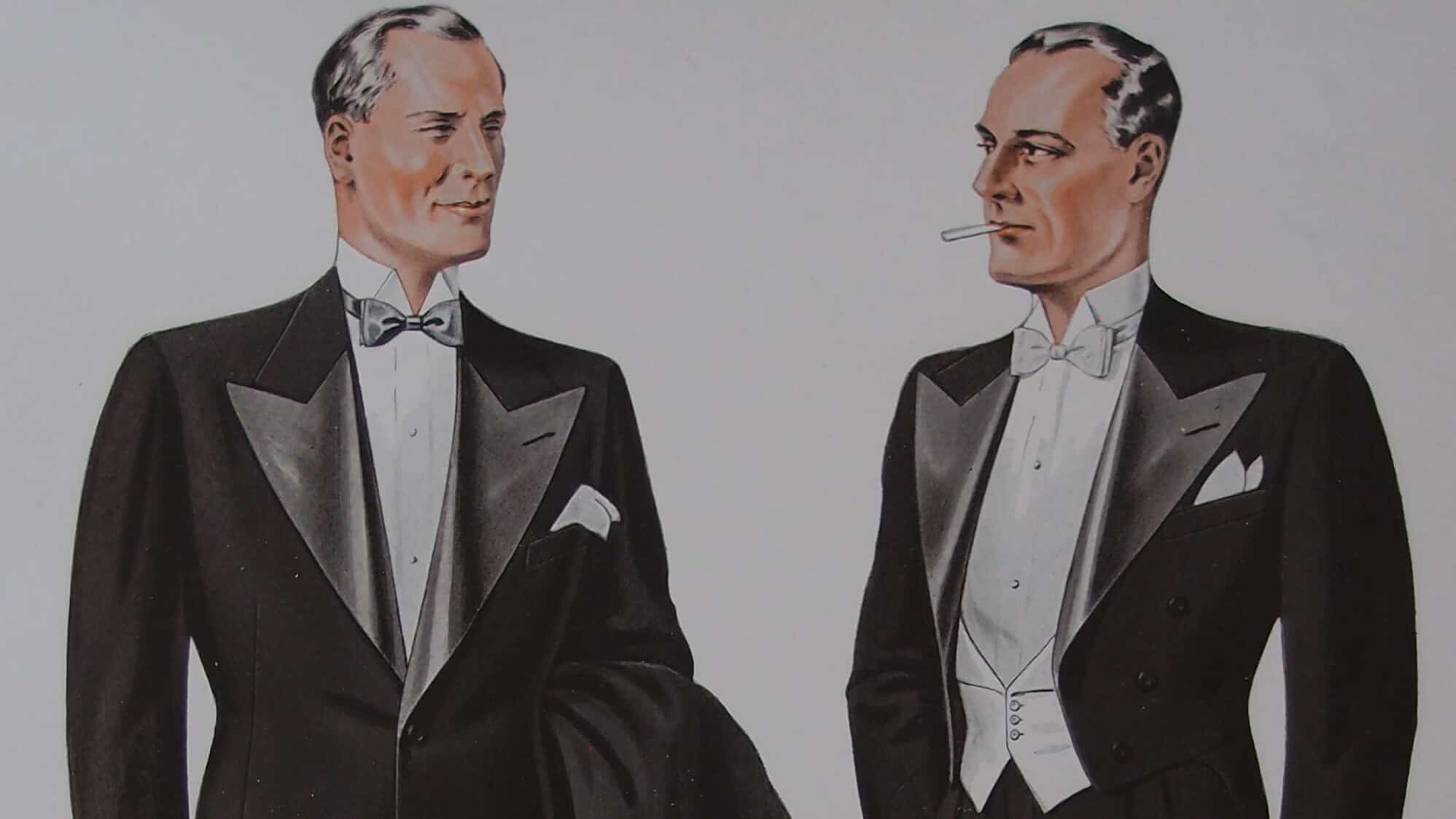

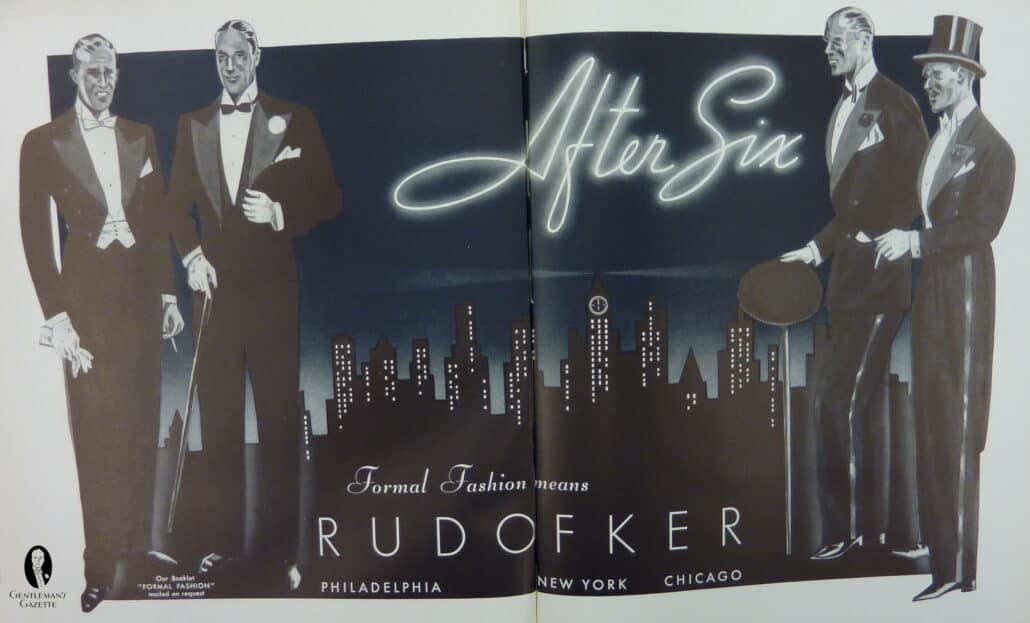

Dressing for the occasion is now a habit with the masses as well as the ‘idle rich’.

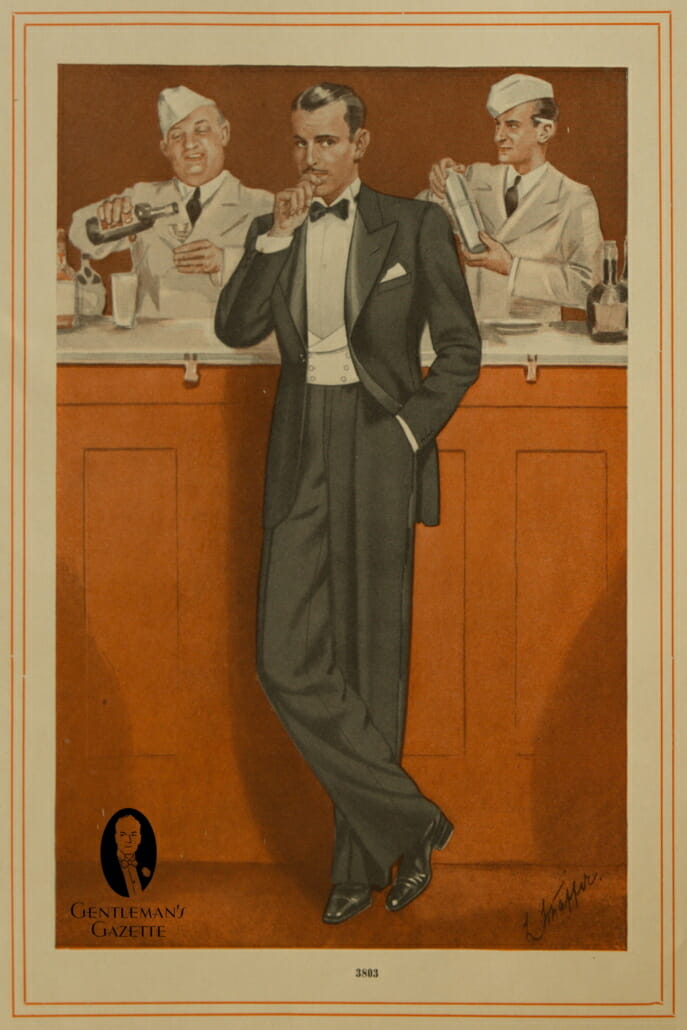

tuxedo ad, 1930

The Expanding Appeal of Black Tie

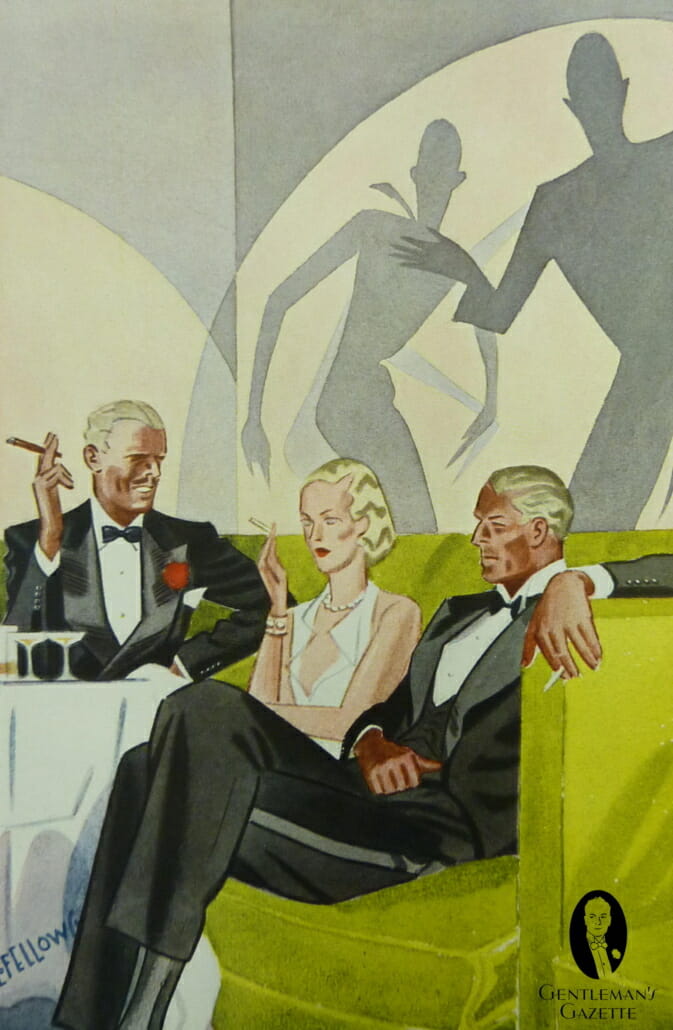

Remarkably, the greatest chapter in the history of evening wear – and arguably menswear in general – is the era marked by the Great Depression. At a time of extreme financial hardship for so many, the wealthy elite maintained an after-six wardrobe that was not only elegant but sometimes downright decadent. In 1935 a New York Herald Tribune society writer calculated that a “well-attired” New York gentleman’s evening kit could be worth as much as $4,975 once his jewelry and fur coat were accounted for, the equivalent of a staggering $90,000 today. It was this glamorous lifestyle that Hollywood capitalized upon when catering to mainstream America’s desire for inexpensive escapism and in the process elevated the tailcoat and tuxedo to iconic status.

- The Expanding Appeal of Black Tie

- Classic Comfort and Style

- “Suave and Sleek” Waistcoats

- The Dress Suit: Fickleness of Fashion

- Full-Dress Linens for Shirts & Waistcoats

- The Rise of Informal Jackets and Shirts

- Other Style Trends

- Warm-Weather Black Tie Heats Up

- Return of the Cummerbund

- Classic Etiquette: Distinguishing Formal, Semi-Formal, and Informal

- Golden Sunset: The End of an Era

- Formal Facts & Style Icons

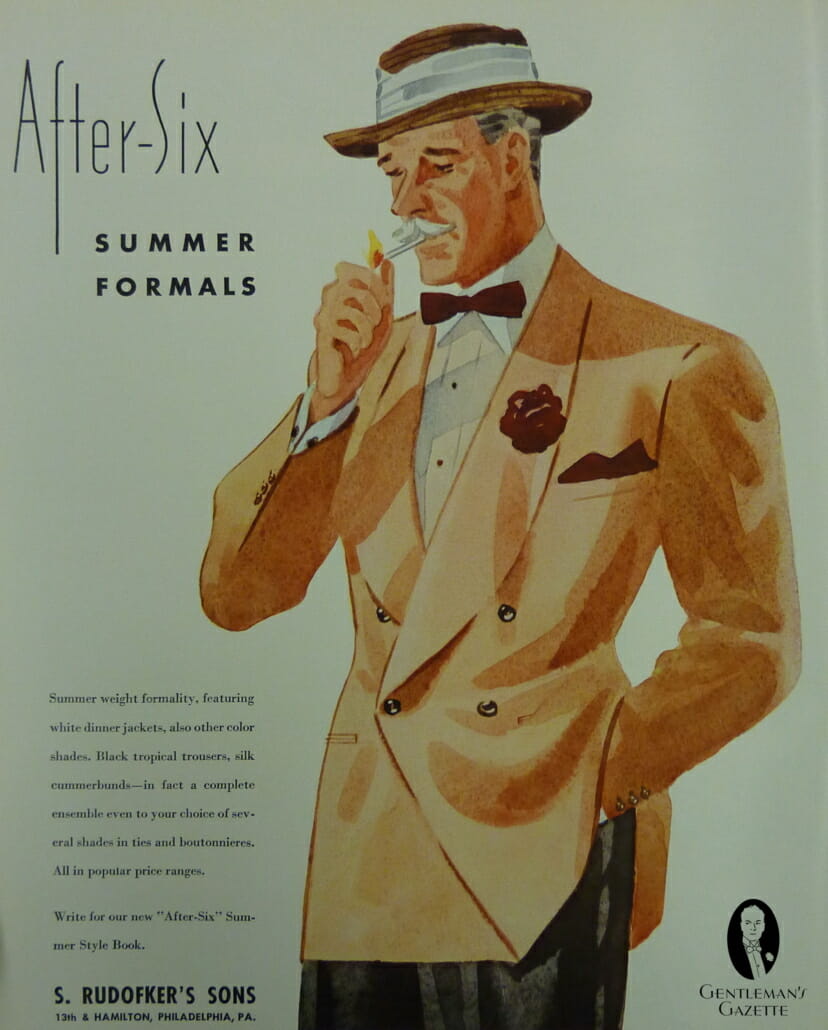

Silver-screen elegance became more affordable to the average man thanks to the increased availability of ready-to-wear tuxedos which were first mass-marketed by Philadelphia tailors S. Rudofker’s Sons, predecessor to industry giant After Six. Even more economical was the newly established option of simply renting one’s formal wear on a daily basis. As a result, Rudofker jubilantly advertised in 1930 that the habit of dressing for the occasion previously confined to the “idle rich” had now expanded to include the masses: “Business Men, Truck Drivers, Collegians, Farmers, Office Workers, High School Youths: They’re All wearing Tuxedos!”

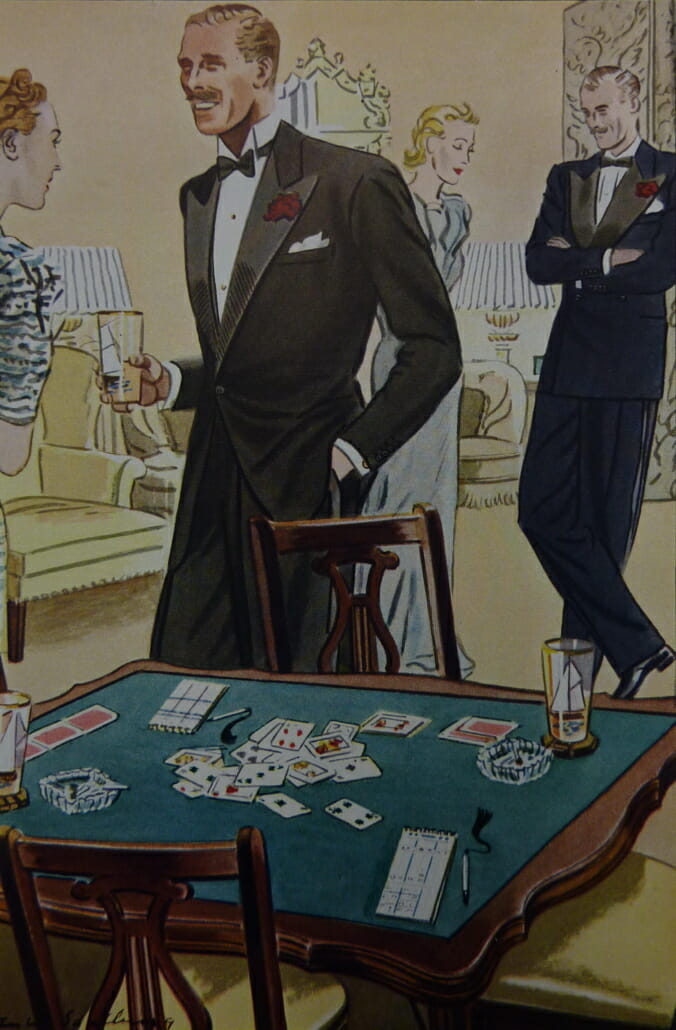

Classic Comfort and Style

Another primary factor in the dinner suit’s surging appeal was surely its improvements in comfort. Menswear historian G. Bruce Boyer explains that before the thirties a gentleman’s evening dress kit consisted of a dress suit or dinner suit of 18- to 20-ounce wool, a board-stiff shirt of heavy cotton with a tall starched collar and extensive accessories and jewelry. “It boggles the mind, nay the whole body, to understand how any but the stateliest dances could ever have been negotiated.” Then during the interwar years shirts became softer, waistcoats became cooler and, most notably, evening suits became lighter than regular suits. As the After Six corporate history once summed it up, “tuxedos were finally being made for dancing.”

Lastly, there was the impact of style. For nearly a century male apparel had been focused on appearing respectably inconspicuous but the youthful influence born of the jazz age – epitomized by the eminently stylish Prince of Wales – liberated menswear from such constraints in the 1930s. For the first time since the Regency fashion was fashionable. So it was that 1920s eveningwear trends which had been originally confined to elite social circles began to spread to the masses.

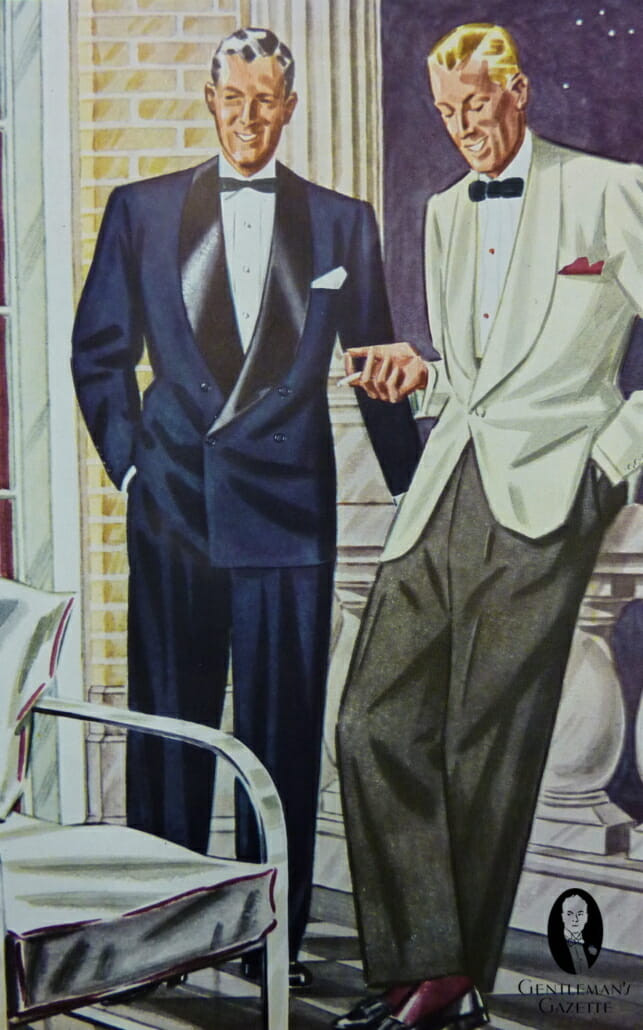

Midnight Blue

The Prince’s debonair color preference for after-six attire was imported to America by Hollywood movie stars and was all the rage by the mid-thirties. Frequently described by enamored journalists and advertisers as being “blacker than black”, it was at first limited to the least formal variations of evening wear but its popularity quickly expanded until by 1934 menswear periodicals were promoting it for all types of evening dress. In 1935 it was reported that mills making fabrics for formal dress expected sales of midnight blue to equal or even exceed those of black that season. Their predictions proved true and by the late thirties, etiquette and sartorial pundits were announcing that this previously alternative color was now the primary choice for dress suits and dinner jackets alike.

“Suave and Sleek” Waistcoats

“Waistcoats have become a high style item,” observed Apparel Arts in 1933. “No more of the thick ill-fitting affairs but today a suave and sleek arrangement.” Gentlemen continued to personalize their evening suits through their choice of single-breasted or double-breasted models, usually with a narrow V-shaped front opening. They also had the option of the traditional full-back style or the newer and more comfortable backless design introduced in the previous decade by England’s regal maverick. By the time the Prince became king in 1936 Esquire was reporting that his creation was the preferred choice in London and rapidly gaining favor in the U.S.

The 1920s fashion of wearing a full-dress waistcoat with the informal dinner jacket remained popular in London and France at the decade’s opening thanks to its frequent appearance on the Prince at Continental resorts. However, by autumn 1933 the inaugural issue of Esquire was reporting that “The white waistcoat has at last been allowed to rejoin its lawful but long estranged mate, the tailcoat, and the new dinner jackets are matched with a waistcoat of the jacket material, with dull grosgrain lapel facing.” The renewed popularity of the tailcoat in the latter part of the decade further reduced the appeal of the mixed-breed combination although some etiquette experts would continue to recommend it as a formal middle ground for decades to come.

In the mid-1930s some of the more avant-garde dressers of the era chose to bypass the traditional black and white options altogether and augmented their tuxedos with colored silk waistcoats.

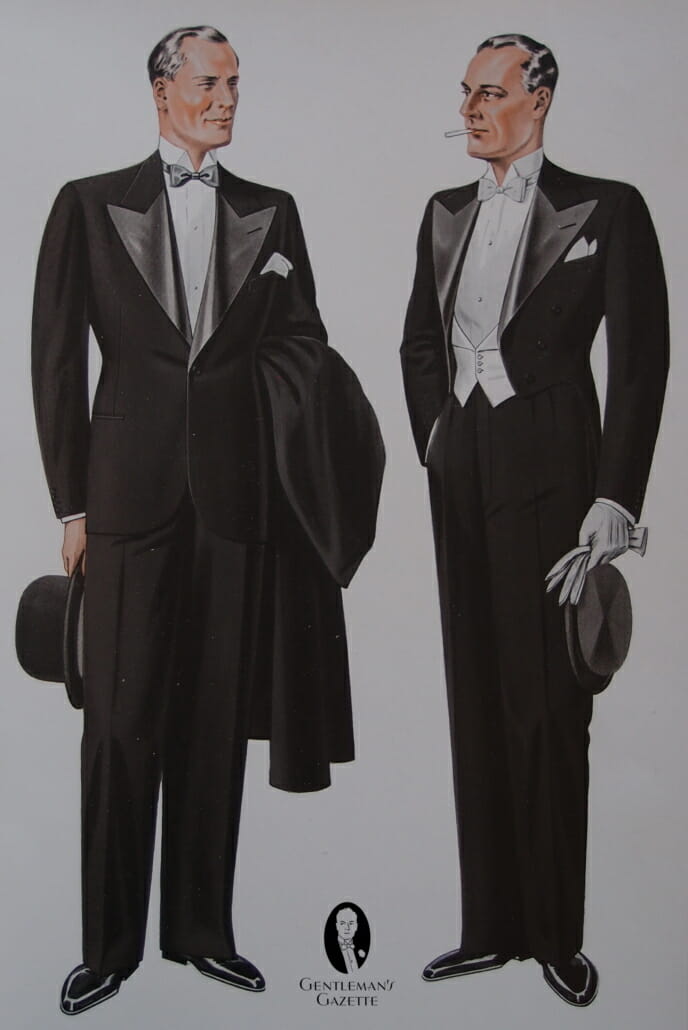

The Dress Suit: Fickleness of Fashion

Not even the century-old dress suit was immune from the sartorial exuberance of the times. “Tailcoats used to be like Fords,” wrote Esquire in 1936, “it was a point of pride that the model was seldom changed.” Now men were being inundated with menswear articles and ads stressing the need to stay abreast of the latest full-dress fashions or risk social stigmatization.

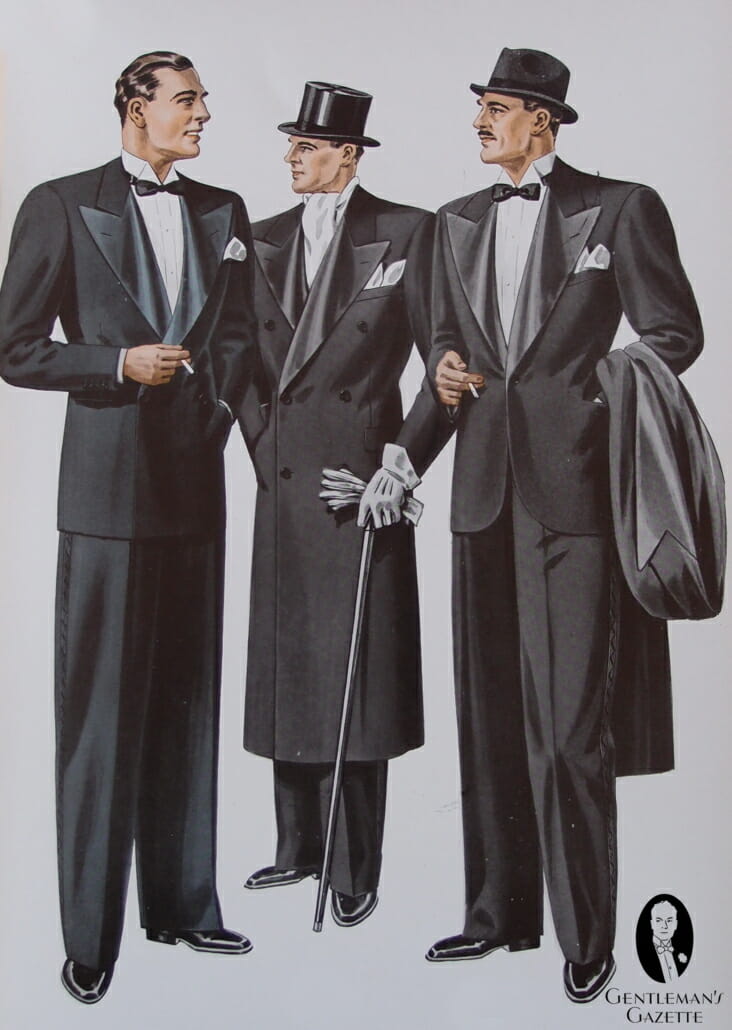

In the early years, there were two distinct styles of evening tailcoats as summarized in a 1932 Men’s Wear report. The British style featured a high waistline and broad shoulders with lots of drape (extra fullness on the chest and over the shoulder blades). In contrast, the American coat had a slightly lower waist, natural shoulders, and no drape. The British look gradually dominated due in no small part to its patronage by the Prince of Wales whose tailor also liked to employ short stubby lapels to further create a vertically elongating effect. False cuffs, lack of a breast pocket and silk cloth buttons instead of bone were other popular trends that emerged from London’s exclusive West End during the early decade. Also notable was the return of the dégagé shawl collar as an allowable alternative to the peak lapel.

Some of the more extreme developments began to fall out of favor in the years following the Prince’s 1936 abdication. By 1937 broad, stubby lapels were losing popularity and by 1940 Esquire was advising men to stick to tradition to avoid being mistaken for bandmasters, “a tribe noted for wasp waistlines, barn-broad shoulders and Himalayan high rise trousers”.

Throughout the decade full-dress trouser braids were still two medium-wide stripes or one very wide stripe although the former style was becoming more common.

Full-Dress Linens for Shirts & Waistcoats

Not content to simply improve the comfort of the full-dress waistcoat, the Prince of Wales also upped the ante on its style. Like the full-dress shirt’s studs and links, the waistcoat’s buttons were traditionally made of pearl in order to blend in with the garment’s white fabric. Consequently, when the Prince began appearing at London’s exclusive Embassy Club with black waistcoat buttons well-dressed men took notice. The fad quickly spread to America and soon other colors were also allowable provided they were “not too showy.” Single-breasted models were more popular than double-breasted ones at this time but His Royal Highness was happy to modify both. He not only exported day wear’s “W” shaped double-breasted bottom to full evening dress but also introduced rounded points as well as straight-bottom models without revers(lapels).

Above the waistcoat, the Prince favored a tall shirt collar which necessitated a wide opening and very broad tabs that were slightly wider than the bow tie. Plain linen bosoms remained popular during the era despite the growing trend for the shirt front, waistcoat and bow tie to be made of matching piqué.

The Rise of Informal Jackets and Shirts

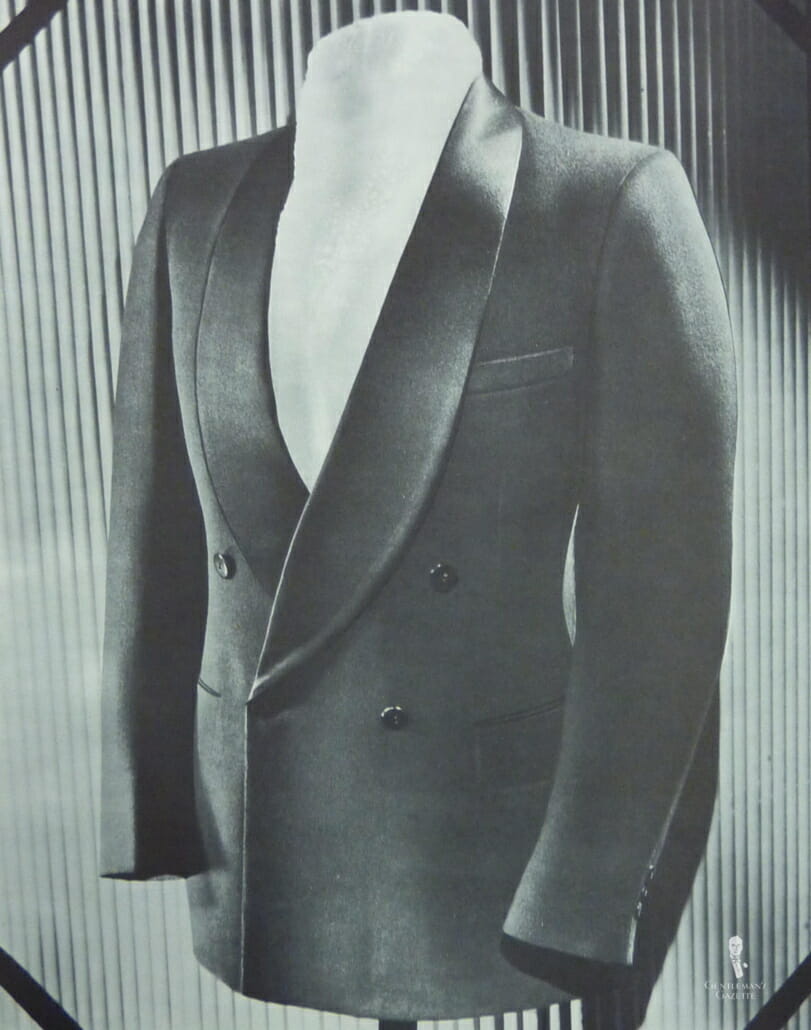

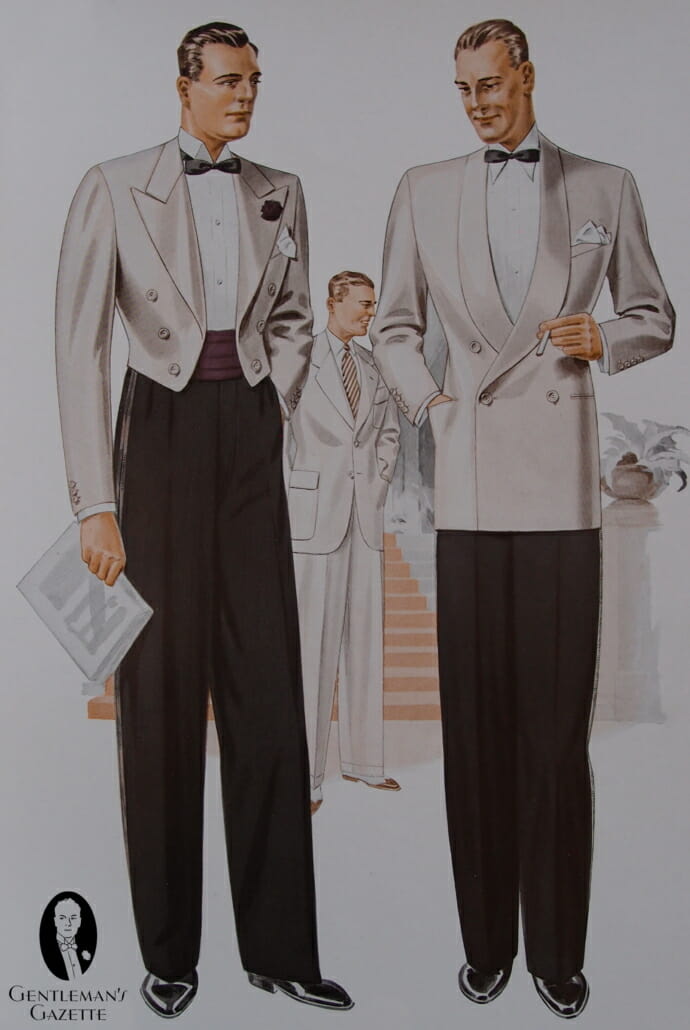

Previously considered too informal for evening wear due to its lack of accompanying waistcoat, the double-breasted dinner jacket’s popularity skyrocketed in the early thirties thanks once again to Britain’s royal paragon of menswear. The future Duke of Windsor invariably paired the swank coat with a soft-front pleated evening shirt featuring attached turndown collar and French cuffs rather than the traditional starched front shirt with detachable wing collar and single cuffs. The overall result, explains renowned haberdasher Alan Flusser, was a look that “brought a new level of informality to the traditional dinner jacket – but with no lowering of the standards that separated those who dressed correctly from those who simply dressed up.”

Although period etiquette experts made sure to limit the appropriateness of these innovations to the most informal of occasions – summer evenings, in particular – the new jacket model nonetheless rivaled the popularity of the single-breasted standard by 1935. It was often midnight blue and its lapels were usually peaked. As for the contemporary shirt style, the November 1937 issue of Esquire noted that the turndown collar had superseded the traditional wing collar by the mid thirties and was “now virtually standard for informal wear”.

Back in England, London shirtmakers devised a novel variant that was dressier than informal soft-front shirts yet more comfortable than the formal stiff-front option. The resulting marcella shirt was an elegant compromise consisting of a semi-stiff bosom fashioned out of formal piqué with a matching turndown collar and cuffs.

Other Style Trends

There was seemingly no end to the appetite for flourishes in thirties evening fashion extending down to the smallest details:

- dull or ribbed silk facings became preferred as shiny satin lapels were increasingly associated with ready-to-wear apparel

- the semi-butterfly was the favored bow tie shape although the rounded tie, pointed tie and narrow straight bat tie were also acceptable

- the black bow tie’s fabric now matched the dinner jacket’s lapel facings

- the white gardenia or carnation was the boutonniere of choice for traditionalists but the Prince of Wales-inspired clover-red carnation was increasingly popular among young men; by the late 1930s the blue cornflower was added to the mix

- for full dress the pocket watch was worn with a key chain in the early years then later “the old fashioned Georgian seal watch fob has returned”

- the black or midnight blue homburg became standard headwear with dinner suits in both England and the U.S.

Warm-Weather Black Tie Heats Up

The decade’s final innovation of note is one of the few that were not inspired by the Prince. Instead, it was originated by well-heeled Americans and Britons seeking a cooler alternative to the heavy, heat-absorbing black dinner suit when wintering in tropical climes.

The Mess Jacket

In late 1931 fashion reporters at American tropical resorts noted a new vogue among socialites for the white mess jacket, a civilian counterpart to military formal wear that resembled a tailcoat cut off at the waistline. Apparel Arts explained that the jacketoriginated as evening wear for British naval officers “but by its adoption by well-dressed Americans for wear aboard their yachts and at smart Palm Beach evening functions, it is accepted as being correct.” With the sanction of high society, the trendy garment soon became all the rage.

At first, the jacket was made either in gabardine, duck, or a washable material and had self-faced peaked lapels and front buttons. It was worn with a waistcoat of the same material, a wing collar formal shirt and high-rise dress trousers of black or midnight blue without back pockets. The bow tie and accessories were as per standard informal evening wear. A couple of years later a “smarter”, more informal shawl collar variation appeared sans buttons or breast pocket. It was appropriately paired with a soft-front turndown collar shirt and the recently (re)introduced cummerbund.

Then, almost as quickly as it had appeared, the mess jacket fell out of favor. Its primary disadvantage was that the cut was unbecoming to anyone with a less-than athletic build. Its second drawback was that it was rapidly adopted as a universal uniform for bellhops and jazz bands and few gentlemen of any fitness level wished to be mistaken for hired help or entertainers.

White Dinner Jacket

White dinner jackets premiered alongside the mess jacket in resorts like Palm Beach and Cannes, albeit with much less fanfare. Constructed of cotton drill, linen or silk they were originally worn with either black or white trousers of tropical weight wool. Their popularity at tropical locales grew slowly but surely and by the time the mess jacket had become passé in 1936 they were as common as traditional dark coats. In its August 1936 issue, Esquire defined the quintessential warm-weather formal evening wardrobe:

This year, the big swing is to single- or double-breasted [light colored] dinner jackets, collar and self lapel facings. These are worn with [black] tropical dress trousers, patent leather oxfords or pumps, a white, soft shirt with either soft or laundered collar and a black dress tie.

A cummerbund was also required when wearing a single-breasted jacket and although there were no specific rules for lapel style, shawl collars were the norm.

Warm-Weather Color

The acceptance of white jackets paved the way for other colors in summer evening coats and soon hues such as plum, dark green, wine and bright blue were being worn on the moonlit patios of Palm Beach. The next logical development was coordinated accessories and dark red was the favorite choice for bow ties, cummerbunds, hosiery clocks and boutonnieres. Pocket squares were also frequently used to add a splash of flair but only when the boutonniere was white.

The addition of subtle colored touches to the black and white summer palette was so successful that many of these accessories began to migrate to traditional dark dinner suits as the decade progressed.

Return of the Cummerbund

The reappearance in the late 1920s of the newly modified cummerbund fared much better thanks largely to its pairing with the popular mess jacket. By 1937 The New Etiquette was describing the garment as a “popular and chic” waist covering for informal evening wear at resorts. “It is meant for hot weather to obviate the necessity of having the harness of a waistcoat over the shoulder and back when it might be uncomfortably warm. On the right people at the right time, it is decorative and correctly in the spirit of colorful gaiety.”

As the author alluded, the cummerbund could be used to infuse warm-weather formal wear with color and even patterns. Most often though, black silk continued to be de rigueur for waist coverings worn with the white dinner jacket. The pleated formal sash could also be correctly matched with a black tuxedo according to the book’s author, but only when those tuxedos were worn at resorts; the acceptance of cummerbunds year round was still at least a decade away.

Classic Etiquette: Distinguishing Formal, Semi-Formal, and Informal

Formal Evening Wear

Paradoxically, while evening wear’s attire grew more casual its protocol backtracked towards pre-war formality as the Depression progressed. “The traditional standard of a tailed coat and white tie being necessary for wear to any formal affair attended by ladies holds true today” reported the Fort Worth Star Telegram in September 1935. “Undergraduates at the universities are responsible to a certain extent for upholding again the cannon of correct dress. Tailed coats reign at proms, and dinner jackets no longer are ‘made to do’.” By January 1940 the Ivy League influence had become so prevalent that “tails have pretty well replaced the dinner jacket at most places of celebration” said Esquire.

Informal / Semi-Formal Evening Wear

By November 1936, Esquire was instructing readers that the dinner coat was generally only proper “on shipboard, in the tropics, for dinner parties at home, theater parties and club and stag affairs.” This return to Edwardian strictures may have demoted the dinner jacket’s status in theory but in the pages of Apparel Arts and Esquire, the ensemble was promoted to the newly coined rank of semi-formal. This compromise categorization was fitting considering that the so-called “informal” tuxedo had been appearing regularly at relatively formal functions since the end of the First World War.

Regardless of the terminology employed, it was universally accepted that recent innovations in evening fashions had created a new sub-hierarchy. At the top of the tuxedo scale were the very formal single-breasted jacket of black or midnight blue – the only correct colors for dressing in town – and the wing collar shirt. At the bottom of the ladder were warm-weather jackets, suitable only for country summers and the tropics. Situated somewhere in between were the double-breasted jacket and turndown collar shirt originally classified as casual but increasingly acceptable at all semi-formal occasions thanks to their soaring popularity.

While British etiquette authorities acknowledged a similar dinner suit hierarchy they continued to define evening wear as being either “full dress” or a variant of “dinner dress”; in England, there was no such thing as being half formal.

A Black and White Code

Amidst the ongoing confusion of exactly what constituted “formal” in this modern era – some American sources were even beginning to use it as a blanket term for all evening wear – there arose a more colloquial designation for the tailcoat and tuxedo. By focusing on the outfits’ obvious physical differences White Tie and Black Tiecircumvented the formal guessing game and gradually became part of the common vocabulary.

Golden Sunset: The End of an Era

By the conclusion of the 1930s, the tuxedo had reached its apex in both popularity and style. As Alan Flusser summarizes in Style and the Man:

No other era could have produced such a sartorial success. Each step of the dinner jacket’s evolution was measured by the perfection of the outfit it intended to replace – the grandfather of male elegance, the tailcoat, and white tie . . . The new dinner jacket projected a level of stature and class equal to that of its starched progenitor, albeit while providing considerably more comfort.

Just as the previous war had ended the pre-eminence of the tailcoat, so too would World War II bring a close to the dinner jacket’s golden age. Although the tuxedo’s stylistic innovations would safely survive the ensuing conflict, its status as standard evening attire would continually erode in the increasingly informal world that emerged after 1945.

Formal Facts & Style Icons

Formal Facts: Tuxedo Rentals become popular

Clothing rental (clothing hire in the UK) made formal wear vastly more accessible to the average person and became a became a multi-million dollar industry in the process. The company featured in this 1937 Toronto yellow pages ad had been in the business since 1918 and is now a national chain known as Freeman Formal wear.

Prince of Wales, King Edward VIII, Duke of Windsor

The Prince of Wales became King Edward VIII in January 1936. However, he abdicated the throne only eleven months later to marry American divorcée Wallis Simpson. In 1937, he received the title with which he is most commonly associated: Duke of Windsor.

As a big proponent of the more “casual” black tie outfit, he is known for having word splendid evening ensembles.

Style Icons: Fred Astaire

Fred Astaire was not only a star of Hollywood musicals but also an impeccable dresser. His custom tailcoats were so well tailored they remained perfectly placed throughout the most exuberant of dance routines. One of his most popular films was in the 1935 smash hit Top Hat which featured the Irving Berlin song “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails”

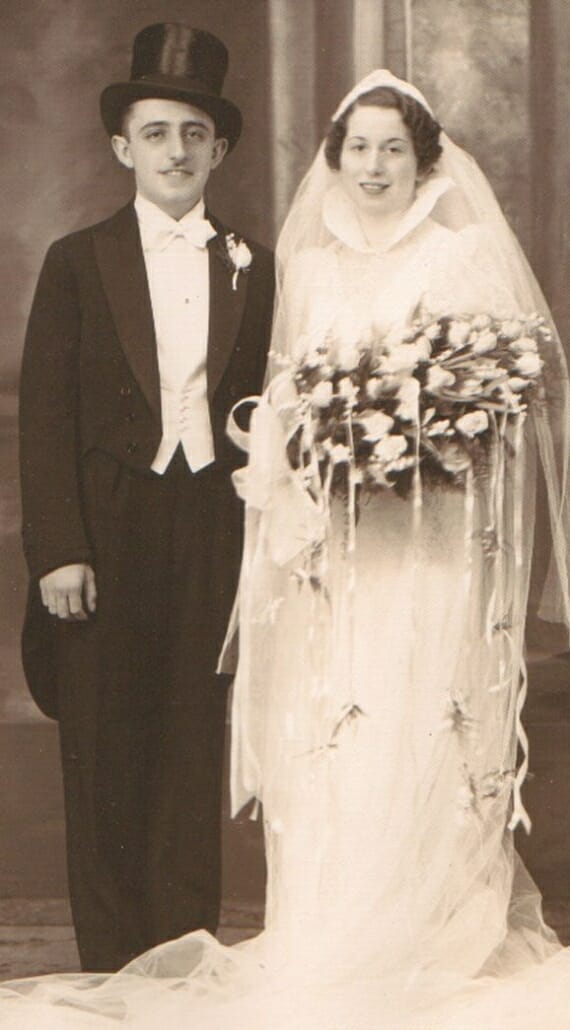

Formal Facts Evening Weddings

Although unknown in New York, evening weddings were fashionable in other U.S. cities. Etiquette authorities continued to mandate full dress but Esquire articles and vintage photos reveal an increasing acceptance of the tuxedo. See Vintage Evening Weddings for details.

Formal Facts: Prom

The American high-school prom descended from college cotillions and society debutante balls in the 1920s and became widely popular in the 1930s. These rituals for molding adolescents into respectable citizens included the trading of youthful apparel for adult evening wear.

Formal Facts: Apparel Arts, Esquire, Herrenjournal…

Men’s Fashion magazines as well as tailoring periodicals contained lots of photos and illustrations. In the US, Apparel Arts was a clothing wholesale buyers and haberdashers publication that debuted in 1931 and was published twice a year at first, and then once a quarter. It was so popular with retailers’ customers that the publishers launched Esquire in 1933 as a male equivalent of Vogue featuring pictorials from its parent publication.

Both were promoted by the same publisher, so half a year before the latest fashions would be seen in Esquire, they would appear in Apparel Arts. That way, a men interested in fashion could go to the local store and get the latest fashion. In 1957, the magazine changed from Apparel Arts to Gentleman’s Quarterly, which is now geared towards the consumer and called GQ.

Together with the tailoring trade magazine Men’s Wear, these are the foremost resources for 1930s American men’s fashion.

In Europe, there were numerous other menswear magazines such as the Herrenjournal in Germany, and that promoted classic men’s style.

Formal Facts: Vintage Warm-Weather Black Tie

For much more on the mess jacket and white dinner jacket outfits of the 1930s and ’40s see the Vintage Warm-Weather Black Tie page.

Formal Diplomacy

In many countries, White Tie is the 20th-century version of the ornate diplomatic uniforms worn by ambassadors and their staff at public occasions since around 1800 and patterned on European court dress.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie