Dress, over the habitable globe, has ever been, and is, regulated by habit except in civilized Europe, where that staid regulator is fast getting superseded by a turn-coat whirligig maniac called Fashion, that is always changing and running into extremes, being scarcely ever detected in one form before it is out of it.

The Whole Art of Dress (1830)

Changing Tailcoat Cuts

As previously mentioned, the tailcoat’s origins lie in the adaptation of the frock for comfort and style. In the late 1700s, the front of the long frock’s skirt (the portion below the waist) was increasingly cut away to make the coat more practical for horseback riding. By the end of the century, all that was left of the skirt was its rear which was divided in half by a long center vent – once again, for riding comfort – resulting in two “coattails”. This new “swallowtail-coat” or, more simply, “tail-coat” was soon adopted as the new dress coat for day and evening.

- Changing Tailcoat Cuts

- Common Tailcoat Colors

- Development of the Tailcoat Lapel

- Other Notable Tailcoat Details Develop

- The Waistcoat: Any Color Goes

- Breeches, Pantaloons, and Trousers, Oh My

- The Social & Economic Significance of a White Shirt

- Regency Neckwear Varities

- Footwear: Pumps, Boots, and Stockings

- Evolution of the Evening Hat

- Kid, and Other Types, of Gloves

- Regency Accessories

- The Foundation is Set

- Formal Facts & Myths

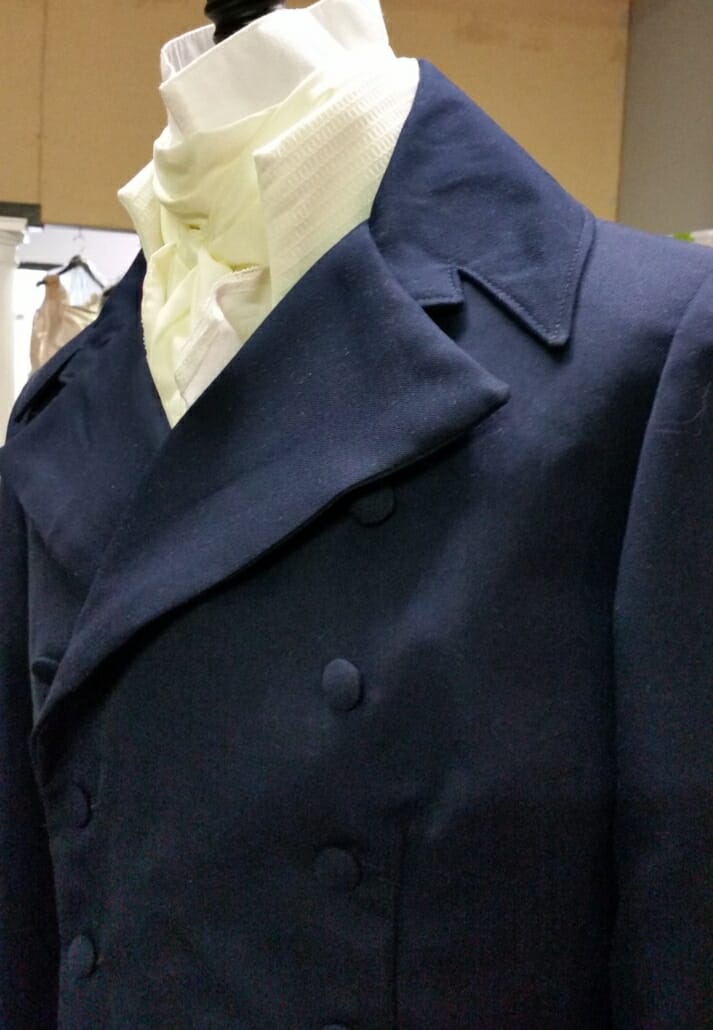

Both types of dress coat could be single or double-breasted. At first, they were worn either open or closed but the open style became the most popular for evening coats so as to better show off the waistcoat, shirt, and cravat and by the 1820s, evening tailcoats were being deliberately cut so that the fronts could not even meet. The coat’s front was cut high and its tails displayed moderate variations in shape and length during the Regency period.

Common Tailcoat Colors

The colors of the first evening tailcoats were often black or the dark shades of blue, green, claret, and brown.

Soon, dark blue models with gilt buttons and black with covered buttons were the only acceptable choices and the latter version was the norm by the end of the first decade.

Development of the Tailcoat Lapel

A significant tailoring detail was the separation of a coat’s collar and lapels for the first time, with the lapels being folded back as if from the lining of the coat.

The point where they met was marked with a notch in the distinctive M shape of the period or in a simple V shape. On evening tailcoats, the collar was often velvet but lapels were not yet silk lined as they are now.

Other Notable Tailcoat Details Develop

Other notable features of early tailcoats were two buttons on the small of the back (and buttonholes at the end of the tails) originally added so the tails could be folded up and buttoned to the back of the coat when in the saddle.

And thanks to Beau Brummell and his tailor, pockets were hidden in the folds of these tails so that they would not interfere with the lie of the coat the way that traditional hip pockets did.

The Waistcoat: Any Color Goes

While the Regency daytime waistcoat could be either single or double-breasted, the evening version was always single-breasted. It was cut straight at the bottom and in the 1820s collars were introduced that were either notched or “en schal” (shawl).

White Marcella or plain black fabric was standard for evening waistcoats until the end of the 1820s when “all the colors of the rainbow” were being worn by dandies who also preferred embroidery and rich plain or figured silks and satins.

The Under-Waistcoat

The waistcoat grew longer in the late 1820s leading to the return of the late eighteenth century under-waistcoat. At first, this was a sparse undergarment meant to project just beyond the edges of the overlying version. It then evolved into a full-blown torso covering with lapels, decorative buttons and gorgeous colored materials designed to contrast with the upper waistcoat which was often left open at the top for better exposure.

Breeches, Pantaloons, and Trousers, Oh My

For evening dress, as with day dress, breeches and pantaloons were both acceptable. At the beginning of the century, the most popular choice was breeches that ended just below the knee. Beau Brummell preferred black silk but white or light-colored wool fabrics were quite common during the Regency.

By the 1820s, the popularity of pantaloons had relegated breeches to only the most formal of occasions and by the following decade, trousers had also become widely accepted for evening dress. Although pantaloons tended to be slightly more form-fitting than trousers, they were often indistinguishable and the two terms were apt to be used indiscriminately. Both were originally calf length in order to show the ankle and stocking then by the teens they were cut closer to the shoe and acquired straps to hold them in place and to prevent wrinkling when seated.

For day dress, these stirrups were worn under the shoe but with evening dress, they went under the foot. Evening dress pantaloons and trousers were generally of white or black kerseymere or cashmere.

The Social & Economic Significance of a White Shirt

Day and evening shirts were generally white muslin. While the choice of white material might seem entirely unremarkable today, in Beau Brummell’s time, the wearing of white shirts, waistcoats, and neckcloths was a subtle indication of a man’s wealth. In order to maintain a spotless appearance in the dirty conditions of the country or city, these easily-soiled garments would have to be changed frequently which meant hefty laundering charges affordable only by the rich.

Evening shirt-fronts were pleated and/or frilled, often asymmetrically. Collars were tall enough to stand above the cravat and were sometimes stiffened. At first, they were attached to the shirts then in the 1820s the detachable collar began to appear.

Regency Neckwear Varities

Cravat

The Regency neckcloth consisted of either a cravat or a stock.

A cravat was a large, usually starched, square or triangle of linen or silk folded into a band and wrapped around the neck. It was sometimes wrapped around a stiffener first, which was a sort of tall leather collar that often enveloped the entire neck. There were different ways to tie the cloth depending on the formality of the corresponding attire. By the 1830s it was common to tie the evening cravat in a bow although the most elegant style, “the Ball-Room”, did not feature one.

Stock

A stock was a shaped band fastened at the back of the neck with ties, a buckle or hook, and eye. According to The Cut of Men’s Clothes they were made from horsehair or buckram with leather-bound edges and were covered with velvet, satin or silk. This type of neckcloth had long been used by the military and was introduced to general society by King George IV in 1822.

The Whole Art of Dress, an 1830 guide to men’s fashion, described The Royal George style of stock as being composed of “the richest black Genoa velvet and satin” and tied into a small gordian knot with short broad ends. It was also known as the Full Dress stock because of the two other styles – the Plain Bow (or “Plain Beau”) and the Military –were not considered suitable for formal occasions.

Color

White was the obligatory color for all evening dress neckwear during this time with the notable exception of George IV’s reign when his penchant for black took precedent.

Footwear: Pumps, Boots, and Stockings

Pumps

During the Regency era, full dress differed most from day wear in that pumps were worn instead of boots. According to Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century pumps were originally worn by acrobats and running footmen (attendants who ran beside or behind the carriages of aristocrats) owing to their pliability but they were also sported for elegance. Describing this type of shoe circa 1830, it states: “The Dress Shoe, generally termed Pumps and always worn for full dress, was of Spanish leather, the sides not above 1 ½” high and 1 ½” over the toe. Tied with a small double bow of broad ribbon.” Beau Brummel was considered to have popularized this style of “thin” shoes for evening wear.

Boots

According to an 1836 British menswear periodical “varnished boots (i.e. half boots)” had by then gained favor with “dancing pumps” although this trend apparently did not meet with everyone’s approval: an American etiquette book published the same year sternly warned that “Those persons who dance in boots,–and many fools of fashion do it—degrade themselves and insult society”.

Stockings

Whether worn with breeches or pantaloons, evening dress stockings were white or natural colored silk. By the 1820s black silk was becoming a popular alternative.

Evolution of the Evening Hat

Chapeau Bras or Bicorne

At the turn of the century, the chapeau bras was the only hat for evening dress. Also known as a cocked hat, it was a crescent-shaped headpiece like the one made famous by Napoleon but was specifically designed as a collapsible hat to be carried under the arm – thus its French name “arm hat”. According to Handbook of English Costume, it was also known as an opera hat (not to be confused with the later collapsible top hat of the same name) and today it is frequently referred to as a bicorne, a general term for two-cornered hats. Regardless of its moniker, in England, the hat was black and often fringed with feathers and sometimes had a tassel at the two peaks.

Top Hat

The chapeau bras was soon limited to the extreme formality of court dress thanks to the 1812 invention of a collapsible version of the “round hat” that was popular as daywear. This novel contraption allowed gentlemen to flatten their high hats so that they could be placed under the seat when attending the opera or theatre which were popular evening pastimes.

Acceptable at first only for informal evening events, tall hat styles became increasingly popular as full-dress attire in the 1820s with the arrival in England of the French top hat. The standard top hat was made of black silk plush (a pile longer and less dense than velvet pile) or felted beaver fur while early collapsible versions were generally made of the former material.

Kid, and Other Types, of Gloves

Men’s evening gloves were usually white or buff-colored kid leather, a luxurious material that fit like a second skin. Glove protocol was quite stringent: they were to be worn at all times except supper. The exception was just as important as the rule according to an 1836 etiquette guide which declared that “nothing is more preposterous than to eat in gloves.”

Regency Accessories

Regency evening dress was form-fitting finery that held little regard for the storehousing of personal artifacts common among day clothes. A virgin white pocket-handkerchief of lawn or cambric muslin with lace trim would likely have been carried in the tails’ inner pockets since there were no visible ones elsewhere on the coat. These pouches would also have discreetly held a gentleman’s gloves when he removed them for dinner.

A pocket watch was similarly concealed in a small compartment sewn into the inner waistband of the breeches or trousers. The timepiece was accessible by means of a fob, an attached strip of decorative chain or fabric which was usually weighed down with a personal seal. Other than an occasional cravat pin there were rarely any other embellishments to be seen as shirt studs, cufflinks and boutonnieres were not yet in fashion.

The Foundation is Set

While France may have dominated women’s fashion during the nineteenth century, the superior skill of London tailors established English menswear as the standard for Europe and the New World. In the matter of evening wear, that standard consisted of Beau Brummell’s 1801 black-and-white dress code which had withstood the experimentation of the intervening years to become the status quo by the end of the Regency era in 1837.

With the passing of the crown from William IV to his niece Victoria, the British Empire would commence an unrivaled epoch of prosperity and conservatism during which Brummell’s evening fashions would evolve into a virtual uniform across the western world.

Formal Facts & Myths

Formal Facts: Formal Equestrianism

The horseback origins of the tailcoat are evident in formal equestrian attire such as the tailcoat sported in dressage competitions and the scarlet evening tails worn to hunt balls by entitled members of fox hunting clubs.

Formal Facts: Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Ebony apparel became increasingly stylish due in part to Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The popular author wore black “as a romantic gesture to show that he was a ‘blighted being'” according to menswear historian James Laver.

In his hugely successful 1828 novel Pelham he wrote that to look good in black “people must be very distinguished in appearance”. Stylist Alan Flusser says that the dandies of the day took this comment as a challenge and adopted the color to prove themselves worthy.

Formal Myths: Top Hat Origins

Wikipedia points out that the popular story of an English haberdasher named John Hetherington first creating and/or wearing the top hat and causing a riot in the streets of London has no factual basis.

What’s in a Name?: “Fob”

A gentleman’s watch was carried in a hidden pocket called a fob and the name eventually became associated with the decorative chain or ribbon attached to the watch.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie