice of wearing them in the waistcoat pocket became the norm and was championed by Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert who also introduced the styles of watch chain named after him. The “single Albert” chain was connected to the pocket watch at one end and the other end was attached to a waistcoat button thus creating a single “U” of draped chain between the pocket and button. The “double Albert” chain did not attach to the waistcoat but instead passed through one of its buttonholes (or a purpose-made hole) and was attached to a second object kept in the other waistcoat pocket, thus doubling the number of “U”s created by the draped chain. With this style, there was often a very short piece of additional chain attached to the main chain at the buttonhole which would be used to carry a watch key or another personal memento.

Period etiquette guides reveal that by the mid-Victorian era pocket watches were being worn with evening waistcoats in the same manner as with day wear. However, the drapes of thick chain and numerous dangling appendages were not harmonious with understated evening finery and the practice pretty much died out by the end of the century. In 1901 the American conduct guide Etiquette for All Occasions remarked on the watch chain having become unpopular with young men and said that it was worn by older men only “if the links are small and the whole effect very inconspicuous.”

Meanwhile, the fob continued to appear with evening wear until it fell out of favor after World War I. It later made a brief resurgence with full dress around 1939 as part of that period’s return to Edwardian formal tradition. Said Esquire in January 1940, “The old-fashioned Georgian seal watch fob has returned, and is worn on the left side for convenience”.

Key Chains: Unusual Accessories of Another Age

At the turn of the century, there appeared an alternative method for storing the watch in one’s evening trousers: the fine-link keychain. Etiquette for All Occasions described this option in detail in 1901:

The watch is attached to a gold key-chain and concealed in the pocket. The chain is attached to the suspender or two chains are worn – from one hangs the watch, from the other the keys; the greater portion of the chains and their appendages are concealed in a trouser pocket.

The keychain became very popular with evening wear in the 1930s and remained so through the forties.

The Wristwatch: Timeless Timepiece

In the early 1950s, the pocket watch began to lose ground to the wristwatch which had been introduced to daywear after the First World War. Amy Vanderbilt’s 1952 Complete Book of Etiquette describes the former option and its accessories at the twilight of their popularity:

Wristwatches, unless of delicate design and without a leather strap, are less likely to be worn with evening clothes. Instead, a thin watch, in gold or platinum, on a thin gold or platinum chain (or grandfather’s good gold chain, which may be monumental but impressive) is worn. If any ill-advised woman should try to give a man a platinum chain with tiny diamonds between the links, he should return it to the jeweler who was talking into making it and go to Palm Beach on the proceeds or put them on the nearest fast horse.

Evening Dress Gloves: 19th Century Ascendancy & 20th Century Decline

Nineteenth-century etiquette manuals reveal that the practice of dressing one’s hands was partly a matter of aesthetics – “nothing can give a more perfect finish to a handsome dress than the covering for the hands” says an 1830 guide – as well as a more profound matter of social propriety. From The Handbook of the Man of Fashion:

Among trivial matters, nothing, perhaps more often distinguishes a gentleman from a plebeian, than the wearing of gloves. A gentleman has worn them so constantly from his earliest years, that he feels uncomfortable without them in the street, and he never suffers his hands to be bare for a moment; a vulgar person, on the contrary, finds himself incommoded by a warmth and confinement to which he is unaccustomed, and even if, in compliance with usage, he has supplied himself with what he deems unworthy of the expense, he will do no more than swing them between his fingers, or wrap them around his thumb. It is not enough that you carry gloves, you should wear them . . . The ungloved hand is the cloven foot of vulgarity.

Glove Materials

Dress gloves for both indoor and outdoor use were generally constructed from the hides of antlered animals and the quality of the leather reflected the formality of the occasion. The most basic of these leathers were buckskin and doeskin made from male or female deer respectively, and chamois (pronounced SHAM-wa, or, parochially, SHAM-ee) from the goat-antelope of the same name. The best gloves were made from various goat hides prized for their thinness and softness. This category included capeskin aka cape from the goats native to the Cape of Good Hope, and kidskin or kid from young goats. The latter was the lightest, strongest and most flexible of all, producing an effect poetically described by The Whole Art of Dress:

Kid of all materials is, without exception, the most beautiful, and sits best on the hand, from its exceeding pliability (when good); compressing the hand with a gentle pressure, like a second natural skin over the first.

While silk was sometimes used for full-dress gloves in the early century, by the 1840s kidskin was the preferred choice for wear with one’s evening finery. At first, the favored colors were tan and yellow but white became predominant around 1815.

Glove Colors

As the century progressed, acceptable colors expanded to include pearl, light grey and light yellow, the latter hue often referred to as buff. However, these were recommended only for less formal occasions and white remained de rigueur for balls and the like; in fact, one book explained that glove hue was the sole difference between ball dress and ordinary evening dress. Lavender is mentioned in some circa 1860 etiquette sources but only in the context of being discouraged. In all cases, gloves were expected to be worn throughout the evening with the notable exception of dining because, after all, “nothing is more preposterous than to eat in gloves.” They were also to be “faultlessly fitting” as well as pristinely clean. A common suggestion for maintaining cleanliness over the course of an evening spent touching ladies’ dark dresses or handling refreshments was to carry a spare pair.

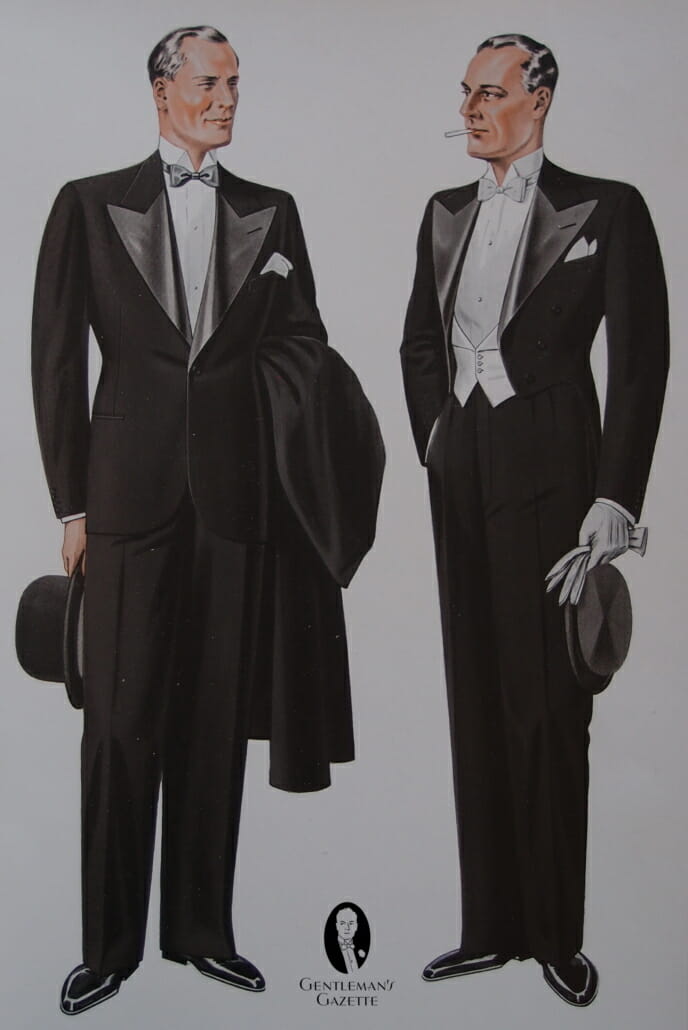

The Slow Decline in Popularity

By the late Victorian era, it was becoming acceptable to appear barehanded at less formal evening affairs. However, gloves remained obligatory at balls and the opera. In the case of the former, the rule was partly a matter of respectability as dancing involved physical contact with the fairer sex and “to touch the pure glove of a lady with uncovered fingers is – impertinent!” Contrasting black stitching was a vogue at the end of the century.

In the Edwardian era, the glossy glacé finish was popular on full-dress gloves which continued to be worn for the most formal of occasions. As for gloves appropriate for the informal new dinner jacket, many etiquette guides said nothing on the subject while the others offered up a wide variety of recommendations. Grey suede was the most popular suggestion but there were also references to white and tan colors. Sanctioned materials ranged from deerskin to chamois to reindeer to mocha (goatskin with a suede-like finish). To allow a snug fit at the wrist, the bottom of the gloves were slit and fastened with one or two buttons or clasps that were sometimes described as “patent”.

The lowering of social standards brought about by World War One meant that full-dress dress gloves became limited mostly to balls and ushers at formal weddings. White kid was still the most popular version and white mocha still a common alternative. For black tie, the preferred options were white or grey, usually in buckskin. However, many published authorities remained silent on the topic and Emily Post books specifically prohibited the wearing of gloves with a tuxedo.

Formality was struck another blow by World War Two, with etiquette maven Amy Vanderbilt noting in 1952 that “today the white kid gloves, ultra-correct for indoor wear with formal clothes, are seldom seen, although some fastidious men don them for dancing, to avoid having to place a moist hand on a woman’s bare back.” Grey continued to be the dominant choice for black-tie dress gloves, either in mocha, chamois or buckskin. These trends remained largely unchanged until the 1990s at which point etiquette and sartorial authorities ceased including gloves in their descriptions of evening wear. Notably, one of the last such references recommended that for white-tie affairs the gloves simply be held in the left hand, a complete reversal of the original proscription of this practice.

Formal Facts

Stud Mechanics

The spring-back style of cufflink was patented in 1890 by Larter and Sons. The thinner half of the backing is pushed into the thicker half to create a J-shaped backing that is slipped through the shirt’s buttonhole. Once let go the backing springs back to full length.

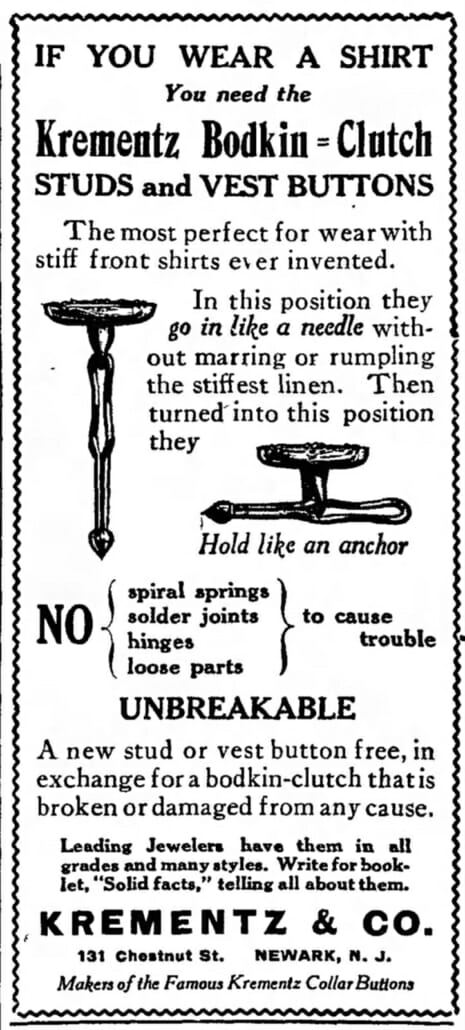

Larter contemporary Krementz patented their “bodkin-clutch” construction shown in this 1911 ad.

The fixed-back style of stud most common today originated in the mid-1930s and can also sometimes be found in a screw-back variation. However, the small size of these round backs can potentially slip through the button hole and require the back (or the front) to be squeezed through the shirt’s small buttonhole likely wrinkling the stiff shirt front during the process.

Some stiff-front shirts are designed with a side slit that allows the wearer to adjust the studs under the shirt without creasing its starched bosom.

Formal Facts: Studs versus Buttons

The term “button” was often used in reference to shirt studs, waistcoat studs and even cufflinks during the 19th century. Adding to the confusion, studs were also often styled to resemble ordinary buttons.

Interestingly, the 1948 Vogue’s Book of Etiquetteclaimed that “studs are worn only on stiff evening shirts” and that soft ones should use regular buttons. No other vintage etiquette or fashion authority made this claim though.

Antique Timepieces on Ebay

To see a pictorial summary of all the pocket watches, fobs and chains currently available on eBay check out the Collectors Weekly site.

Explore this chapter: 8 Vintage Evening Wear

- 8.1 Vintage Black Tie Etiquette & Dress Codes

- 8.2 Vintage Tailcoats & Tuxedos

- 8.3 Vintage Evening Waistcoats & Cummerbunds

- 8.4 Vintage Evening Shirts

- 8.5 Vintage Evening Neckwear

- 8.6 Vintage Evening Footwear

- 8.7 Vintage Evening Accessories

- 8.8 Vintage Evening Outerwear

- 8.9 Vintage Warm-Weather Evening Wear

- 8.10 Vintage Evening Weddings

- 8.11 Retro Evening Wear