The evening shirt has come a long way from its origins as an elongated, ruffled pull-over garment associated with the glittering courts of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Read on to learn more about the history of the evening shirt and observe its many evolution.

Ruffled Evening Shirts of the Regency Era

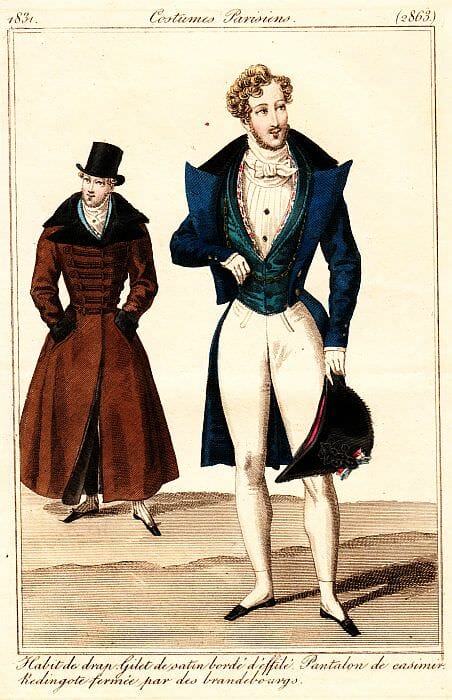

In the early nineteenth century, day and evening shirts were constructed like nightshirts that slipped over the head and were generally made of white muslin (a loosely woven cotton). While the choice of white material might seem entirely unremarkable today, back then the wearing of white shirts, waistcoats and neckcloths was a subtle indication of a man’s wealth. In order to maintain a spotless appearance in the dirty conditions of the country or city these easily-soiled linens would have to be changed frequently which meant hefty laundering charges affordable only by the rich.

The fronts of evening shirts were pleated and/or frilled, often asymmetrically. The Whole Art of Dress published in 1830 suggested a prudent way to incorporate linen’s resistance to wear and yellowing without sacrificing the benefits of cotton:

As the wristbands, collars, and fronts are the only parts displayed in public, it is by no means absolutely requisite . . . to have the body and sleeves composed of linen. On the contrary, fine India long cloth [plain cotton cloth], while it saves an immense expense (one-third the price of linen), is infinitely superior from the coolness and comfort of its wear.

Collars on these shirts were tall enough to stand above the elaborate cravats that swathed the neck during this period and were sometimes stiffened. At first, they were attached to the shirts then in the 1820s the option of detachable collars became available.

Stiff Fronts & Collars for Victorian Evening Shirts

Stiff-Front Shirts

The popularity of lavishly ruffled shirt fronts declined throughout the conservative Victorian era in favor of delicate pleats or a plain front, the latter option becoming the most common style by the 1850s. Plain fronts required a thick bosom to maintain an unrumpled appearance on a shirt that otherwise fit very loosely. Eyelets began to appear at the same time to accommodate studs while starched cuffs made cufflinks more fashionable.

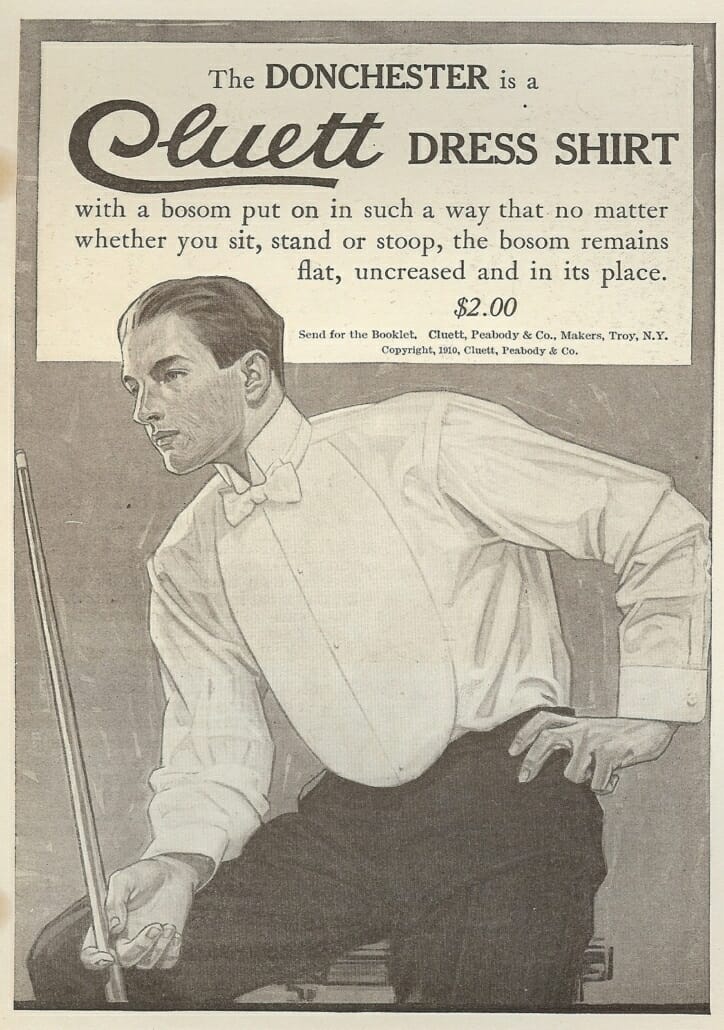

The late Victorian period ushered in the stiff evening shirt that is still the standard for full dress today. It became known colloquially as a “boiled shirt” because boiling was the most effective washing process to keep shirts white and to remove the copious amount of starch from the garment’s four-layer bosom. These bosoms were made of white piqué or linen, the latter either plain or pleated, and generally took one or two studs.

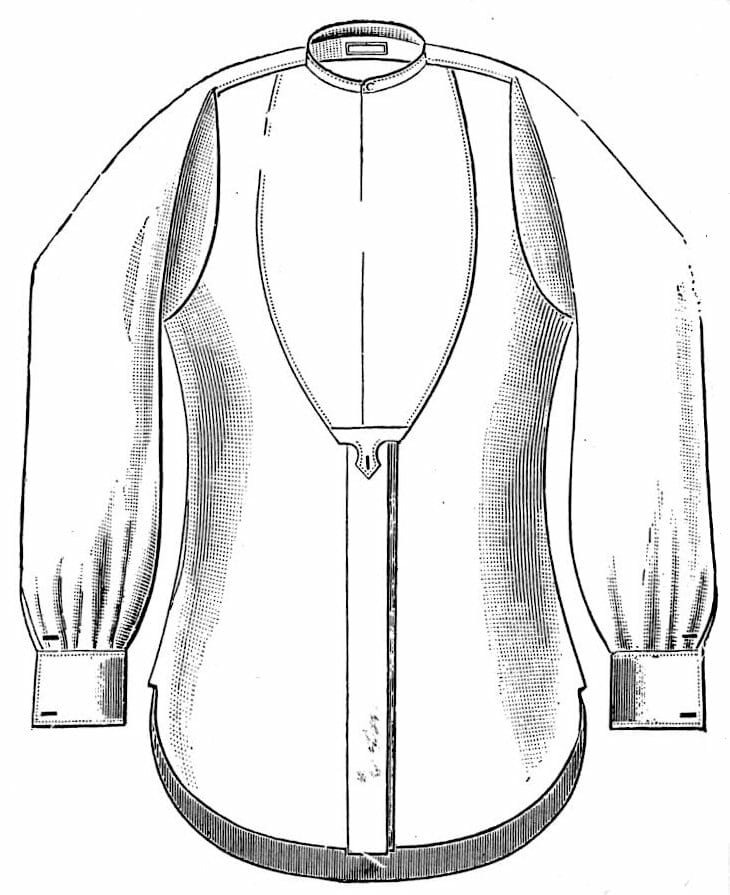

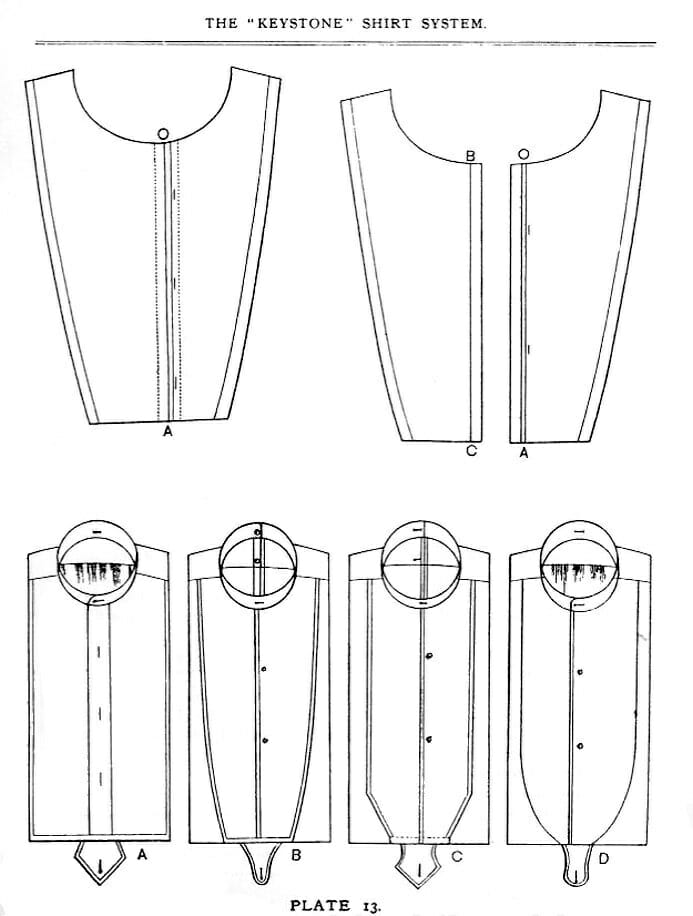

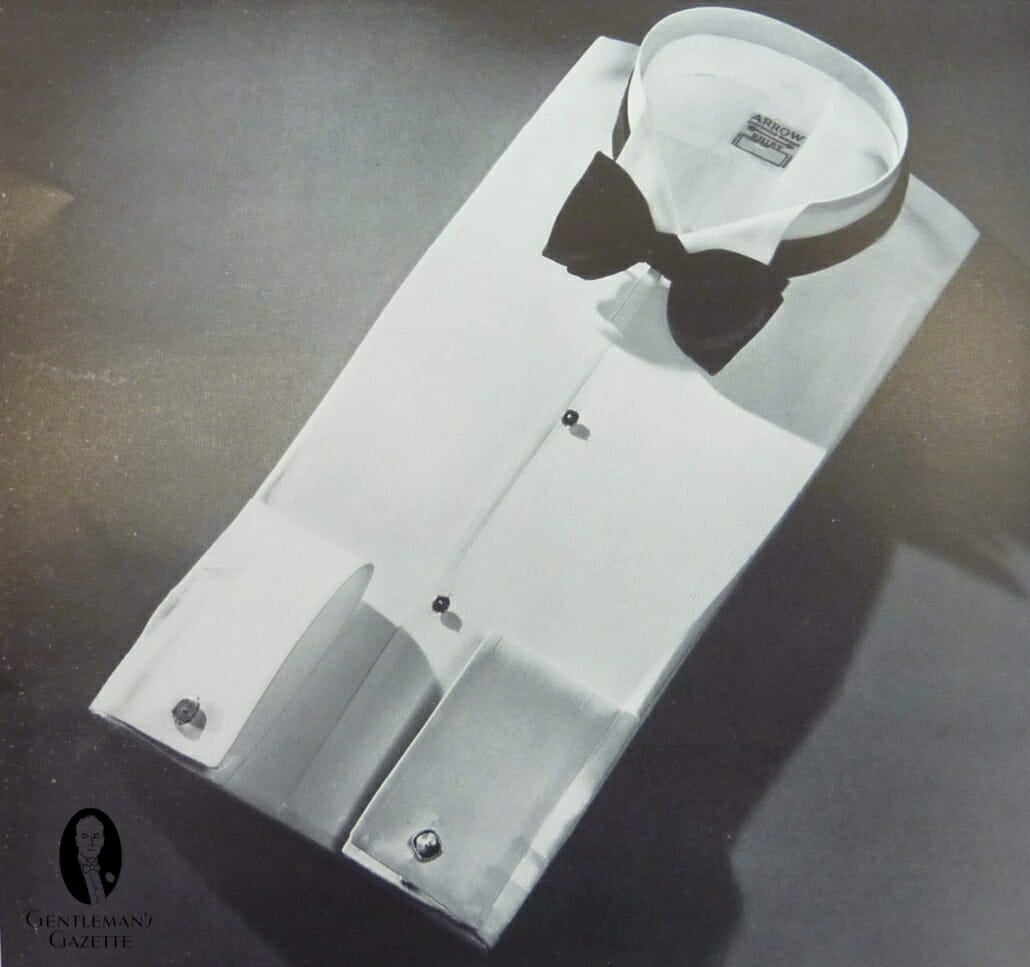

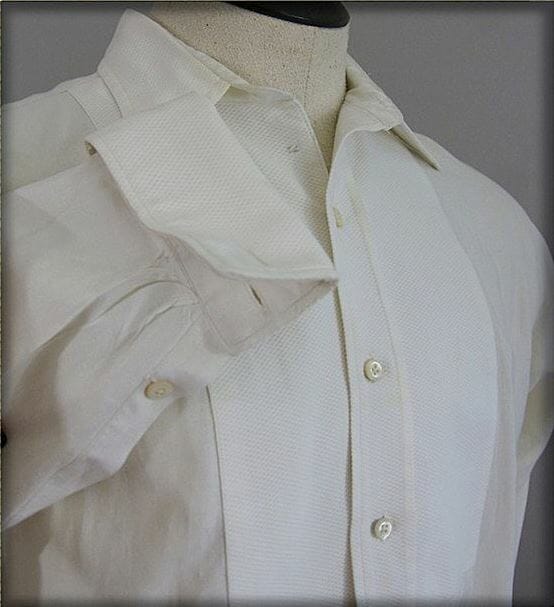

Open-front shirts (aka coat-front shirts) were introduced to menswear in the 1880s to allow for a tapered waist that was not possible in shirts that had to be wide enough to slip over the wearer’s shoulders.

Shirts that opened in the back were introduced in the following decade and this style grew in popularity for dress shirts until it was the predominant choice in the 1930s. They were preferred because their fused bosom would stay perfectly smooth during wearing, unlike open-front versions where the two halves of the bosom were held together by studs and were consequently prone to buckling and billowing. (In open-back models the studs were purely decorative.) The fact that this style of dress shirt was manufactured into the 1960s attests to its effectiveness.

Collars were still mostly tall and elaborately wrapped in neckcloths up to the 1850s. By the 1860s such cravats had fallen out of fashion in favor of the bow tie prompting collars to become shorter as well as stiffer in order to stand upright on their own. In the following decade, collars began to display folded tips called wings. Turndown collars were occasionally seen in the 1860s and early ’70s.

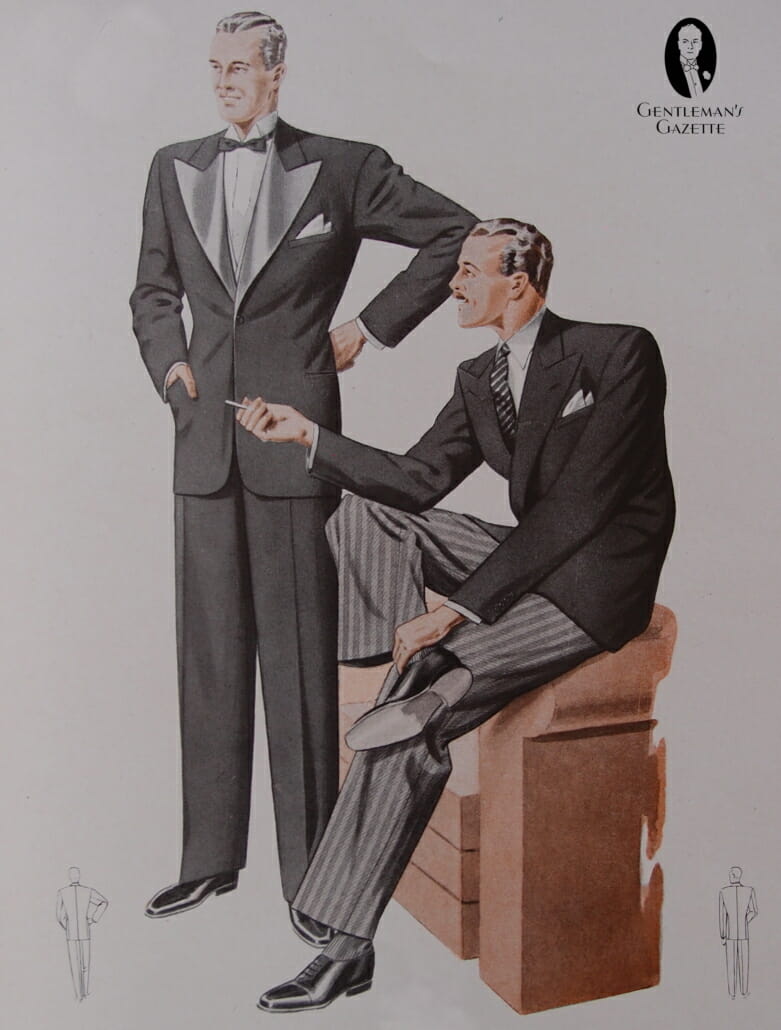

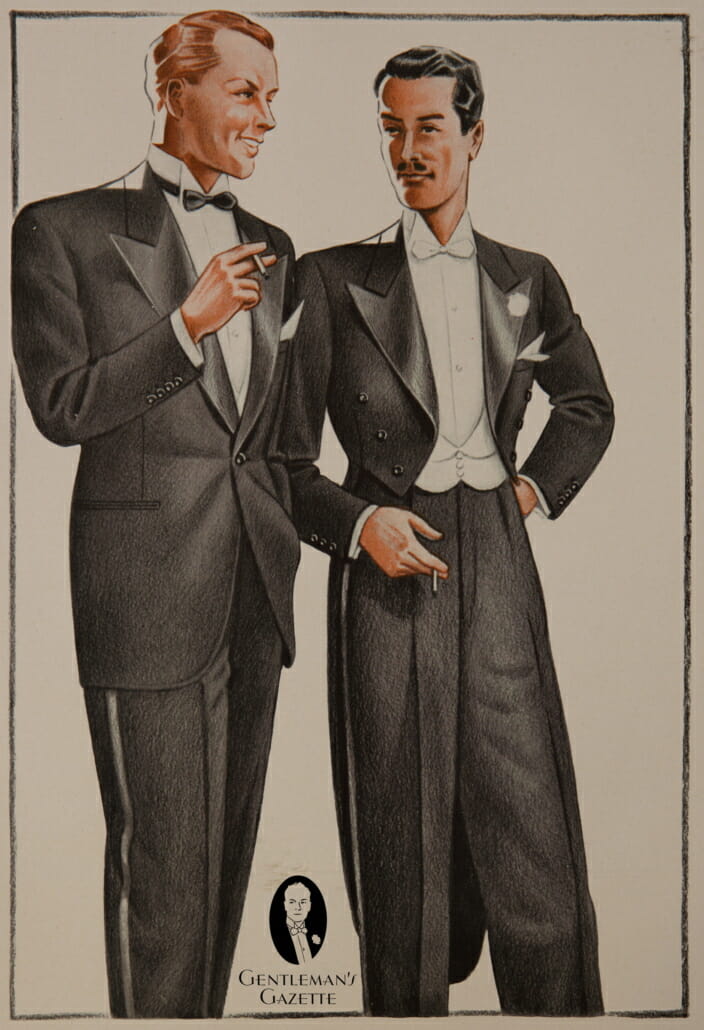

When the dinner jacket first gained popularity in the 1880s it was worn with the full-dress shirt and accessories due to its limited role as an informal replacement for the tailcoat.

Detachable Collars

As the story goes, detachable was invented in 1827 by a housewife in Troy, New York who was tired of trying to remove the “ring-around-the-collar” from her husband’s shirts. Having a collar that was separate from the shirt was not only more efficient for laundering but was also more economical as it allowed the soiled collar to be replaced without having to buy an entirely new shirt.

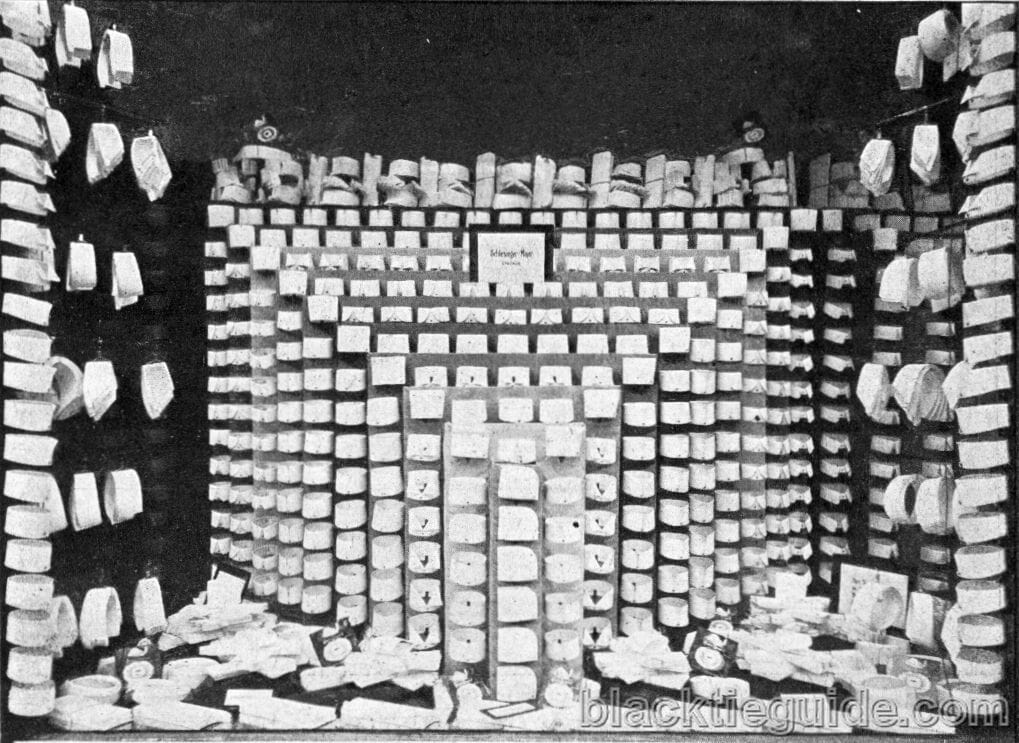

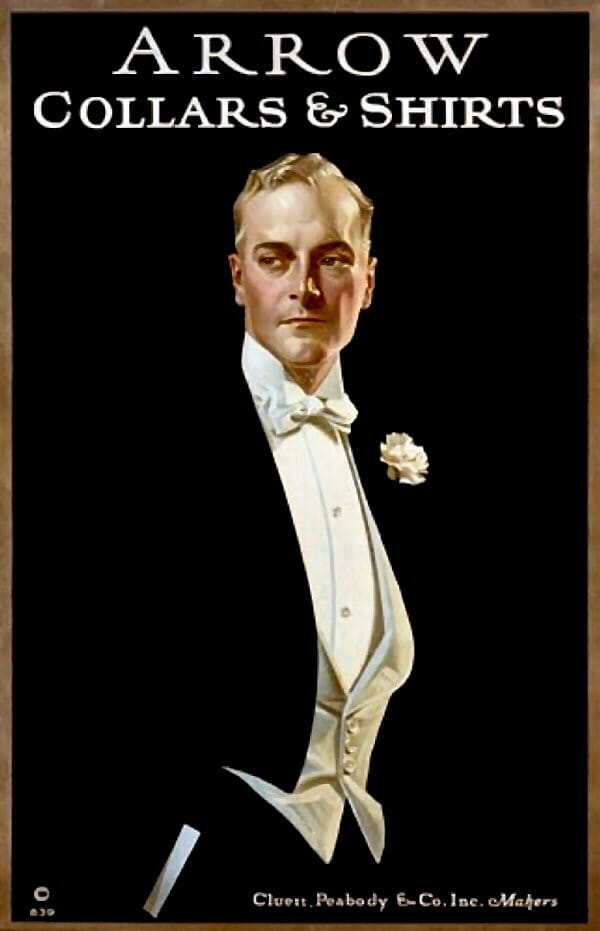

Initially manufactured by hand and constructed of cotton, paper or heavily starched linen, its popularity quickly spread to the rest of the world, particularly among the growing class of office-workers that became known as “white collar” workers. Detachable collars were the height of fashion by 1862 when machines were invented to mass produce them by laminating linen onto thick cardboard stock creating a material known as linene.

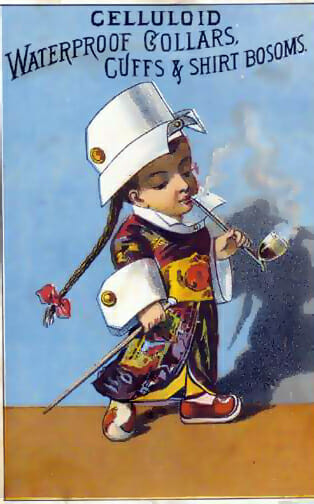

Shortly after its invention in 1870, an early form of plastic called celluloid was interlined with the linen to create an extremely stiff collar that could be cleaned with simple soap and water instead of the elaborate starching and pressing process required for the other materials.

Notably, the very frugality that endeared this invention to the masses was frowned upon by polite society who generally maintained a preference for attached collars on their dress shirts.

Detachable Cuffs and Bosoms

Sleeve cuffs were also available in detachable celluloid styles but were not as popular on formal shirts as were their collar counterparts. While the detachable collar was able to offer a variety of styles and a suitability to different neck lengths, detachable cuffs were simply a way to reduce laundering costs which were not supposed to be a concern for respectable gentlemen.

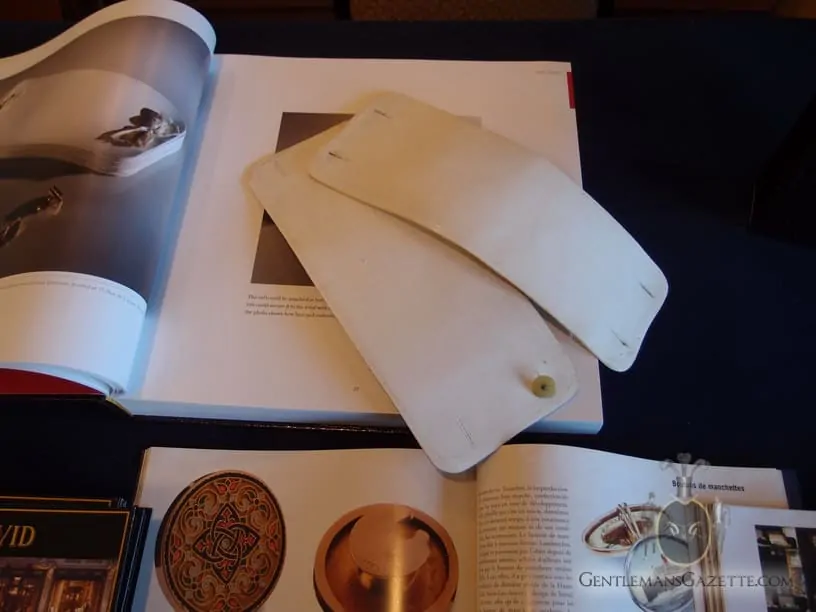

A Dickey (alternately spelled dicky or dickie) is a type of false shirt-front that appeared in the 1820s as a permissible shortcut in the country when fine dressing was impossible. Eventually, they were made of the same celluloid as detachable collars and cuffs for use with evening shirts, buttoning to the shirt’s collar at the top and tucking into the waistcoat or cummerbund below.

Their waterproof, wrinkle-free and stain-resistant properties made them popular with entertainers, musicians and waiters and consequently disdained by well-dressed gentlemen who viewed them as the equivalent of a pre-tied bow tie. Their extreme stiffness and tendency to pop out of place also made them the subject of humor and ridicule.

Stiff or Soft Shirts for the Edwardians

Stiff-Front Shirts

As in the previous era, the Edwardian full-dress shirt featured a stiff bosom of piqué or plain material and the number of studs ranged from one to three throughout the period. New to this era were soft pleated dress shirts with French cuffs which were appropriate only with the dinner jacket, although some mavericks adopted them for full dress.

By the turn of the century the most popular collar styles – whether attached or detachable – were turndown, poke (i.e. upright or “imperial”) and wing. A 1903 “correct dress chart” in The Haberdasher and Clothier dictated the former style for wear with the informal dinner jacket and the latter two models for the tailcoat. As the period progressed the wing collar gradually dominated the other options. Cuffs, conversely, were always to be attached when worn with evening dress.

By 1913 a new trend had emerged which would prove permanent: the material of the full-dress shirt’s bosom, collar, and cuffs were to match that of the accompanying bow tie and waistcoat.

The Rise of Soft-Front Shirts

Beginning at the turn of the century, etiquette guides were allowing plain or pleated front shirts with turndown or wing collars to be worn with the informal new dinner jacket. By World War I these shirts were specifically referred to as soft fronts as in this excerpt from Marion Hartland’s Complete Etiquette:

Gold studs and gold link cuff buttons, or the newer dark enamel should be used, in shirts of plaits or tucks of various widths. These softer styles of shirts are now in high favor and are a sensible and proper innovation. Extremes of styles should be avoided, and many men of conservative tastes still wear the stiff plain linen or piqué bosoms.

Diverse Evening Shirts of the Interwar Period

Stiff-Front Shirts

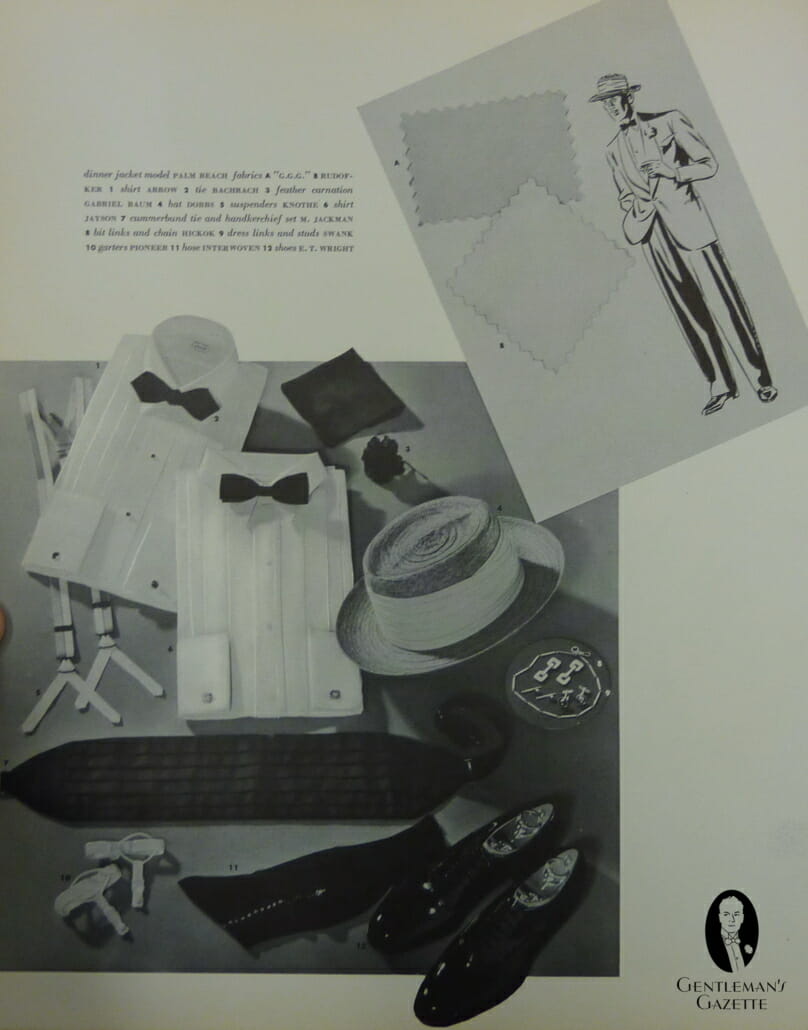

Social formalities were significantly relaxed for practical reasons during the First World War and remained that way after peace returned. Consequently, full-dress was worn much less frequently and there were few developments the corresponding stiff-front shirt. Although the trend of having a shirt bosom, waistcoat and bow tie of matching piqué continued to grow, this was an expensive perk limited to those who could afford custom tailoring. Consequently, plain linen bosoms remained very popular throughout the period.

The detachable wing collar had become the norm by now. The trendsetting Prince of Wales favored a tall version which necessitated a wide opening and very broad tabs that were slightly wider than the bow tie.

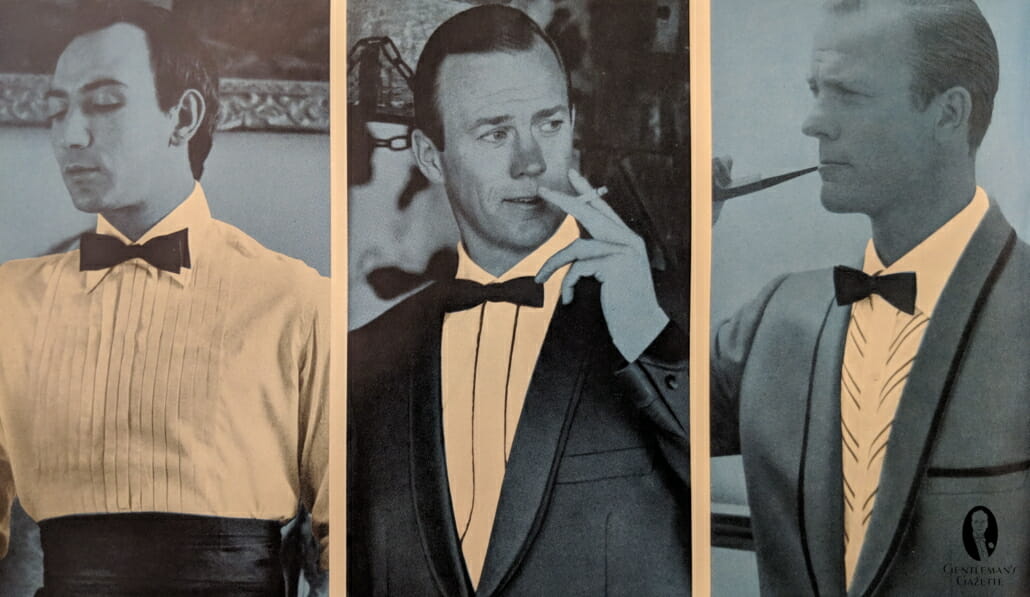

Soft-Front Shirts

By 1928, the Prince of Wales had publicly condemned the boiled shirt of his ancestors and two Men’s Wear surveys from that year revealed that American men seemed to share the sentiment. The periodical reported that while most men continued to favor wing collars and stiff-bosom shirts with their dinner jackets, some of the younger generations had taken to wearing negligee shirts with soft attached collars. The magazine’s editors scolded that “This style mirrors the quintessence of informality, in fact, these men could hardly adopt any more radical style and still be ‘properly’ dressed.”

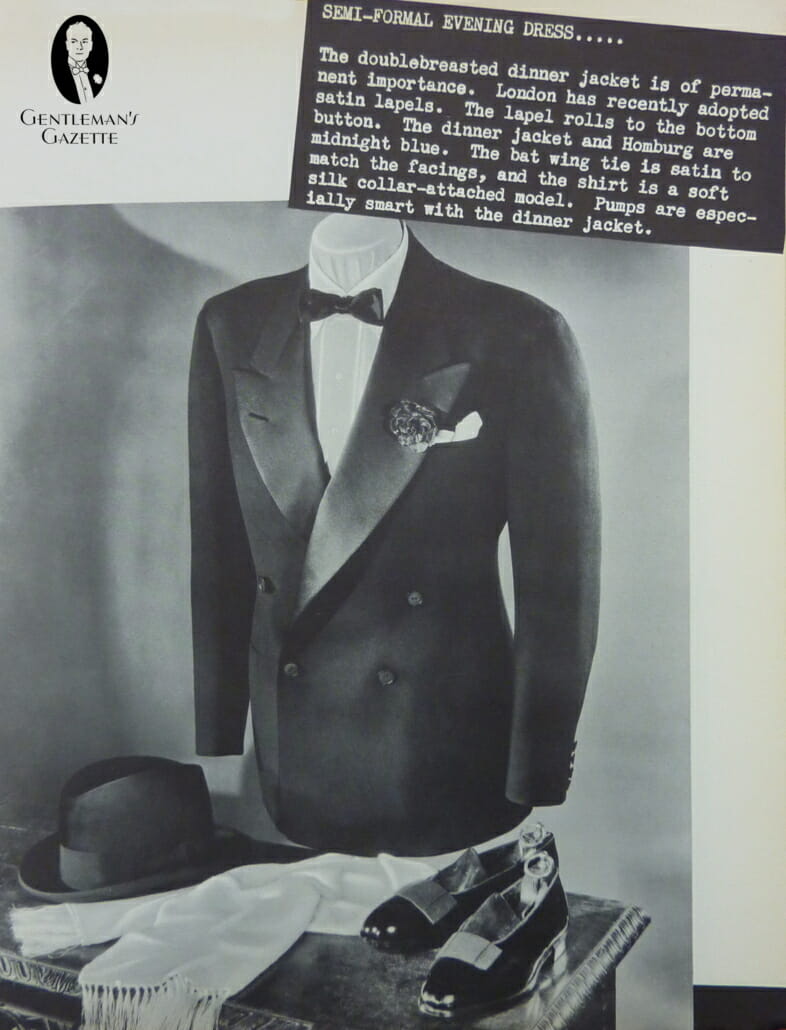

Etiquette authors were equally disapproving and advised their own readers well into the 1930s that the appropriateness of soft or pleated shirts was strictly limited to summer evenings and other equally informal occasions. But they were fighting a losing battle thanks largely to the Prince who regularly wore a soft-front pleated shirt with attached turndown collar and French cuffs whenever he donned his equally informal double-breasted dinner jacket. As a result, Esquire noted in 1937 that the turndown collar had superseded the traditional wing collar by the mid-thirties and was “now virtually standard for informal wear”.

In England, London shirtmakers devised a novel variant that was dressier than informal soft-front shirts yet more comfortable than the formal stiff-front option. The resulting Marcella shirt was an elegant compromise consisting of a semi-stiff bosom fashioned out of formal piqué with a matching turndown collar and cuffs.

Dramatic Mid-Century Evening Shirts

Although social standards were relaxed once more following World War Two there was initially little change in shirts other than the fact that the detachable collar was relegated almost exclusively to white-tie attire which was now rarely seen. As for dinner shirts, the 1948 Vogue’s Book of Etiquette listed some relatively new alternatives: besides the formal stiff-front shirt with wing collar and the less formal semi-starched pleated model with stiff fold collar, the postwar man could also choose a soft-collar shirt either in silk – with plain or pleated bosom – or in broadcloth. According to the book, the latter was “the most informal and probably the most usual.”

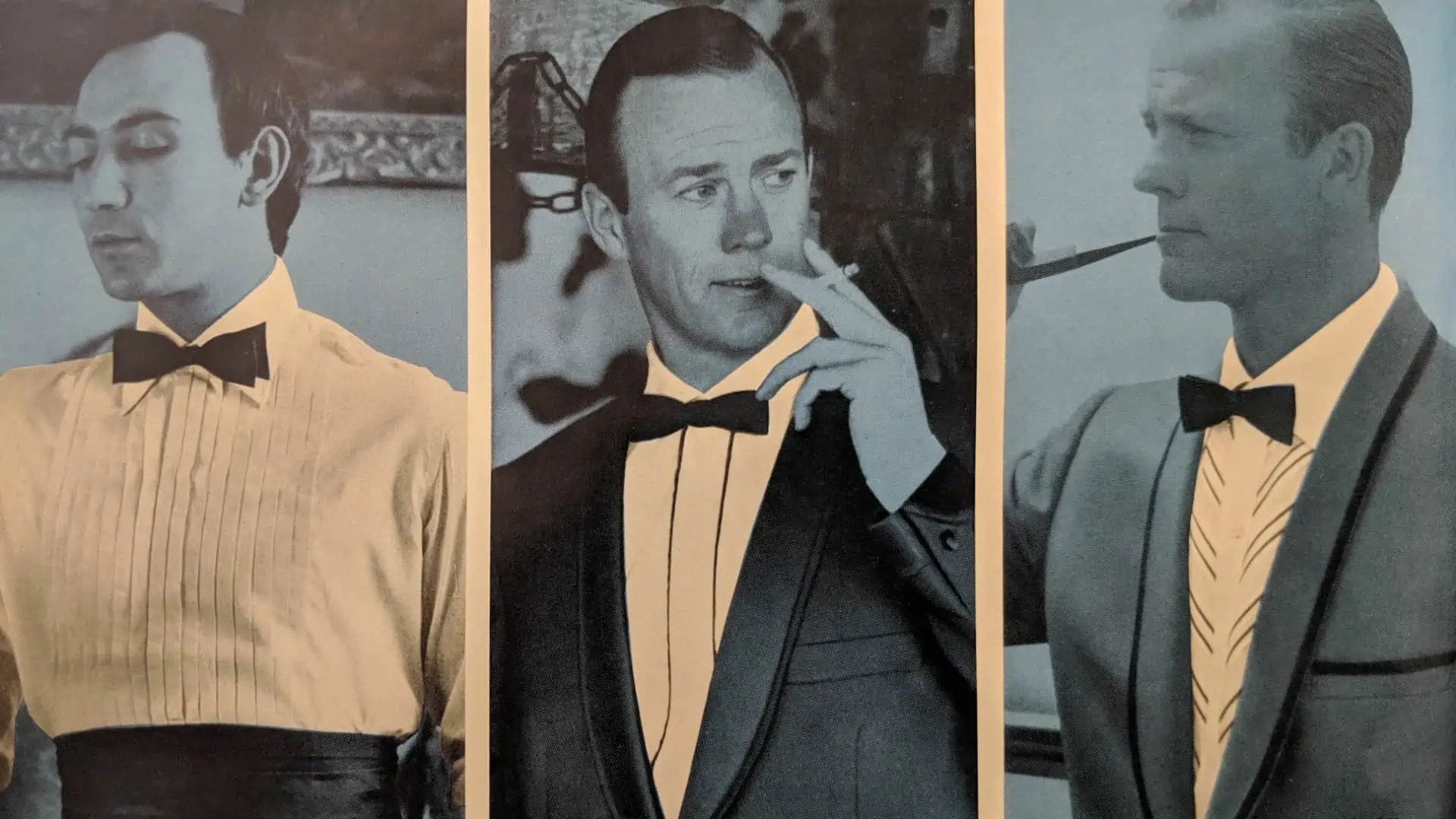

True change in formal shirt styles did not arrive until the late 1950s and early ‘60s when the fashion clock was turned back to the Regency era. Paralleling the Jet Age’s increasingly ornate dinner jackets and evening waistcoats, the stylish formal shirt of the time began displaying columns of understated ruffles or subtly embroidered lace either along the placket or across the entire front of the shirt. After the new style appeared on fashion-forward celebrities at the 1959 Academy Awards the patterns and effects became increasingly elaborate. Other options for shirt bosoms included an ever wider variety of pleats and tucks, frequently with fly fronts that did not require any studs.

The contemporary innovation in white-tie shirts was pragmatic rather than theatric: for the first time, the collar became attached to the shirt. A 1965 ad proudly described Lion of Troy’s version as “the wonderful wing collar shirt that can be worn in complete comfort because the collar is attached and it buttons up the front. Wear it with white tie as usual, or with black tie for a fresh fashion flavor.”

Explore this chapter: 8 Vintage Evening Wear

- 8.1 Vintage Black Tie Etiquette & Dress Codes

- 8.2 Vintage Tailcoats & Tuxedos

- 8.3 Vintage Evening Waistcoats & Cummerbunds

- 8.4 Vintage Evening Shirts

- 8.5 Vintage Evening Neckwear

- 8.6 Vintage Evening Footwear

- 8.7 Vintage Evening Accessories

- 8.8 Vintage Evening Outerwear

- 8.9 Vintage Warm-Weather Evening Wear

- 8.10 Vintage Evening Weddings

- 8.11 Retro Evening Wear