We appear to be on the threshold of a period rivaled only by the 1930s for distinguished wearables. A better period, in fact, because today there’s more variety and much more comfort in formal attire.

Elegance: A Quality Guide to Menswear (1985)

Return to Elegance

The conservative wave that had begun its approach in the late 1970s hit America’s shores with full force in the 1980s. Marriage and formal weddings were once again fashionable, etiquette books had become bestsellers and Victorian traditions were being rediscovered by many. At the same time, baby boomers were now young upwardly mobile professionals with a sense of entitlement to the better things in life. By having children at a later age, and taking on significant debt, they were able to lavish themselves with luxury goods and live the refined lifestyle they craved. There could not have been a better confluence of events for the return of formal elegance.

Black-Tie Boom

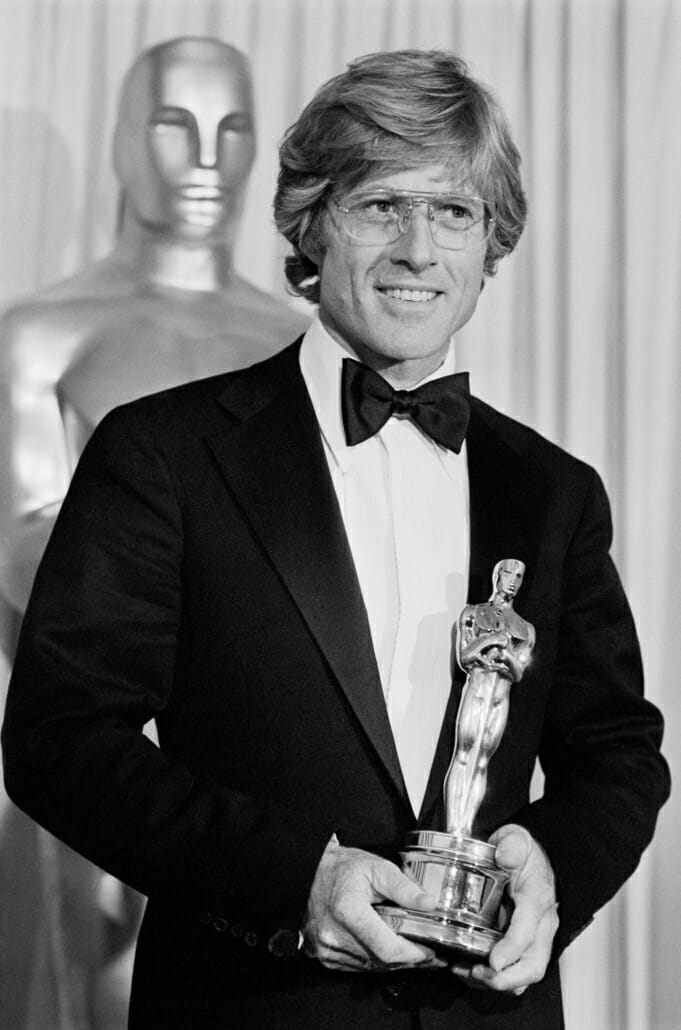

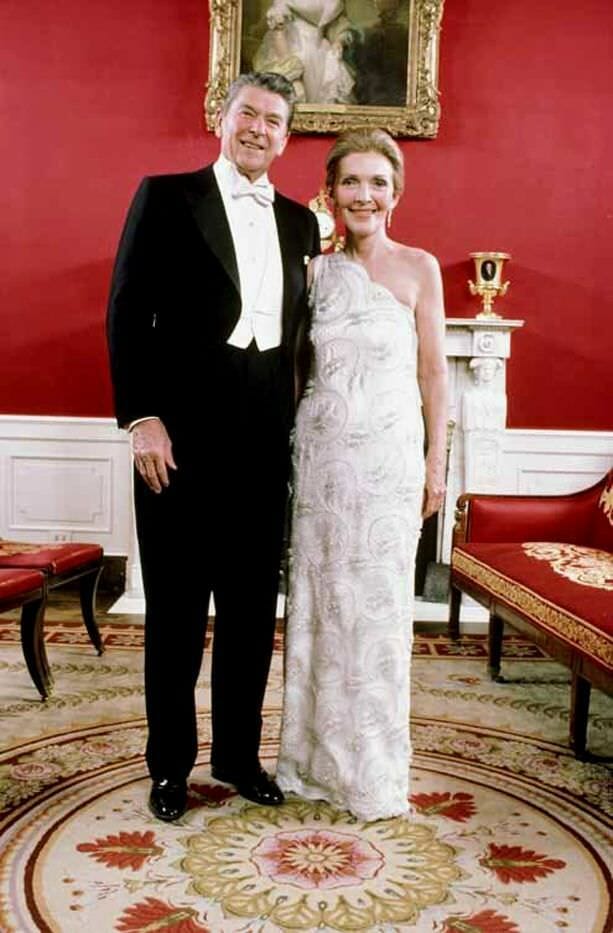

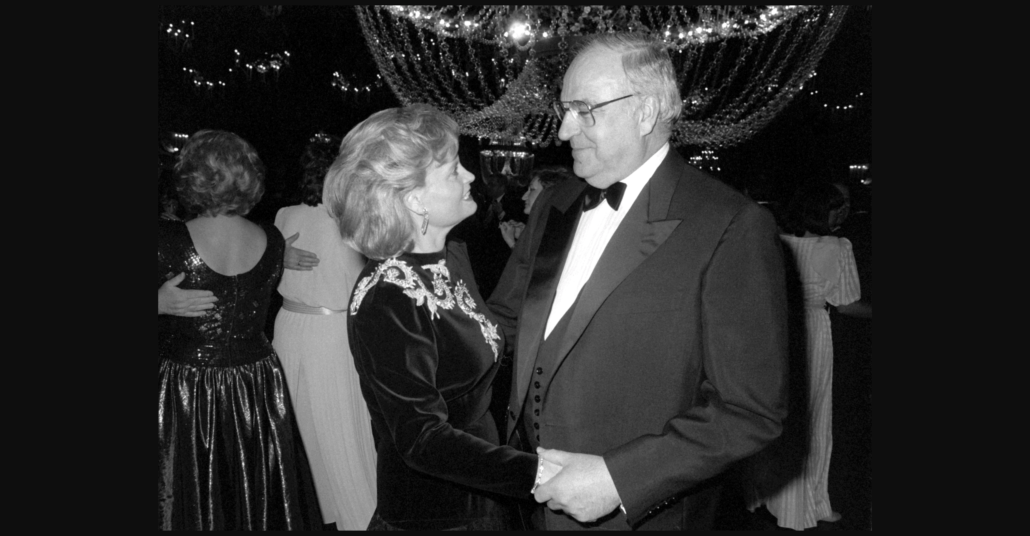

The classic tuxedo’s emerging renaissance of the late seventies quickly blossomed into a mainstream phenomenon thanks in part to a certain old-school Hollywood actor-cum-president. Elected in 1980, Ronald Reagan popularized not just conservative politics but also conservative fashions. “He wears formal wear often and looks good in it,” observed the president of formalwear manufacturer Lord West in 1985. “We haven’t had this influence in formal wear since Kennedy”. Tuxedos were back in black, not just in the pages of men’s fashion magazines but also on the backs of just about every groomsman in the country. A corresponding increase in the popularity of black-tie affairs prompted a Virginia newspaper to observe in 1988 that “what was confined to a September to May party circuit has now become a round of year-round social events.”

By 1985 mass-market formalwear sales and rentals had soared to $600 million, up fifty per cent from just five years earlier. For the more affluent gentleman profiting from the economic orgy that inspired the now-classic 1987 film Wall Street, it was not unusual to attend over a dozen black-tie occasions per year decked out in a $2,500 Dimitri dinner suit or $975 Versace silk waistcoat. Not even the early nineties recession could halt the formal juggernaut: by 1993 formalwear specialists were reporting that one in every four tuxedos was being purchased rather than rented, compared with only one in nine during the late 1970s.

Early ‘80s Style: New Wave Alternatives

The New Wave Look

As the seventies drew to a close black tie began to take on contemporary embellishments that would eventually become identified with American New Wave fashions. The omnipresent wing collar shirt tended to have miniscule tabs, the pre-tied bow tie was usually not much wider than its band and the jacket lapels and cummerbund were similarly narrow. Bright red was the color of choice for these skinny accessories as well as for the newly rediscovered pocket square.

A trendy alternative for young men was the spencer jacket. This tail-less tailcoat was popular for casual wear throughout the decade and in the mid-eighties made the transition to formal attire where it was usually constructed of black wool with satin-faced peak or shawl lapels and was buttoned in front. The jacket was worn with trousers of matching or different material and was accessorized with a cummerbund.

Of course not every formal dresser wanted to look like the quintessential eighties wedding usher. For more conservative functions discriminating men could choose from tasteful contemporary flourishes such as velvet or alpaca dinner jackets, black-on-black patterned tuxedos and pumps of velvet or suede.

Informal Formal Wear

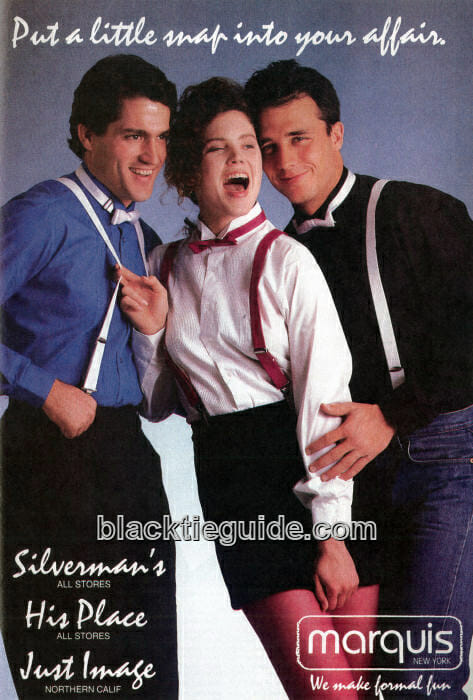

One of the most distinctive traits of New Wave fashion was its collage style of dressing wherein disparate articles of clothing were layered together to create a unique look that defied standard categorization. As part of this fashion, designers and retailers frequently combined casual clothes with formal attire to create various mélanges that spanned the range of dressiness.

At the more casual end of the spectrum everyday clothing was infused with a formal twist by dressing up a sports jacket and parachute pants with a wing collar shirt, for example, resulting in a sort of “formal casual” look (see sidebar). At the other end of the scale was “informal formal”, a popular term in the pages of GQ during the early eighties. The mindset behind this dress-down approach seemed to be that as long as you were wearing a wing collar shirt and a bow tie then your outfit qualified as formal, even if said shirt sported regular buttons and colored stripes.

Later Style: Black & White (Tie) Formality

“Informal formal” aside, the New Wave formal variations of the early 1980s differed significantly from the tampering of the previous twenty five years in that they focused on adapting traditional evening clothes rather than reinventing or even discarding them. This was indicative of the continuing influence of the classic renaissance that had begun in the late seventies, described by GQ in its annual formal wear review of December 1984:

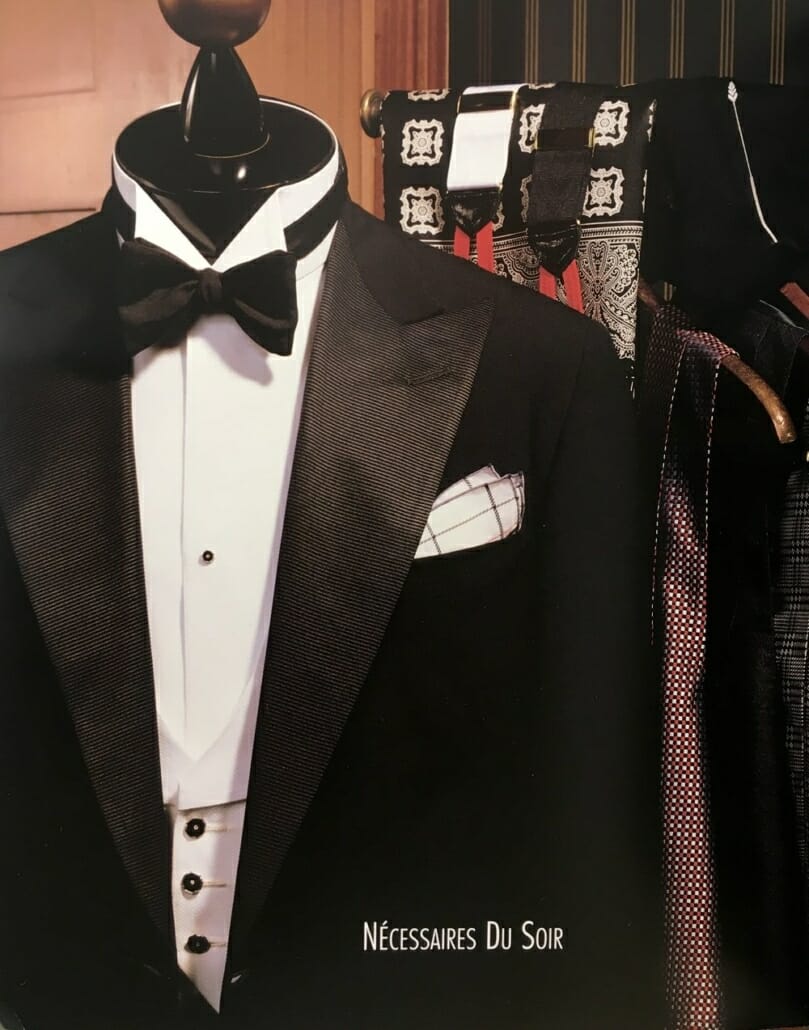

To be sure, the Thirties remain the inspiration: double-breasted dinner jackets with peaked satin or grosgrain lapels; dress waistcoats of cotton piqué or fine worsted; morning trousers and woven-silk cummerbunds; bib-front stiff-wing -collared formal shirts. The accessories – from watch fobs and stickpins to deftly folded, crisp linen pocket square – also evoke another era.

As the decade progressed formalwear styling became only more conventional. In its December 1987 annual formal wear review GQ noted that:

Black tie, of late, has returned to just that, black ties. The red, yellow and paisley of a few years ago have bowed out, for at least the time being. With single-breasted dinner jackets, the waistcoat – especially the odd (nonmatching) waistcoat continues to gain ground on the cummerbund. This further reflects formal wear’s overall emphasis on its English roots.

A 1993 Cigar Aficionado article titled “In Praise of Elegance” noted how the eighties homage to the dinner jacket’s golden age had by that point evolved into a virtual recreation of the era:

If anything, modern tuxedo designs draw inspiration from those worn by the likes of Humphrey Bogart, Fred Astaire and William Powell in the ’30s: wide, sweeping satin or grosgrain lapels, often double-breasted with either peaked or shawl lapels; broad, padded shoulders, a slight suppression to the waist and amply cut out, deeply pleated trousers for sweep and swagger.

Thanks to the proliferation of black-tie summer affairs, the ivory dinner jacket had also been resurrected with all its stylish aplomb by the late eighties. Suspenders were back in vogue too, now that the self-supporting waistband was declining in popularity. And the modern style of wing collar shirt (pleated front, attached collar) had become the status quo by the end of the seventies; apparently the turndown collar was too pedestrian for yuppie tastes.

Ironically, the informal notched lapel which had virtually disappeared from the dinner jacket in the unconventional 1970s returned to popularity during this otherwise conservative period. In fact, in 1988 the revised edition of Dress for Success reported that it was “the model worn by most executives today.”

White Tie Renaissance

The yuppie craving for elegance, status and tradition was such that even the long-forgotten full-dress ensemble emerged from sartorial purgatory. The December 1980 GQ contained a two-page spread that featured not one or two, but five models clad in white tie. Then just one month later newly-elected Ronald Reagan appeared at his inaugural balls in full-dress splendor, the first U.S. president to do so in twenty years. Even the piqué full-dress shirt with detachable collar – the ne-plus-ultra of formal shirts – had returned to the spotlight in menswear magazines.

Sadly, white tie’s bright star of the early eighties would turn out to be its final supernova. President Reagan’s decision to downgrade to black tie for his second inaugural ball in 1985 signaled the end of the brief renaissance and the ultra-formal dress code once again returned to near-obscurity while its components were relegated to bastardized semi-formal outfits.

Yuppie Era Etiquette

Attire

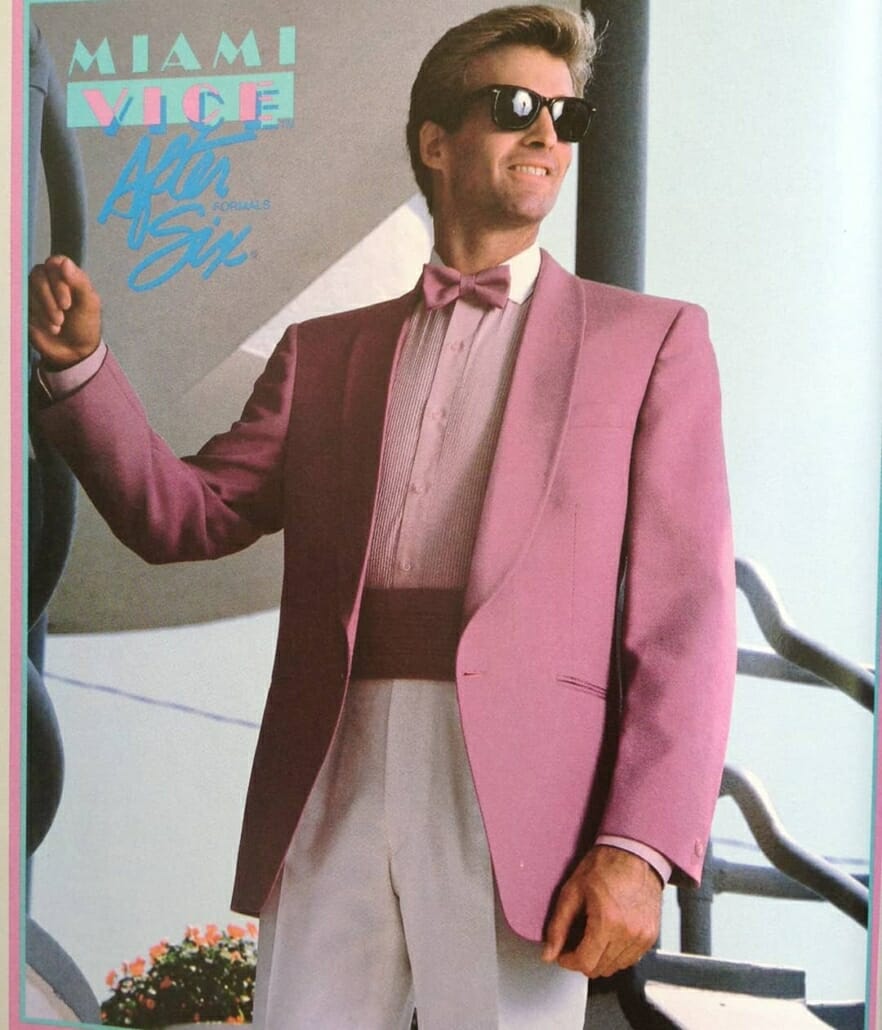

Just as in the late seventies, evening wear’s return to classic styling did not necessarily coincide with a return to classic etiquette. Cross-pollinating black-tie attire with white-tie tailcoats or morning-dress trousers and referring to the tailcoat as a “full dress tuxedo” were just some examples of how GQ and its upscale advertisers continued the muddying of formal dress codes that had begun in the previous decade. Far worse was the rental clothing being marketed to mainstream baby boomers that had grown up devoid of a formal education. To these clueless customers the formalwear industry promoted highly unconventional wedding and prom attire such as all-white tailcoat outfits, Miami Vice pastel dinner jackets and a rainbow of matching bow ties and cummerbunds.

As for the traditional etiquette experts, just when the extraordinary formalwear revival made their guidance more essential than ever, the 1980 Amy Vanderbilt and 1984 Emily Post editions radically scaled back their black-tie advice. To the former book’s credit, its previous allowances for unconventional colors and flourishes at summer ceremonies had now been replaced with advice to stick to the traditional white dinner jacket. The latter author, on the other hand, continued to make exceptions for colored and patterned jackets at other less formal occasions, especially in summer.

Into this void of black-tie sartorial counsel stepped two paragons of masculine style. In 1985 menswear designer Alan Flusser published Clothes and the Man, the same year that G. Bruce Boyer, men’s fashion editor for Town & Country, issued Elegance: A Quality Guide to Menswear. By drawing on principles established in the golden age of male attire, both writers provided readers with more detail about proper formal wear than anything published since that era. Thus, at a time when most fashion authorities were simply reporting on what was currently acceptable, Flusser and Boyer dared to dictate what was traditionally correct.

Dress Codes

While the vast spectrum of attire that had recently been considered acceptable for black-tie affairs had narrowed significantly by the eighties, the general concept of a sliding scale approach to formality had become firmly entrenched in modern etiquette. “In the face of bent, if not broken, fashion dictates,” advised GQ in December 1982, “let the event determine the liberties suited for veering away from evening clothes’ classic rigidity.” Consequently, the arrival of Black Tie Optional and Black Tie Requested dress codes in the late seventies and early eighties was likely as much an attempt to help guests situate a formal occasion on this sliding scale it was a (misguided) effort to avoid alienating more casually inclined invitees.

The Creative Black Tie code would not be far behind considering the formal attire featured in a 1983 GQ pictorial that included a traditional dinner jacket and formal shirt paired with distinctly unconventional jeans, cowboy boots and a black ten-gallon hat. “The answer to the summons of ‘black tie’ is no longer obvious,” said the writers. “Formal elegance is, more than ever, a personal decision, notwithstanding, of course, the requisite nod, if not bow, to the nature of the occasion.”

Occasion

Regardless of how it was worded, the Black Tie code was appearing on more invitations than ever thus “ushering formal dressing into a twelve month affair” according to GQ. The increased popularity of dressy weddings and proms in particular helped generate one of the formalwear industry’s best seasons ever in 1985. ”10 years ago we were lucky if 50 percent of first-time grooms wore one,” said the president of Lord West in a 1986 New York Times interview. “Today,” the article continued, “85 percent of first-time grooms wear tuxedos, as do the 6.5 ushers in the average wedding party.” Black-tie charity galas were also experiencing tremendous growth as private fund-raising dinners stepped in to compensate for the Reagan-era cutbacks on social spending.

Just as significantly, black tie’s rising popularity also included occasions considered formal solely by tradition. “Used to be that you had to wait for a prom, a wedding, or some other occasion at which you wished you were dead,” remarked the authors of Esquire Etiquette in 1987, “but that’s all changed now. It’s perfectly acceptable these days to don a tuxedo for the theater, the opera, the ballet or even dinner at a nice restaurant.” A case in point was the early nineties advent of hugely popular “smokers”, tony soirées centered around cocktails and cigars that often featured a black-tie dress code to complement the evening’s elegance.

The Tuxedo’s Centennial

The black-tie boom of the 1980s was a fitting tribute to the 100th anniversary of the popular introduction of the dinner jacket. It had certainly been quite a century for the unassuming tuxedo. Its usage had graduated from the aristocracy’s informal tailcoat alternative to their standard evening attire then became special-occasion clothing for mainstream society. Its components had concurrently evolved from heavy wool suits with cardboard stiff shirts to lightweight jackets with soft chemises, devolved into pasteled and ruffled aberrations then were reborn in all their classic glory.

Amazingly, black tie had somehow managed to survive the adversity of post-war informality, counterculture rebellion and yuppie ignorance. Now, as the new millennium drew near, the dress code was set to face its next great challenge: GenX adulteration.

Formal Facts

Formal Casual

The mix-and-mismatch trend of the early ’80s saw items formerly associated with evening wear adapted for everyday wear. For the new generation, pairing minuscule wing collars and bow ties with street clothes no doubt muddied black tie’s traditional protocol and diluted its historic prestige.

The Spencer Jacket

The formal Spencer jacket actually traces its roots to the 1700s and was the inspiration for the early 1930s civilian mess jacket fad. See Contemporary Alternatives for an overview of its 200-year history.

Rental Formal Wear

The formal wear revival manifested itself in a much less classic manner for renters than it did for buyers: the most popular formal outfit for proms and weddings in 1985 and 1986 was the white tailcoat aberration.

Updating a Classic – The Wing Collar Shirt

In the early ’90s, premium shirtmakers began offering formal shirts with large swept-back tabs in front and a hem in the back to help hide the bow tie’s band. Needless to say, these innovations disappeared as quickly as they showed up. After all, there is no need to mess with the classics.

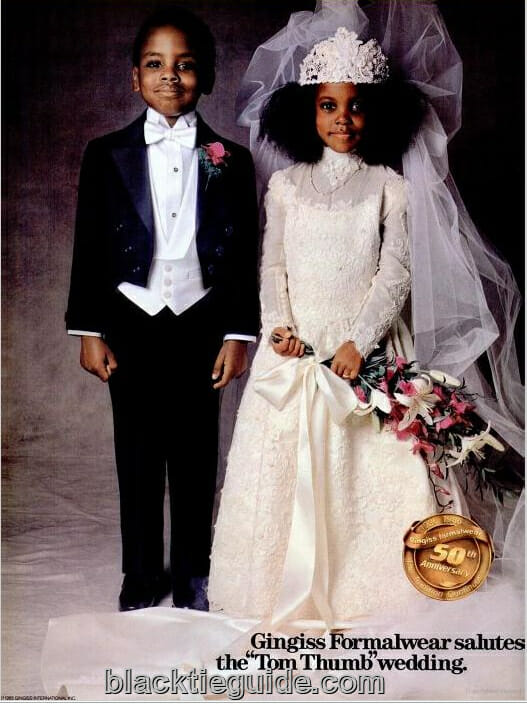

Tom Thumb Weddings

Inspired by the marriage ceremony of famous little person General Tom Thumb in 1863, American schools and churches began to stage wedding pageants using small children in the roles of the wedding party. These continued to be presented fairly regularly until the 1970s, often as fundraisers. This 1986 formal wear ad appears to be cashing in on the era’s black-tie boom by attempting to revive the tradition.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie