Each bespoke suit has a story, and it starts with the hands of a skilled tailor. But what truly makes a bespoke suit expensive, and what justifies its cost? We sit down with London-based tailor Matthew Gonzalez as he unveils the often overlooked factors that influence the price of a Savile Row suit. Gain a deeper understanding of the value embedded in every stitch and the intricacies that justify the high cost of bespoke suits.

See how Matthew developed his house style

Video Transcript [Lightly Edited for Clarity]:

Jack: We’re here today in London at the Arterton Lounge, and I’m joined by Matthew.

Jack: Hi, Matthew.

Matthew: Good to see you, Jack. How are you?

Jack: Well, thank you. Matthew, tell us a bit about yourself.

Matthew: It’s not a great story, but as you can tell from my accent, I’m originally from Long Beach, California. I studied fashion in Orange County, moved to London when I was 21, and started my tailoring career from there.

Jack: Awesome. So you’re one of the UK’s only American bespoke tailors, am I right?

Matthew: As far as I know, there’s no other bespoke tailor who’s American. And as far as I know, there’s been no other American ever working on Savile Row.

Jack: Very cool.

Matthew: So, that’s my only mini claim to fame, as it were.

Jack: That’s awesome.

Jack: So, where have you worked on Savile Row, if you don’t mind sharing?

Matthew: I’ve only worked in one Savile Row house. But when I moved to London in 2007, my first gig was working with Tom Sweeney. That was at their original shop just north of Oxford Street in 2008. I was there for seven and a half or eight years before I moved on to Alfred Dunhill.

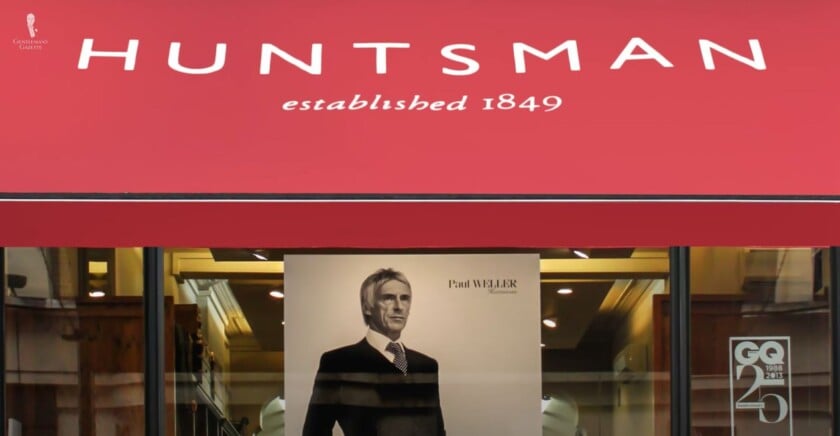

Matthew: I was with Dunhill for a year before I was brought on to Huntsman, where I stayed for just shy of four years.

Jack: Awesome! So, you’ve had a lot of experience with bespoke, especially within the UK.

Matthew: Yes, all of my bespoke experiences are UK-based. Before, when I was in Los Angeles, I started my career as an alteration tailor.

Jack: Oh, I see. Okay.

Matthew: I worked at a department store called Nordstrom. Some of your viewers and readers might know of it. I was just learning how to sew and make alterations, shortening sleeves, taking waists, and such. That’s what really led me to want to elevate my skills and see what the pinnacle of this industry was.

Jack: I see. Because a lot of alterations happen on ready-to-wear garments, am I right?

Matthew: Yes, they do happen on bespoke garments as well, but I’d say most ready-to-wear garments can be altered because you want to really perfect that fit.

Jack: I think that’s one of the things that’s quite interesting. People tend to view ready-to-wear prices against bespoke prices, and there’s this juxtaposition of “Wow, bespoke is expensive.” Is that your view as well?

Matthew: It is expensive. I don’t think there’s any person who could reasonably argue that bespoke isn’t expensive compared to the rest of the fashion market. But the question is, is there value within that expense? When you go to a ready-to-wear shop, you are always going to compromise on something—whether it’s material, the working conditions of the people who’ve made it, the quality, or being priced based on design rather than any other physical element of the garment; you are paying a premium for something.

And margins, as you may know, on most ready-to-wear is very high. When you get into the designer market, they’re even higher.

“But no one becomes a bespoke tailor to get rich.”

I’d love to, but we should have been bankers if we wanted to make a lot of money. Bespoke tailoring is not a high-margin industry, mainly because if we were to price bespoke for what it should be, the number of clients and customers willing to buy from us would be so infinitesimally small.

Jack: Interesting. If you were to give a rough breakdown of the areas where the most money is spent in bespoke, where would you pinpoint the biggest cost in that pie chart?

Matthew: The largest expense per suit is the making cost. We’re sitting in the heart of St. James’s right now, and my bespoke suits are made within a kilometer of this space. My coat maker is still based on Savile Row, and my trouser maker is based in Soho. So, the fact that we have such a localized cottage industry in a major metropolitan city means the cost of producing things will be very high. On top of that, it takes years for a waistcoat maker, a jacket maker, or a trouser maker to train—typically four to five years to become fully qualified—meaning they aren’t making much money during their apprenticeships. So, they need to be reasonably compensated for the rest of their career because they are producing some of the best suits and clothing in the world.

What are the quality hallmarks of a high-end suit?

Jack: Yeah, definitely. Another thing I think a lot of people don’t understand about the bespoke industry is that when they come to a tailor, they’re actually taking home the work of several people. It’s not just one person that does everything from head to toe. Am I right?

Matthew: There are very few—a limited number of tailors who will make everything themselves, but that has largely been consigned to history. You’re absolutely right. If we do a rough count—and we’ll just walk through the process.

Jack: Sure.

Matthew: I am a pattern cutter. I don’t know how many people actually know this, but within our community, there are two distinct roles: the tailor, who sews, and the cutter, who cuts patterns and does fittings. So, strictly speaking, I wouldn’t call myself a tailor when I’m out with my peers. I’d say I’m a cutter. I start out the process. Some larger houses will have a sales associate who deals directly with clients and handles sales, but because I’m a smaller enterprise, I look after my clients. I will help with cloth selection, style details, and lining choices, and then I will take measurements.

Once I’ve taken the measurements, I then go and draft a pattern. A bespoke pattern is essentially a hand-cut pattern made specifically for you based on a system developed over generations. Later on, if we’re upstairs, I can show you my notebook, which is filled with all the pattern drafts I’ve learned from various cutters I’ve worked with. Every single one was taught to them by the previous generation, and every time, we make our own little adjustments to it. While I write them down, this is still an industry largely based on oral tradition, which I think is just so poetic in itself.

Jack: It’s kind of like a recipe in that respect, then.

Matthew: Exactly. I often annotate how I’ve differed from the person who taught me so I can go back to that if needed. And like I said, I can show you those in a little bit. So, that pattern then goes to that cut. When we cut the cloth, we actually don’t call it cutting; we call it striking because we are striking the cloth with our chalk. So again, in the industry, if I talk to other cutters, I might say, “What have you got on this week? Me, I’ve got a bunch of striking on, recutting on, and drafting.”

It’s really about these specific individual elements of the job, which can be done by different people. Some of the larger companies will have strikers whose entire job is to strike the cloth and then move it down the process, creating more efficiency.

Jack: So, the world of bespoke is probably one of the few places where strike action is a very good thing.

Matthew: Yes, exactly. We have striking and then trimming. Again, larger companies will have a trimmer—and a trimmer is essentially someone who takes the cut cloth and then adds all of the necessary canvases, linings, buttons, threads, and shoulder pads to the job specified by the cutter.

If you want a soft shoulder, you need a certain kind of width or thickness of the shoulder pad. If you want a really strong, square shoulder, you need a different shoulder pad. The trimmer will then read all those notes, supply them with the necessary trimmings, and then go on to the coat maker or trouser maker for basting. That’s just a limited view. Once you get into tailoring, it goes even further with pocket makers, finishers, and pressers. The list goes on and on.

Jack: Yeah, absolutely fascinating because on the trimming side of things, as you say, if you wanted a more structured shoulder on a jacket, then you’d need more padding.

Matthew: Yeah.

Jack: So, does that increase the cost of a bespoke suit?

Matthew: It’s really small on, like, the shoulder pad issue, but there are other elements that are more expensive. So, I think, surprisingly, having less lining in the jacket is much more expensive to make. Because then you have to finish all the seams off in ways that they won’t fray but also look aesthetically pleasing. So the tailor has to do more work in order to make that unlined jacket have the same life as a traditional bespoke.

Jack: Because I think it could be really easy to think that a jacket with less lining in it would be less expensive, but the reality is the opposite.

Matthew: Exactly. Yeah. And then when you go into, like, the skeleton jackets, those even get more expensive, even though they have less canvas, less lining. So it’s really weird. It’s an inverse relationship, really.

Jack: Do you make a lot of those yourself?

Matthew: I don’t. I’ll do half-lined jackets, but if someone wanted one, I would happily make one. I’ve made them in the past, but I haven’t pushed that as a particular house style of mine, at least not yet.

Jack: So I see that you’re wearing a seersucker today. Am I right in guessing that this has less lining in it?

Matthew: No, this has… this is a fully lined jacket. It’s a soft shoulder. It’s a softer canvas—the softer shoulder here. There’s no wadding in the sleeve head. So, one of the standard cuts for most Savile Row houses these days is a rope shoulder. I don’t like making a rope shoulder because my inspiration comes from the 1950s and ’60s America when that really didn’t exist. It was more of a flat shoulder line.

Jack: And just to clarify, the roped shoulder is when the sleeve head comes up and round and has a really definite shape, right?

Matthew: Yes. So, like, your jacket has a roped shoulder. You can see because there is that kind of bulge. It looks like there’s a bit of rope in it. Hence, a roped shoulder.

Jack: I see. Okay.

Matthew: If you look at images from the ’60s especially, you won’t see any roping.

Jack: So a much straighter line.

Matthew: Yeah.

Matthew: Now, what I find really interesting, from a historical element, is that that is also true in British tailoring. Savile Row wasn’t really producing rope shoulders in the ’50s or ’60s or even before then. It was really from the late ’60s, ’70s onward that you start seeing it come through, probably most notably with Tommy Nutter. There are some really great archive images where Tommy Nutter’s rope shoulders are really pronounced. And I think that’s really emblematic of the 1970s-style tailoring, at least out of the UK, which just doesn’t represent my story or my interests. Not that it doesn’t look great, which I think it does, but for my house style, I like a much softer silhouette.

Jack: For sure. No, I completely understand that. Tommy Nutter was extremely stylistic in his suits—very suppressed waists, as you say, such a wide rope shoulder.

Matthew: Big lapels. It was kind of looking at taking what was a classic male silhouette and seeing what the outer boundaries were without changing the silhouette drastically. It’s weird because, in suiting, we are confined to a “box.” Menswear doesn’t change drastically, especially in the early to late 19th century. So, Tommy Nutter really pushed the boundaries of how far you can take it with it still being considered a suit. And I think that there are a lot of ramifications to his work because we see people really pushing the boundaries more and more in the ’80s and ’90s in menswear and the fashion realm.

What Men REALLY Wore

Have you ever wondered what men truly wore in the past? In our What Men REALLY Wore series, we’ll take you on a sartorial journey, showcasing the changing silhouettes, fabrics, and trends that defined each decade from the 1900s to the 1960s.

Jack: Interesting. So, does the style of suit you’re cutting influence the price?

Matthew: Not particularly. It’s not the style because, as I said, I don’t really do unlined skeleton jobs. That doesn’t have a direct impact on the overall cost. But you can certainly if you are doing a skeleton bespoke jacket, it would cost more just because the price of making will go up by about 50%. It’s incredibly expensive to make

Jack: So is that the same for details like patch or flap pockets or, like, a pleated back for shooting, for instance?

Matthew: I would imagine that a better entrepreneur would. I tend not to, just because I think you can get a little bit crazy with, “Oh, this costs this much more, and I have to add.” I try to keep it relatively evenly priced. Most tailors base the price of their suits on the cost of cloth. So, that’s actually something that people are surprised to hear. Because our making costs are fixed. We don’t have any economies of scale in terms of makers. If I make one coat with one coat maker, that’s going to cost me the same as if I made a thousand with him.

Jack: I see.

Matthew: Because, you know, I work with my main coat maker. He doesn’t gain any efficiency by having more work. So he can’t make more faster.

Jack: Because he’s not a machine.

Matthew: Exactly. So, we know we have a relatively fixed cost when it comes to the tailors. But when we look at cloth, that’s when we see a variable in price. So if I’m paying X amount per meter, or I’m paying three times that amount per meter, then that’s going to have a direct impact on how much the suit will actually cost at the end of the day.

Jack: So, what’s the most expensive cloth you’ve cut?

Matthew: I did a vicuña suit, and that was very—that was like about fifteen hundred, eighteen hundred pounds a meter. Which is incredibly expensive. The suit ended up costing twenty thousand pounds or something like that.

Jack: Was it just a two-piece?

Matthew: Yeah, it was a two-piece suit. Strictly speaking, we wouldn’t advise anyone to get a vicuña pair of trousers because it’s such a delicate cloth. It will disintegrate. The gentleman who purchased it was a little bit older, had a very large wardrobe, and didn’t have any concerns about the rotation with his suits. So, you know, I’m sure he probably wore that once a year at most.

Jack: So it was a real indulgence. And just something unusual to have.

Matthew: Yeah.

Jack: So what cloth would you recommend, a new person coming into bespoke? It’s their first commission. What would you recommend that they look for in a cloth?

Matthew: Well, it’s a difficult question because it really depends on their lifestyle. If it’s a person who wants to wear a suit every day, then that’s one pathway of thinking. If someone just wants to wear it for occasions and events and weddings, well, then you’re thinking of an entirely different type of clothing. So, what I would say, instead of giving you a “cloth answer” is to look at your lifestyle. Look at how hard you are on your clothing, look at how well you treat your clothing, and then make a decision that’s going to kind of answer all of those different points. I’m very hard on my clothes. I wear them down very easily. So, I look at clothes that are going to be really robust. That tends to mean that I wear heavier-weight cloths because those last longer.

I mean, this seersucker, in particular, is a bit of an outlier. But also, this is not a cotton seersucker. This is 90% wool and 10% silk from Loro Piana. The silk gives the yarn a little bit more toughness in terms of longevity. So, this has actually lasted really well. But, normally, I wear much heavier suits because, one, they tend to look much nicer, and they just work for my lifestyle.

Jack: Understood. Yeah. I get why a heavier cloth would be more of a workhorse in terms of, I suppose, longevity and potentially versatility if you choose a fairly normal color for want of a better term. But yeah, that’s quite interesting. Because I know that you wear a gun club check jacket quite often, it’s quite a beautiful one.

Matthew: Oh, thank you. That’s not particularly heavy. It’s probably 13 ounces. To some, that would be very heavy. I don’t think it’s very heavy, but I think if you asked Italian tailors, especially, they’d think that’s overcoat weather. So again, it depends on where you’re based. It depends on what your lifestyle is. I was actually telling this to a client the other day. She’s commissioning some work from me, and she’s new to bespoke tailoring. She said, “I want something that’s really hard-wearing.” And I said, “That’s no problem. These are like bulletproof.” And she gave me a look, and I didn’t realize that this is a term we use in the industry when it’s a very heavy cloth. It’s obviously not bulletproof, but that’s how we describe it—”Oh, that’s like a bulletproof cloth; that’s going to last you 30 years.”

Want to learn the fundamentals of bespoke tailoring?

Jack: I’ll be honest. I hear that quite a bit when talking to tailors and people in the industry. And because I’m a big fan of the James Bond films and the Kingsman series, I do secretly think to myself, that’s cool.

Matthew: Yeah. No, one of the—She said to me, “Well, one of these days, you actually need to get a bulletproof cloth made.” And then you’re really living up to its description.

Jack: So when it comes to the making time of a two-piece suit…

Matthew: Mm-hmm.

Jack: What sort of rough hours go into each element of the jacket and the trousers, so to speak?

Matthew: So, in terms of getting a base made, it takes a tailor roughly half a day to three-quarters of a full working day to get that made up. Once they’re given it, they can make it in about, you know, just less than a day. Then, actually taking that from going to a finish takes a few days because there’s so much work involved.

Jack: And just to clarify, that’s days in terms of back-to-back hours?

Matthew: No, not like 24 hours—so a full working day, like an 8 to 10-hour working day.

Jack: Got it.

Matthew: It would probably take two or three days to finish a jacket. Most tailors describe their work capacity in jobs per week. So they’ll say, “I can do—I can guarantee three jobs per week.” That’s someone who’s fairly fast if they can do three finished coats a week. Usually, for younger, newer tailors, it’s about one. For fairly established tailors, it’s about two. So, if we use that as a basis, it takes approximately two and a half full working days to finish one coat.

Jack: But the process, from a customer’s point of view, takes longer.

Matthew: Yeah, and that’s because of the capacity issue.

Jack: I see.

Matthew: If I only had one client, and my coat maker only had me as the one client giving him one job, then we could have a finished suit in two weeks. But that’s also based on the availability of the client coming in for fittings. Because we can’t guarantee that we’ll only have one job at any given time, we have to give ourselves appropriate lead times.

Once we have five or six clients coming in—or seven or eight—and I have to make a pattern for each of them, well if it takes me half a day to make a pattern, to make client one to eight’s patterns, that’s four days. So, already, I’ve lost four days of that lead time. Once I give those bases to my coat maker, if it takes them nearly a day, well, that means we already have another eight full working days until that’s done. But that doesn’t take into account work that is already ongoing. They might have finished jackets to make. So if they have two or three finished jackets to make at a rate of two and a half days per jacket, well, now we see why we can’t guarantee next-day service.

We have to reasonably work for everyone in the same capacity. There are always exceptions. If someone needs a suit and they’re desperate for it, we can try to shave off a week or two, but generally, I want to be able to consistently tell all of my clients, “You come in today, and in four weeks that fitting is ready.”

Jack: So another cost of bespoke that I think a lot of people kind of forget about is the fact that they’ve got to come to you for a fitting, a consultation, or whatever part of the process it is. There’s a lot in the 21st century about online bespoke, but I think to get the best outcome, in my personal experience, you’ve got to see the tailor in person.

How to Buy Suits Online

Matthew: Absolutely. Yeah, I mean—

Jack: So, if you don’t mind me asking, how far and wide do your customers travel for you?

Matthew: So, I have a small contingent in the U.S. Mostly, my client base is here in the UK. I have a few who travel throughout Europe and have a few residences. So there’s Swiss space, Denmark—things like that. They often let me know when they’re in town, and then we can arrange a fitting. But that also often increases the lead times because I might say, “Yes, your fitting will be ready in three and a half, four weeks,” but if they’re not back in London for three months, that’s going to significantly impact when they actually get their suit. And that’s just something we can’t work around. I will offer to fly to them, but there’s a cost associated with that. So, it really depends on the desire of the client to get it done quickly.

Jack: Because a lot of tailors, and I know that you do as well, do trunk shows where you’ll travel to other places to hold fittings and things like that.

Matthew: Yeah, I just did my first trunk show in Texas, which I was really pleased about, and I’m looking forward to going back. Trunk shows are their own beast because there are significant costs added to flying out. If you think about it from a logistical standpoint, the worst-case scenario for any tailor is to go to a city in the U.S. and only sell one suit. With the number of fittings required, you have to pay for flights, hotels, and all the expenses associated with business travel. That just eats into any profit you would see on that suit, meaning you need to really have a captive market. You want people who are enthusiastic about what you do. Otherwise, you become a charity. And unfortunately, tailors aren’t in it for losing money. We have to be.

Jack: Of course. Yeah, it’s a business.

Matthew: Exactly.

Jack: Like you say, you’re not doing this because you want to just give people suits.

Matthew: Yeah.

Jack: It’s still a trade.

Matthew: And I think that it’s hard to square that idea when you have such a high price point, but as we said, making suits in central London is incredibly expensive.

Jack: What are the things that make it expensive?

Matthew: Well, one, you have the general cost of living. Just for someone to make enough money to survive, they need to price their work fairly high. Two, it’s the amount of training that goes into making a suit. Three, it’s the level of skill and quality they produce. Not all coat makers and tailoring houses are priced at the same point, and that’s for various reasons. One reason for the tailoring side is that if you’re a new tailor, you’re not going to charge as much as someone who’s been working for 25 years. So there are a variety of reasons why it’s so expensive, also, because of the limited capacity of each individual person. So, as we know in basic supply economics—there’s a huge demand compared to the relative supply of coat makers, meaning they can set a slightly higher price because the tailoring houses will pay it.

Jack: That makes sense.

Matthew: So, there are really a lot of different factors that go into why bespoke suiting is so expensive. Ultimately, if you look at the cost of a suit made in a factory overseas, in the hundreds of thousands, that factory is probably producing the entire suit for less than I pay for the cloth for one of my bespoke clients.

Jack: Oh, wow.

Matthew: For one of my bespoke lines, it’s that element of, you know, if you think about how much a suit from Marks & Spencer costs…

Jack: Oh, so, 2024—probably around what, 150 pounds to…

Matthew: Yeah, maybe 250. That is easily less than what I pay for cloth for a two-piece suit.

Jack: Wow. Okay.

Matthew: So, when you look at it from that point of view, if just the cloth costs more than the entire suit—maybe two or three suits—from Marks & Spencer, then you’re going to see that the craftsmanship, the handmaking, the hand pressing, all of that just builds up to be a fairly expensive, artisan-made product.

Jack: And would you say that in that comparison between the Marks & Spencer suit and a bespoke suit from yourself or anyone else, there’s the benefit of longevity, the fact that you’ve established a relationship with the tailor, and, I mean, do you get people bringing suits back to have work done on them?

Matthew: Yeah, occasionally, you know, some of my clients will have lost weight; they’ll need something altered. That’s fine. We obviously will mend suits, which is—that’s no problem. I like to think of bespoke suiting as multi-generational. We’ve built them in a way that they can survive to be handed down—they’ll survive the next generation.

That might not necessarily be what the next generation wants. They might not want to wear that style of suit, but that’s how we try to make them. It’s also, as I said at the beginning, if you have an interest in how the garment is made—the working conditions, the livelihoods—this has happened, not often, but some of my clients have had a beer with their coat maker. They’ve got to meet the person who put together their suit.

Jack: That’s pretty cool.

Matthew: That’s just an added element of the whole experience, that you can have that connection. And we do other things. One of my favorite examples of turning a bespoke suit into a family heirloom was when I had the idea of getting my client to give me some birthday cards that his children had written for him. We copied the signatures. We didn’t want it to be overt, so we put it inside the jacket, just under the lining. So, under the lining, he—and probably his children—are the only ones who have seen it in person: his children’s signatures.

Jack: How wonderful.

Matthew: That takes it from being a bespoke suit that was made 10 years ago to being a time capsule of, “This is what my child’s signature looked like when they were 10 years old or seven years old.” It makes it so much more special. And to the son or daughter who actually has their name in that jacket, I think that creates the desirability of saying, “I want that because not only did my father wear that, he wore it with my name in it every single day.”

Jack: How sweet.

Matthew: Isn’t that nice? So, there are ways of really adding so much meaning to what a bespoke suit could be.

Jack: 100%. Yeah, and it’s something that becomes so personal.

Matthew: Exactly.

Jack: Perhaps the child will inherit that suit, and it continues to live through them.

Matthew: Yeah, exactly. And hopefully, whether it’s to wear or even just to keep as an heirloom.

Jack: And then that cost becomes so few—I mean so small because it’s lived for longer.

Matthew: Exactly.

Jack: A ready-to-wear garment might not have been.

Matthew: Totally. So, there are many reasons to buy a bespoke suit, but we couldn’t go into all of them. Ultimately, it’s about buying something that is not only made for you specifically. Even if you said, “Can you remake this cloth?” If you, Jack, said, “I want my bespoke suit in this same exact Loro Piana seersucker,” it wouldn’t be the exact same suit. It would be for you. You would choose some of the style details, and we would make things that are only unique to you. So, you really can’t walk around with someone else’s suit. It’s yours.

Jack: Excellent point. When it comes to a suit, would you go for flapped or jetted pockets?

Matthew: Flapped.

Jack: Two-piece or three-piece?

Matthew: Two-piece for me.

Jack: Single or double-breasted?

Matthew: I like single. I like a three-roll-two. It’s just a little bit more comfortable for me. I like the silhouette. I like that it’s a bit more casual, but you can still dress it up. So, yeah, three-roll-two, single-breasted, all day long.

Jack: If you had one piece of advice for a bespoke customer, what would it be?

Matthew: Don’t go to a place that you think you should go to. This is very true—when I was on Savile Row, we would have people come in and say, “Hey, I’m going here. I want to ask you some questions, and I’m going to go next door.” They’d go all the way down the Row and see who’s best for them. That’s probably the best thing you can do. Ultimately, we all have our own styles, we all have our own tastes, and own preferences.

“I would say, think of choosing a tailor like you naturally choose the friend circles that you have. Things click, you know.”

Matthew Gonzalez

I don’t want to hang out with someone just because they represent something that is appealing. I just want things to be easy, and I want to enjoy the time I’m with my tailor. So, go in there, ask questions, and see if they’re right for you.

Jack: Of course. Matthew, thank you so much.

Matthew: My pleasure. Good to see you.

What aspects of bespoke tailoring intrigue you the most? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below!

it’s great if you can afford to purchase “bespoke suits”. How many readers of “GG” can afford too?

I think buying a “Jo’s A Bank”suit is just as good without the added cost,

and if you take care of it should last a long time plus the money that I save can be spent on other accessories that I may want,

besides how many people will “recognize” that you are wearing a “bespoke suit” ? Not many if not all.

The point is not to “be recognized” for wearing a bespoke suit, it’s to have a suit that fits perfectly and that is very comfortable. If others recognize anything about a bespoke suit, it’s that it looks so good. The fabric is far better, the fit is far better, and the person in it looks more natural wearing it. Nobody cares who made it.

I’d argue that everyone can afford to purchase an item of bespoke clothing, it just depends on what value you attribute it. For example, if it takes saving a little for a longer time but the end result is a bespoke piece, then you have been able to afford it.