Fashion Rebellion: Formality is Fractured

In the early sixties, menswear underwent its most dramatic change since Beau Brummell. A textiles exhibit in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London – the epicenter of the period’s “youthquake” of culture, fashion, and music – explains that for the previous 150 years men’s clothing had been tailor-made in plain, dark styles dictated by the mature elite. Now, suddenly, young people with their newfound affluence were challenging the “staid rules of masculine etiquette” that had prevailed since Victorian times. These young modernists, or Mods, preferred clothing that was mass-produced, brightly colored and slim fitting, giving birth to what became known as the peacock revolution.

Formal Gets Frisky

Because adherence to established customs was anathema to a young generation that defined itself by its opposition to uniformity, the concept of “formal” became an increasingly tough sell during the sixties. In response, tuxedo manufacturers focused less on being formal and more on being fancy and subsequently transitioned from merely tweaking tradition to turning it on its head. Menswear magazines applauded this movement away from what GQ described as “the formal formula of monotonous anonymity”. As the periodical noted in November 1969, “the peacock has replaced the penguin and once-sacrosanct traditional formal wear has been assailed by startling – but more elegant than ever – fabrics, designs, and colors.”

Swinging Sixties: Sartorial Shifts

The Mod Look

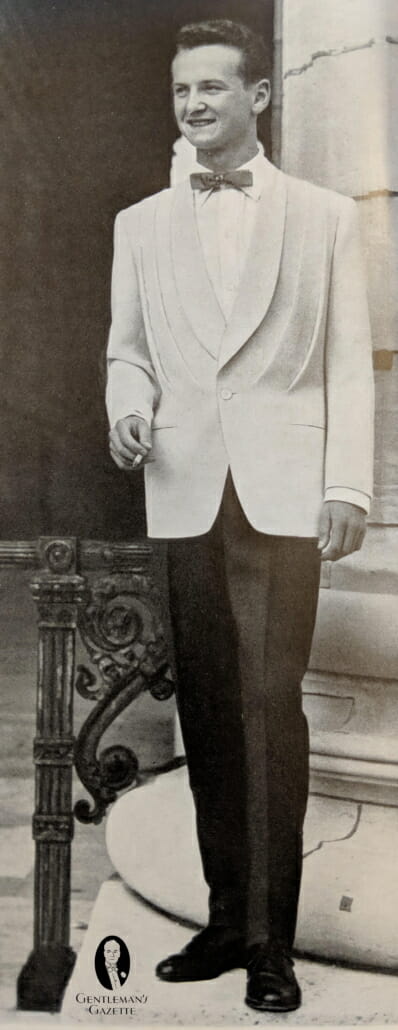

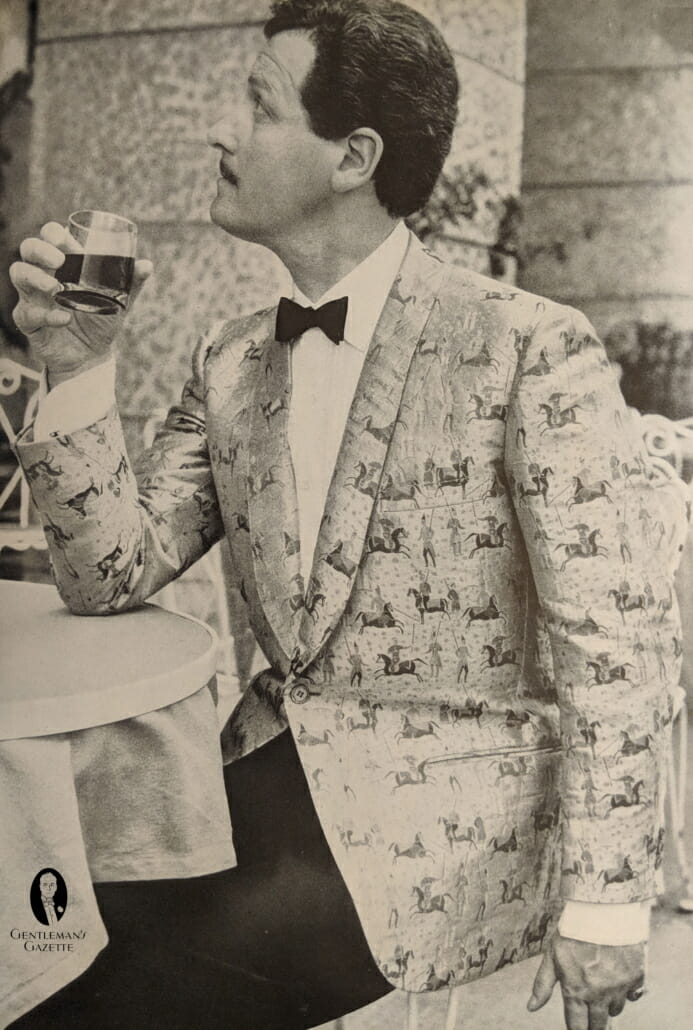

In 1965, tuxedo manufacturer After Six reported that sales of their increasingly popular colored dinner jackets had gone “right through the roof” to the point where they could not keep up with demand. Clearly, the British Invasion had not only landed on America’s shores by this time but was already conquering its formal traditions.

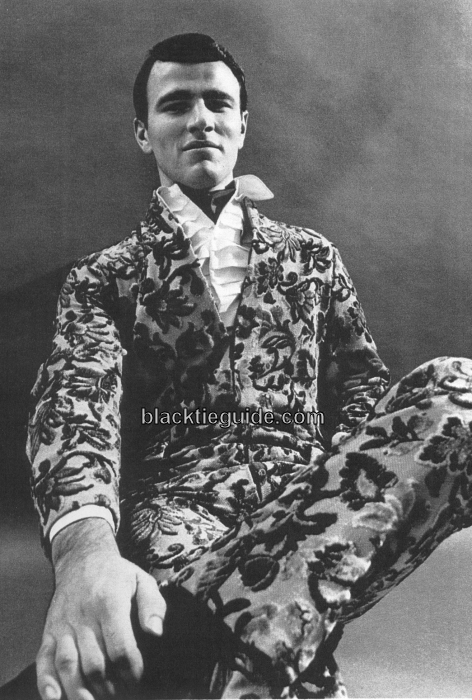

Not long after influencing informal summer jackets, the Swinging London look began to show up in a year-round black tie in the form of the Nehru. This lapel-less, upright-collar coat debuted in American menswear 1966 and soon made the transition to evening wear. After Six featured their version of a formal Nehru in a 1968 ad titled “The no black tie black tie” which depicted a brocaded silk coat worn with a white turtleneck. More than just a catchy marketing slogan, this caption heralded black tie’s surrender of longstanding fundamental principles.

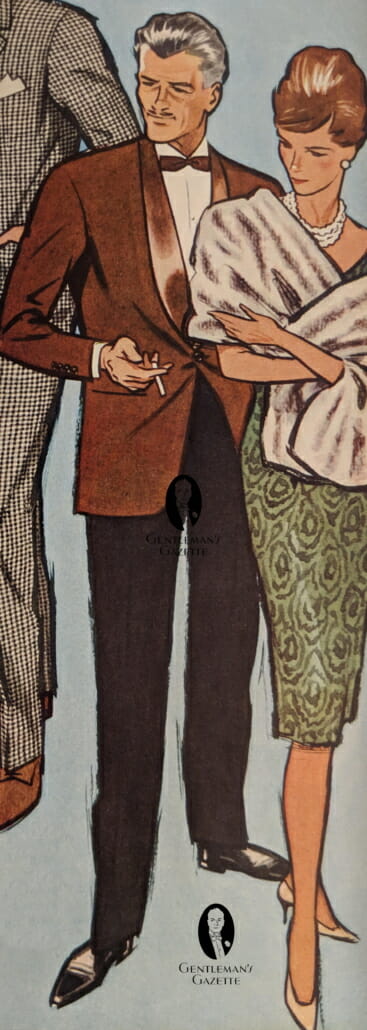

Neo-Edwardian Style

When the Nehru fad began to dissipate (fairly quickly), the Mod look evolved into themore flamboyant Edwardian look. While its name reflected its homage to turn-of-the-century men’s fashions, the trend was equally influenced by the nineteenth-century dandy and his flair for the dramatic.

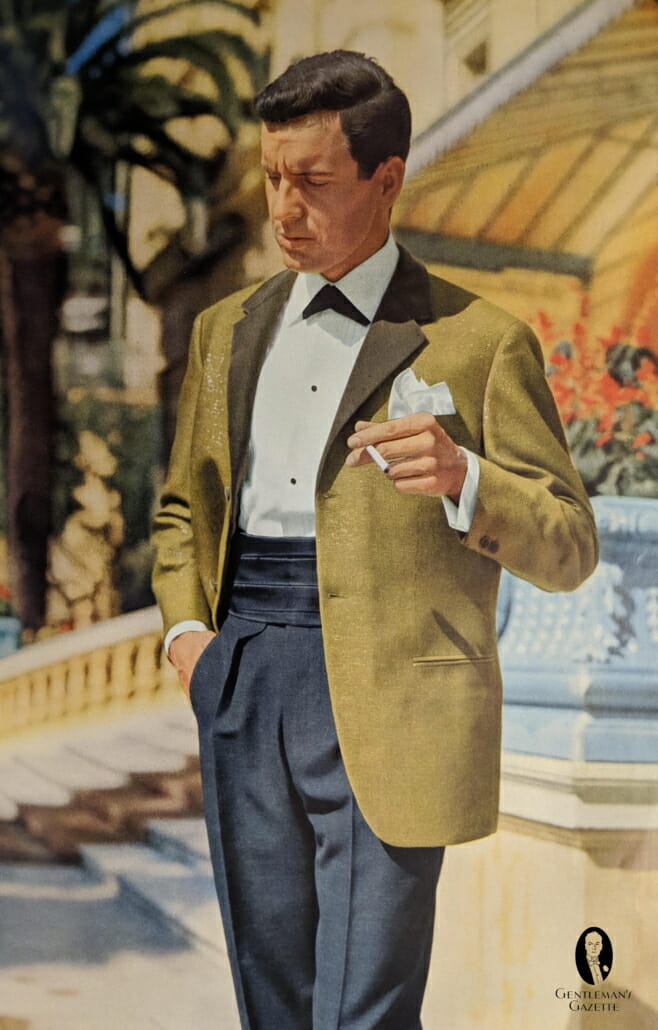

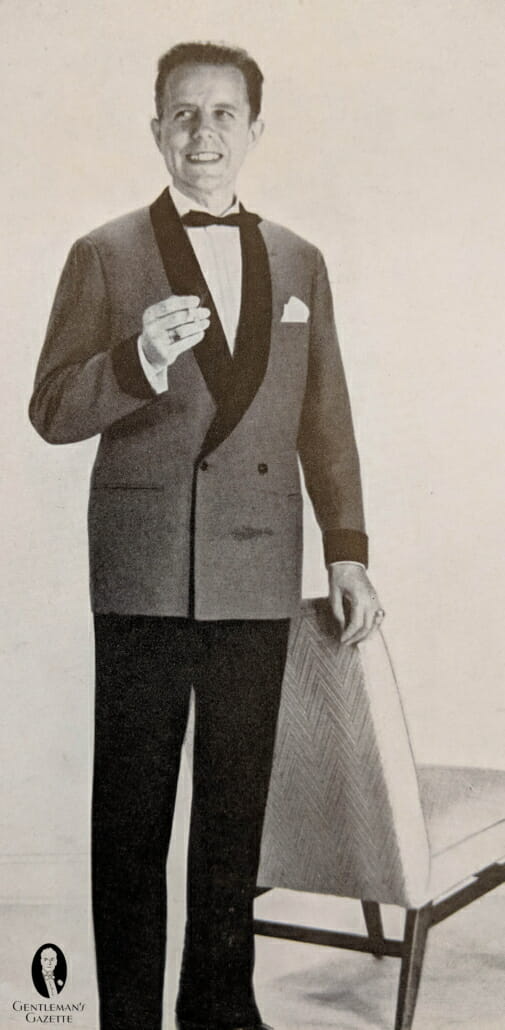

The neo-Edwardian dinner jacket was distinguished by a double-breasted design with wide lapels, square shoulders, suppressed (tailored) waist and a deep center vent. Buttoned with two parallel rows of three buttons, it was sometimes known as a Regency jacket. The cut became longer as the years progressed, elongating into 4-button single-breasted and 8-button double-breasted frock coats. The velvet and brocade materials used for these jackets were fashioned not only in black but also in royal blue, ruby red and emerald green. Contrasting black facings decorated the lapels as well as the flap pockets that had recently emigrated from the less formal summer jackets. Complementing this finery were trousers made from either matching hues or different materials such as white wool, red silk or blue velvet.

Underneath the ornate jackets, formal shirts were becoming equally opulent. The subtle embroidered lace front that had appeared in the late fifties had evolved into columns of small ruffles in the early sixties then blossomed into a forest of oversized frills by the middle of that decade. Synonymous with these developments were the rise of lacy cuffs that spilled over the palm and the decline of the shirt stud which was being increasingly replaced by fly fronts or white buttons. In addition, the understated traditional white fabric began to give way to a kaleidoscope of colored alternatives running the gamut from bright pink to dark blue.

The waistcoat’s previous return to favor in the early sixties was made impractical, not to mention redundant, by the extravagantly ruffled shirts and double-breasted jackets of the later years. When it did appear it was more likely to be a modernized version with a higher cut, much like the vest of a three-piece business suit. The traditional alternative to the waistcoat did not fare much better due to the growing popularity of the wide, satin-covered trouser waistband designed to eliminate the need for what the May 1969 Esquire referred to as “the unsightly scourge called a cummerbund”.

In order to effectively assimilate into such a baroque milieu, the neo-Edwardian bow tie grew to titanic proportions. Although it too was available in a rainbow of colors, black remained the most popular choice and thus the sole link to the classic elegance of years past.

Disco Dress-Up

While the theatrical Edwardian look faded out with the sixties, the enthusiastic disregard for time-honored black-tie principles continued unabated into the 1970s. Formal separates introduced by menswear magazines during the decade included jackets made of brown madras or silver and white paisley, the latter depicted with an open-collared black shirt à la John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever. Not to be outdone, formal trousers appeared in red and black checks, red and blue window pane patterns and a blue and magenta “tapestried paisley” among other designs. As for the formal suit, a November 1970 GQ article appropriately titled “Only the Black Tie Remains the Same” identified floppy bow ties, broad lapels, narrow waists and shorter jackets as uniquely seventies tuxedo traits. Other period manifestations of what the magazine un-ironically labeled “urbane elegance” included evening suits made of brown knit wool, black corduroy and even blue denim, many of which featured trousers cut in the now iconic flared bottom silhouette. Rounding out the stylish disco-era options was the “formal jumpsuit” which the writers claimed not only removed the need for a separate vest but could even stand alone at less formal affairs.

Forgotten Full Dress

Not surprisingly, the aristocratic white tie outfit was virtually unseen in the pages of menswear magazines during this counterculture era and the rare exceptions did not paint a pretty picture. In 1967 a white tailcoat was presented as an example of what London’s bespoke tailors considered to be “fashion sophistication” and a 1972 Lord West ad depicted a white bow tie being worn with a tuxedo as the formalwear company’s “virile interpretation of the classic full dress”. When a traditional full-dress kit finally appeared in the October 1975 GQ it had become so uncommon that the writers incorrectly described it as a “cutaway suit”.

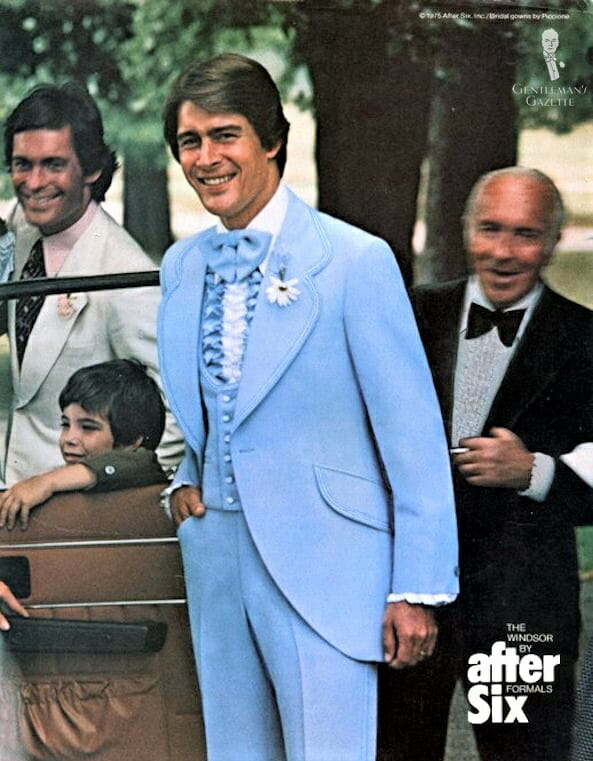

Faux Formal: Rental Costumes

Also absent from the pages of men’s fashion periodicals was the most iconic formal wear of the seventies: the pastel-colored tuxedo. This was partly because the magazines’ editors were shifting their focus from the mass-produced commodities offered by traditional formalwear manufacturers towards more exclusive evening wear produced by newly emerging menswear designers such as Ralph Lauren and Pierre Cardin. And while ads from industry giants such as After Six continued to appear, they generally featured their lines of higher quality conventional dinner suits rather than the prom and wedding rentals that targeted young men with little sense of sophistication or tradition.

Evening Etiquette During the Peacock Revolution

Attire

While the late sixties and early seventies witnessed a revolutionary change in tuxedo stylings, black-tie etiquette remained surprisingly faithful to pre-peacock standards at first. In its 1966 “Fashion Guide for All Occasions” article, Esquire advised readers that despite all the recent innovations in evening wear, “There is very little leeway here. The concepts of formality are narrow indeed and tradition is practically binding.” Other etiquette authorities of this period offered advice that was virtually identical. Essentially, the black or midnight blue dinner suit was still the first choice in the city whether in winter or summer. And while a white dinner jacket with black trousers was common in warm weather at resorts, in the suburbs, and on shipboard, it remained taboo in the city “unless one has a napkin over his arm or a saxophone up to his lips”. Weddings continued to be held to the highest black-tie standards while at the other end of the spectrum the authors acknowledged that there was increasing latitude for colored and patterned jackets and bow ties at relatively informal affairs.

By the early seventies, black-tie etiquette issued by menswear periodicals was becoming noticeably more liberal. The February 1972 GQ “Fashion Handbook”, for example, offered generally conservative guidelines but concluded with a lengthy caveat typical of the times: “while the rules surrounding formal wear aren’t being broken, they are being subjected to a considerable amount of bending.”Published in 1973, Esquire’s Fashions for Today offered almost identical advice for black tie but emphasized that “white tie rules remain relatively rigid”. Consequently, the only full-dress developments of note during this period were an allowance for attached collar shirts, silk pocket squares, and black Homburgs. In addition, piqué was now the universally prescribed fabric for the bow tie.

Occasion

The generation who’s maxim was “don’t trust anyone over 30” had little interest in formal tradition. They rejected proms as archaic and their weddings were apt to be held barefoot in a field. The much protested establishment had also become more casual, forcing traditional authorities such as Amy Vanderbilt to grant significant indulgences. Among other contemporary trends, the author noted that men were now attending the opera in clothes as informal as tweeds and sweaters and that many public dinners had adopted a “dress optional” code which allowed guests to completely dispense with white tie in favor of either the dinner jacket or the even less formal dark suit.

Conversely, a noticeable number of late sixties conduct manuals stuck to their guns regarding the proscription against donning evening wear prior to six o’clock or anytime on Sundays unless employed as a waiter. This emphasis was likely a reaction to tuxedos having become commonplace at weekend afternoon nuptials according to evidence provided by vintage wedding photos taken during broad daylight and a February 1973 GQ pictorial featuring oxymoronic “black tie” daytime weddings.

Relative Formality

It is notable that the 1967 Encyclopedia of Etiquette categorized its tuxedo advice under the heading “Formal Evening, Black Tie”. In the minds of most Americans, black tie’s previous “semi-formal” status was no longer adequate as the white tie tradition receded further into history and the dinner jacket inherited its mantle as the most formal type of attire most men would ever don.

At the same time, the rules for black tie were becoming increasingly gray. Prior to the war, it had been a fairly distinct two-tier dress code with the most traditional attire (black jackets, waistcoats, wing collars) considered appropriate in any season or locale and the least formal attire (white jackets, cummerbunds, turndown collars) generally limited to warm-weather soirees in the tropics or the countryside. Now the tuxedo’s informal variations were increasingly casual and increasingly popular year-round resulting in a sliding scale principle where sartorial appropriateness was judged in the context of each occasion’s unique formality.

Another consequence of the period’s unorthodox variations was that “black tie” and “tuxedo” were no longer synonymous. Instead, the former term became typically associated with the most customary style of dinner suit while the latter would often mean little more than a flashy party outfit.

Re-Thinking the Revolution: Caution for Clothing

In the midst of GQ’s wholehearted endorsement of the reinvention of formal wear, the more conservative Esquire cautioned that blindly dismissing tradition could be just as detrimental as remaining stubbornly conformist. The December 1968 issue explained that the true merit of evening wear’s peacock revolution lay in its alternatives to the traditional black and white color scheme and not, as many mistakenly assumed, in its banishment of the scheme all together. “It’s okay to refuse to wear a Nehru or a turtleneck,” said the writers, “Just wear what pleases you and what becomes you, to hell with conformity.” A few years later in Esquires Fashions for Today the magazine’s editors once again acknowledged the merits of some peacock alternatives while simultaneously cautioning that “a wise man will inevitably choose carefully, bearing in mind that the extreme fashion all too often carries its own built-in obsolescence.”

By the early seventies, it seemed that formalwear designers had taken to heart such sage advice. Showing up alongside the unconventional formal garments during this period were conservative trends – most notably the gradual re-emergence of traditionally dark colors – that hinted at a return to black-tie tradition. This dichotomy of old and new would become even more pronounced with the dawn of an all-new golden age of formal wear.

“Party of the Century”

Ironically, the most famous black-tie party of modern times took place around the lowest point in formalwear’s history. Author Truman Capote’s 1966 Black and White Ball was the most sought-after invitation for American celebrities and New York society – all of whom dressed in traditional black tie.

Iconic Styles: The Good and the Bad

The Powder Blue Tuxedo

The infamous pastel colored suits produced for the youthful prom and wedding rental market were constructed solely for economy and durability. These cheaply-made polyester outfits were about as formal as rented table linens.

The Velvet Suit

In 1972, GQ provided detailed guidelines for this newly popular tuxedo alternative for “relaxed formal situations”. The suit’s color was to be subdued and the (large)bow tie, shoes and socks of a harmonious deep shade. See the Vintage section for more ’70s tuxedo alternatives.

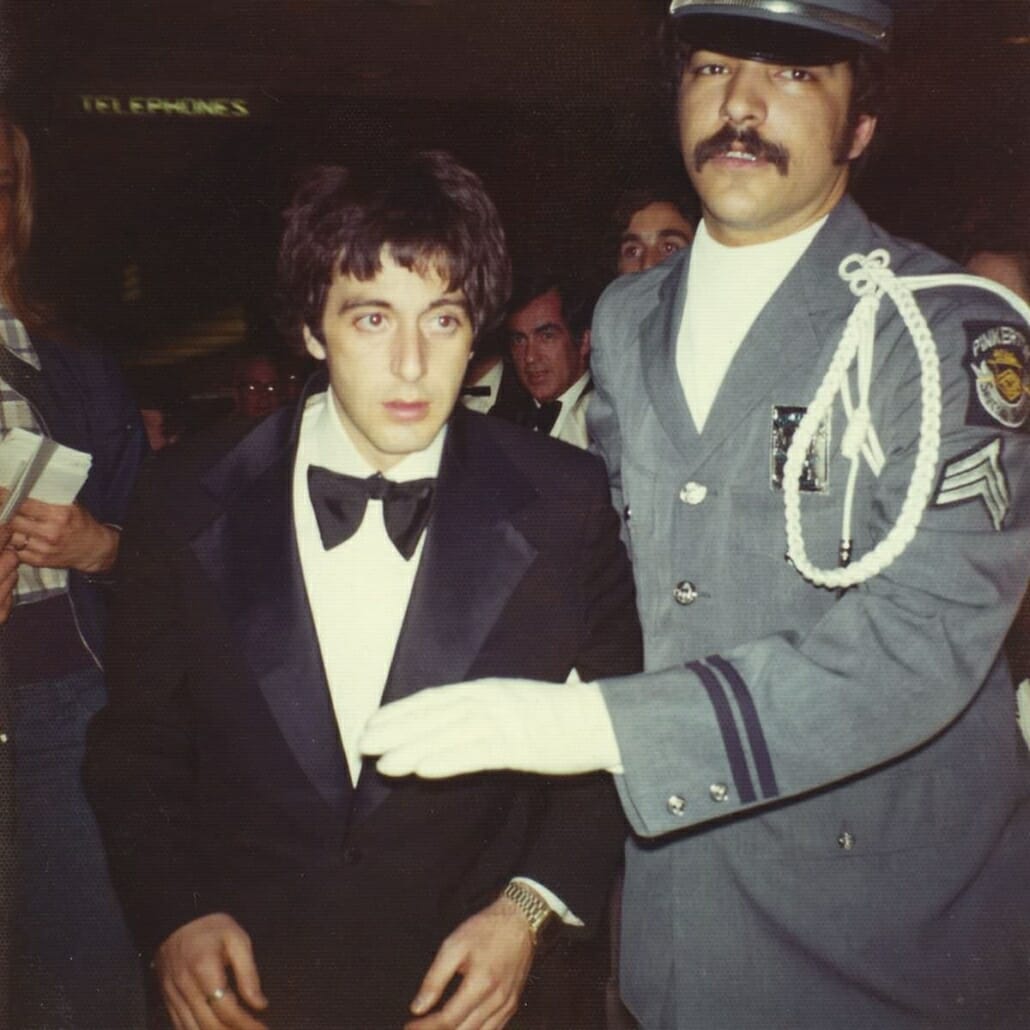

Tuxedo Icons: Dean Martin

Crooner Dean Martin once said “In a tuxedo, I’m a star. In regular clothes, I’m nobody.” He made the suit his personal trademark by wearing it in every episode of his TV variety show that ran from 1964 to 1975.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie