The Meaning of “Full Dress”

Plain and simple as the dress is, it is a sure test of a gentlemanly appearance. The man who dines in evening dress every night of his life looks easy and natural in it, whereas the man who takes to it late in life generally succeeds in looking like a waiter.

Modern Etiquette in Public and Private (1893)

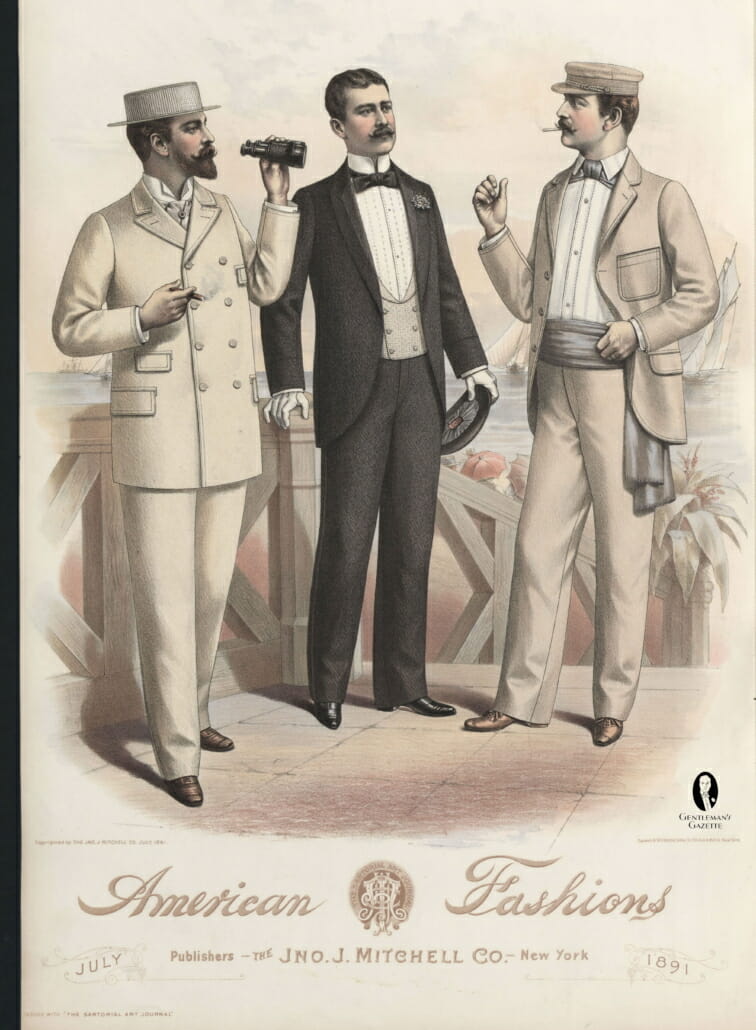

The appearance of full-dress attire in department store catalogs is indicative of just how democratized fashion had become by the late nineteenth century. Class distinction was now entirely in the details which The Man of Fashion: Peacock Males and Perfect Gentlemen says were brought to such a fine art that “a wrinkle across the back of a coat or a crease caused by a sleeve a millimeter too long were social as well as sartorial solecisms.”

- The Meaning of “Full Dress”

- The Full Dress Coat

- The Unique Evening Waistcoat Develops

- The Cummerbund Arrives on the Scene

- Full Dress Trousers

- Evolution of the Modern Stiff Evening Shirt & Collar

- Neckwear: Prominence of the White Bow Tie

- Footwear: Pumps and Button Boots

- The Top Hat is the King of Evening Hats

- Glove Revival

- Other Full Dress Details

- The Meaning of Informal Evening Dress

- The Early Dinner Jacket

- Century’s End: Beau Brummell’s Vision Realized

- Formal Facts

Because of the dominance of English tailoring, the details of Victorian evening dress were largely the same in Britain and America. The following descriptions, therefore, apply to both countries unless otherwise noted.

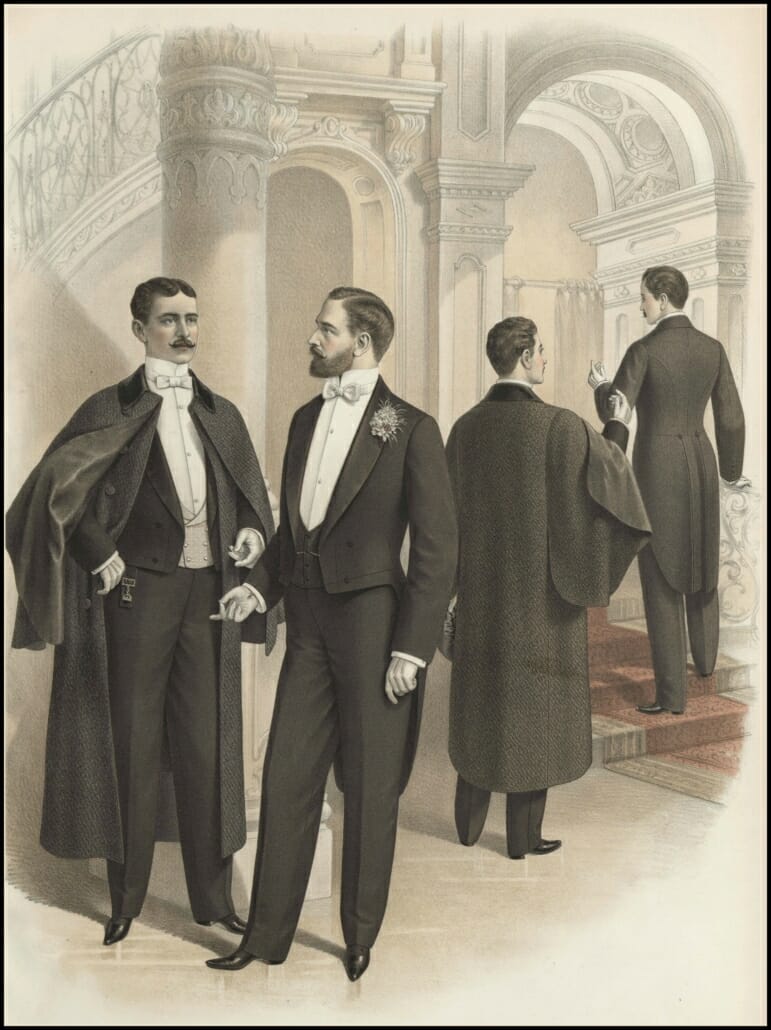

The Full Dress Coat

The roll collar (aka shawl collar) reappeared on the dress coat in the 1880s thanks to its adoption by “mashers” – the middle-class English dandies of the day – and eclipsed the conventional style of lapel by 1886. It was faced to the edges in either black satin or corded silk. When traditional lapels returned to favor in the following decade they were initially faced to the buttonholes as in the past than more likely to be devoid of the multiple buttonholes and trimmed all the way to the edge. One feature that was consistent was that they were cut in the peak style that has been standard ever since.

The roll collar trend may have been responsible for the ultimate demise of velvet collared evening tailcoats around the same time. Stitched cuffs also fell out of fashion in the late Victorian period.

The Unique Evening Waistcoat Develops

By now the low-cut style was unique to evening waistcoats. The deep V front remained popular at first then was superseded in the mid-1880s by U- or shield-shaped models which were more effective at displaying the formal shirt front. Single-breasted types were initially preferred but the double-breasted grew in favor from 1890. Regardless of the model, the waistcoat collars were always shawl style.

In England white piqué gradually ousted black fabric which became consigned to informal dinner wear. Conversely, black waistcoats to match the dress suit were the norm in the United States where white versions were considered a luxurious alternative because of the associated laundering expense.

The Cummerbund Arrives on the Scene

English officers serving in British East India had adopted the local practice of wearing a sash around the waist in place of a waistcoat. In the late nineteenth century, they adapted this “kamarband” into evening wear and exported it back to Europe where it was hardly a resounding success with full dress. One French fashion magazine described it in 1873 as a “wide belt that constitutes yet another grotesque fashion whose slovenly appearance hardly requires mention.”

Handbook of English Costume in the Nineteenth Century notes that some maverick dressers traded in their waistcoat in favor of black or crimson silk waistbands. But by 1895 English etiquette authorities were noting that “the cummerbund is hopelessly vulgarized” and it quickly fell out of fashion, at least in civilian attire.

Full Dress Trousers

By this time full-dress trousers were typically made of the same material as the dress coat and usually featured side braid. They remained a closer-fitting cut than day trousers.

Evolution of the Modern Stiff Evening Shirt & Collar

The late Victorian period ushered in the stiff evening shirt that is still the standard for full dress today. It became known colloquially as a “boiled shirt” because boiling was the most effective washing process to keep linens white and to remove the copious amount of starch from the undergarment’s four-layer bosom. These bosoms were made of white piqué or linen, the latter either plain or pleated, and generally took one or two studs.

Invented in the United States in the 1820s, detachable collars and cuffs had become internationally popular by the late Victorian era because they could be reversed when soiled in order to save on laundry costs. However, this frugality was frowned upon by polite society who generally maintained a preference for attached versions. Evening dress collars were straight standing and often featured folded over tips known as wings. Cuffs were either buttoned or held together by decorative metal links.

Neckwear: Prominence of the White Bow Tie

By the 1890s black bow ties were outré for formal evening dress and only white ties of piqué, lawn (a fine sheer linen or cotton fabric of plain weave) or linen were deemed acceptable. They were typically narrow and often made in sized models rather than adjustable ones. Pre-tied versions were also available although period etiquette guides repeatedly stressed that “made-up neckwear of any kind is not worn by well-groomed men.”

Footwear: Pumps and Button Boots

Pumps or black patent leather button boots continued to be regulation footwear for evening dress. The bows featured on pumps were now often made of a corded material called petersham. White silk stockings were still seen in evenings at first but black silk dominated by the end of the century.

The Top Hat is the King of Evening Hats

The black silk top hat remained de rigeur for day and evening dress despite men’s general distaste for it as voiced by Modern Etiquette in Public and Private:

When in town you must always wear a high hat. Every shaft of ridicule has been urged against it in vain. It is costly, it is heavy, it is unpicturesque and stiff-looking : but nevertheless, it has this one merit in its favor – that it makes a man look like a gentleman.

The collapsible version of the top hat continued to be a popular evening option as it could be easily carried under the arm at a ball or folded under the seat at the opera. Its nicknames during this period were, appropriately enough, the crush hat and opera hat.

Glove Revival

Evening dress gloves were still made of white kid although pearl and pale yellow remained popular alternative colors. As for the etiquette of covered hands, in 1884 The Mentor noted that “for several years gloves were little worn by men, especially with full dress, even at dancing-parties and balls, but of late the wearing of gloves, particularly at parties and balls, is the rule rather than the exception.”

Other Full Dress Details

Correct Dress, an 1887 American guide to menswear, epitomized period advice regarding evening jewelry for gentlemen: “No jewelry whatever is used except that which has a direct purpose and this is kept as simple as possible. It is limited to studs and cuff buttons [cufflinks], with a partial exception in favor of the watch chain.” These studs and links were often mother of pearl or enamel with gold, or simply plain gold or silver. Watch chains of precious metals were a bit gauche; Correct Dress preferred ones of black silk instead.

A new development in Victorian evening accessories was a flower worn in the dress coat’s buttonhole, “one of the few allowable devices” to brighten up a man’s evening attire.

To protect his shirt front from soiling while in transit, a gentleman of the time would don a white silk muffler with his overcoat or evening cloak.

Better yet was a dress shirt protector, a pad of white quilted satin faced with white silk that was popular at the end of the century.

Finally, The Complete Bachelor: Manners for Men advised that a plain white linen handkerchief “must be present but not seen.”

The Meaning of Informal Evening Dress

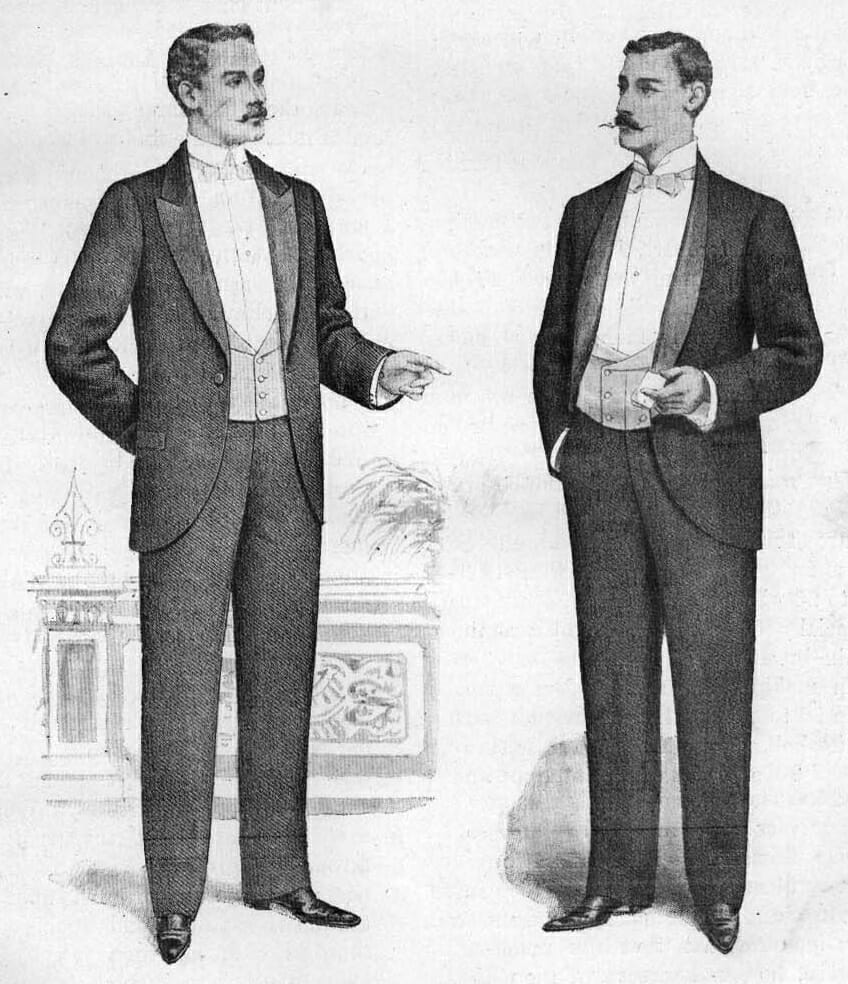

The Early Dinner Jacket

The original dinner jacket was essentially tailored like the short single-breasted jacket of a casual lounge suit (sack suit in America) with a shawl collar imported from the smoking jacket and finishes copied from the full-dress coat. Details of the jacket’s development through the 1890s are provided by The Handbook of English Costume in the Nineteenth Century:

Cut like a lounge but not intended to be buttoned, so that the foreparts were narrow, with roll collar continuous with lapels turning low to two buttons, becoming one button in 1898. The back invariably cut whole and sleeves finished with cuffs (1899). The roll was completely covered with silk, satin, or velvet . . . Materials: as for the dress coat [at first a fine vicuna; from 1895 often replaced by a fine hopsack or twilled worsted] or of velvet.

Peaked lapels (aka “pointed” or “step roll” collars) were imported from double-breasted garments and by 1899 they had become the most popular style.

Accessories

The dinner jacket was worn with the same accoutrements as prescribed for full dress – including a white or black waistcoat – with the exception of a black silk tie that sometimes replaced the white lawn tie.

Century’s End: Beau Brummell’s Vision Realized

By the end of the nineteenth century, Beau Brummell’s vision of one hundred years prior had for all intents and purposes become universally accepted full dress. The only exceptions – the black waistcoat and bow tie – were by now limited to full-dress alternatives. In the upcoming Edwardian era, they would be relegated exclusively to informal evening dress and the dinner jacket so recently introduced by the new king would begin its gradual ascent to evening supremacy.

Formal Facts

Formal Facts: Ready-To-Wear

Americans had greatly improved the fit of ready-to-wear (“ready-made” or “off-the-peg” in the UK) clothing by the mid-1830s and it became increasingly popular with the British middle class in the late Victorian era. However, the English upper class continued to define themselves by the perfection of Savile Row tailoring and would have no doubt been appalled at the thought of purchasing mass-produced evening wear.

Formal Facts: Open Fronts and Backs

Prior to the end of the century, men’s shirts only had a partial opening in front and were slipped on over the head, and were essentially what we would describe as a popover shirt today. Around 1895 the modern “coat-shirt” appeared which buttoned the entire length of the garment. This was especially popular for evening shirts perhaps because it was more fitted and the starched bosom could avoid wrinkling during the dressing process.

Another modification of the time was a back-buttoning style that allowed the bosom to be an undivided whole and the studs to be inserted prior to wearing. This style of formal shirt remained popular into the 1930s.

Formal Facts: The Dickey

Like the detachable collar and cuff, the dickey was another convenience intended to save on laundry costs. However, this faux shirt front was often a source of ridicule and considered “a feature of the lower and middle-class trade”.

See the Vintage Waist Coverings page for details of the cummerbund’s evolution through the twentieth century.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie