The time has finally come to say that conventional black tie is dying. There is no longer a uniform described by the phrase.

Russell Smith, Globe & Mail, December 2009

Business Casual: Formality in Decline

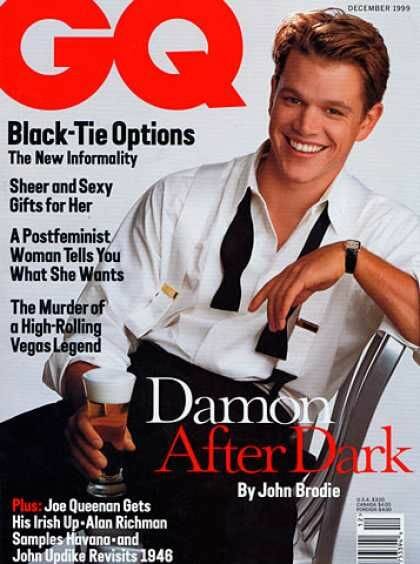

As the nineties progressed, the power suits of the yuppie era morphed into the chinos and running shoes favored by the young, non-conformist vanguard of the dot-com boom. At first, this trend in business attire had little impact on formal wear. “The backlash from casual Fridays turned out to be one of the best things that ever happened to the formalwear business,” reported menswear trade journal Daily News Record in 1998. “It gave baby boomers and Gen Xers the perfect excuse to splurge on drop-dead tuxedos for their weddings, black-tie parties and those very special evenings.” The lead-up to the new millennium only fueled the black-tie fire: in 1999 mainstream tuxedo manufacturers were reporting increased sales orders of up to 100% over the previous year.

- Business Casual: Formality in Decline

- Creative Black Tie: Variations on a Classic Theme

- Red Carpet Black Tie

- Dressing-Down Black Tie

- Formal Minimalism: Back to Basics with Evening Attire

- Millennial Tuxedos

- Under the Jacket: Y2K Shirts, Waist Coverings, and Accessories

- The New Alternative: The Black Suit

- Presidential White Tie

- Millennial Etiquette: Road to Redundancy

- Formal Facts

As with every new generation, the youth of the day were intent on putting their unique stamp on formal wear. They first experimented with bohemian chic then, as hoodies and cargo pants became the new haute couture, the dress-down mindset finally infiltrated dress-up clothing.

Creative Black Tie: Variations on a Classic Theme

Red Carpet Black Tie

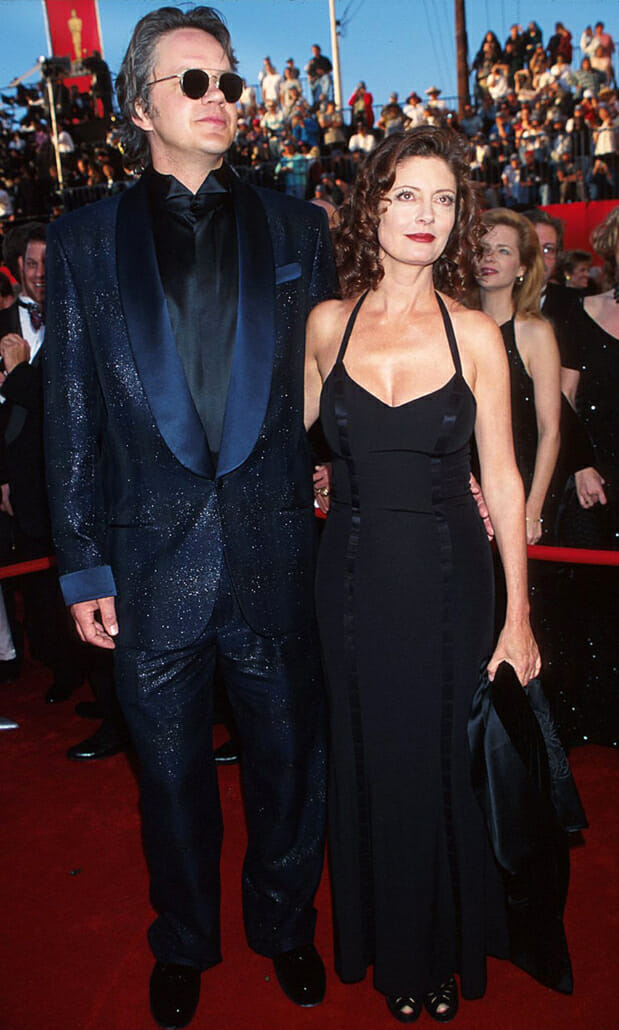

According to the Academy Awards Web site, the term Creative Black Tie came into fashionspeak during the late eighties as the entertainment industry began to redefine party attire with the changing times. The glitterati initially limited their innovations to the tuxedo’s peripherals – a black dress shirt with a black long tie was a favorite look – then by the mid-nineties, the most daring celebs were reinventing the suit itself, sporting Nehru-collar jackets and coats that buttoned down to their knees.

Influenced by popular telecasts of red carpet ceremonies and the antics of maverick celebrities such as Dennis Rodman, American youth opted for increasingly unorthodox styles. “Stop by any high school prom if you want to see outrages (dove gray, fuschia!),” said GQ in December 2002, “and let’s not even talk about the calamities that befall the classic at weddings of the young and feckless.

Too many men in the Age of Whatever, the standard tuxedo, with a hand-tied monochrome bow, still symbolizes stifling formality.”

Dressing-Down Black Tie

Almost as soon as GQ began featuring innovations so beloved by the glitterati, the same magazine also began to deride them. One columnist wrote in 1995 that “the degradation of formal dress runs to the highest income brackets in the land as the confused rich desperately try not to be mistaken for headwaiters. I sympathize, but black shirts, band collars, T-shirts, jeans below dinner jackets, leather ties and what I supposed are homages to [TV cowboy] Bret Maverick are not the answer.” Such sentiments were shared by many fashion writers of the time including the authors of Men’s Wardrobe. They recommended leaving the more extreme red carpet trends to the celebrities in favor of exercising restraint. “At most formal affairs it is preferable to be quietly chic rather than stridently fashionable,” the book counseled. “Never let your clothes speaker louder than you do.”

Instead, style authorities offered a relaxed look epitomized by GQ pictorials such as “Black Tie’s New Informality” (1995) and “The Attire Formerly Known as Formal” (1997). On the surface, these titles were highly reminiscent of the magazine’s sartorial iconoclasm of the sixties. This time around, though, the new trends respected the traditional framework of a two-piece suit and a black-and-white palette. Variety was supplied by incorporating elegant substitutes from a man’s existing wardrobe such as open-collared shirts of black or white, black cashmere turtlenecks or, at the dressiest end of the scale, a black four-in-hand tie. For less casual affairs a velvet smoking jacket or even jeans were often recommended (an increasingly popular alternative for creative types despite the initial resistance).

The three-button jackets favored by young renters occasionally popped up in the pages of GQ in the 1990s but by the early 2000s the periodical was eschewing them for being too business-like.

Formal Minimalism: Back to Basics with Evening Attire

Mainstream black tie in the millennium’s first decade was a pared-down minimalist affair.

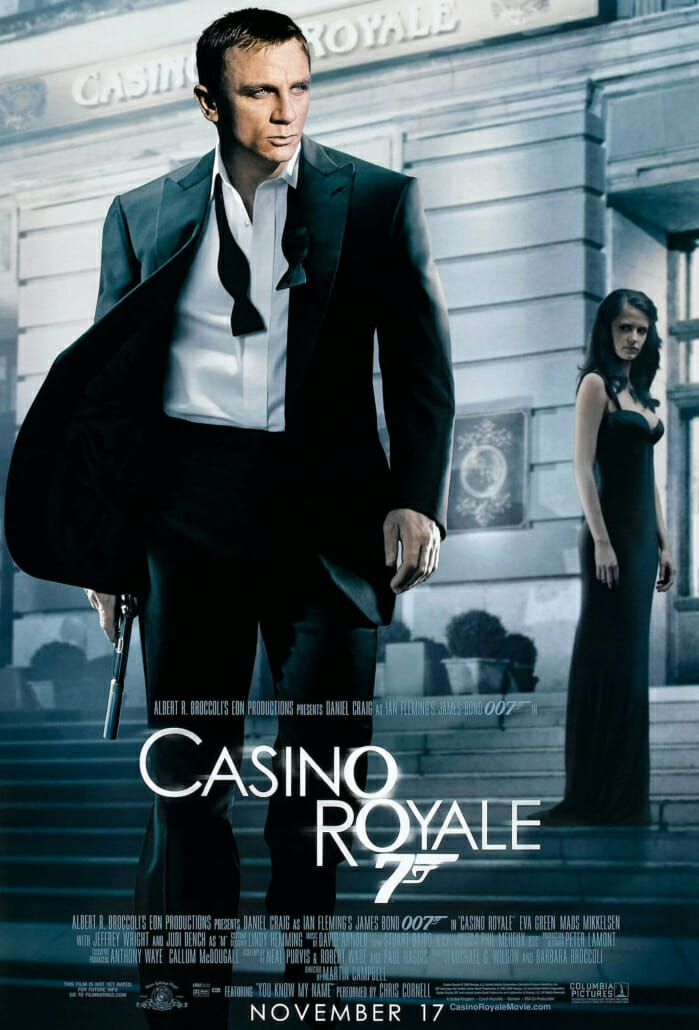

At its most classic it was epitomized by the dashing evening suit featured so prominently in Casino Royale, the hit 2006 James Bond reboot: a traditional peaked-lapel jacket and bow tie updated with a hidden-button shirt and uncovered waistline.

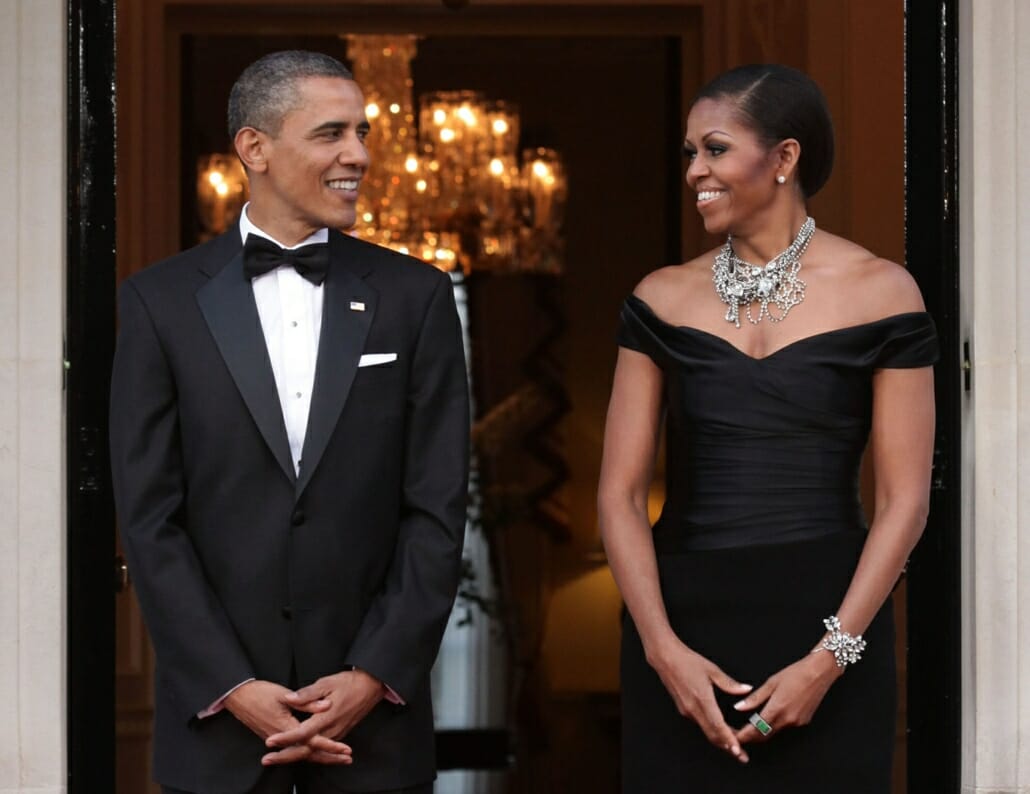

At its most pedantic, it was a glorified black business suit typified by President Barack Obama’s two-button, notched-lapel, single-vented tuxedo that he so frequently paired with a four-in-hand tie.

Millennial Tuxedos

Among men who shared the new Bond’s taste for premium dinner suits, the classic influence remained strong. In 2006 the heads of the Canadian divisions of Oxxford, Hugo Boss and Canali all reported that one-button peak lapels were best sellers, mirroring a return to classic styling in men’s suits in general.

Among the rest of the male population, the trend was more mundane. By the late 1990s one- and two-button notched lapels modeled after common business suits had become the most popular styles of dinner jacket and even designers as conservative as Ralph Lauren were including them in their formal lines.

Whether classic or contemporary, millennial tuxedos remained acceptable in only black or midnight blue. They also shared a distinctly minimalist look that was fashionable in regular suits during this time, manifested in slim-fit tailoring, single-breasted jackets and flat-front trousers that frequently featured side tabs instead of suspenders. Finished satin waistbands were also becoming increasingly popular among men who liked to dispense with conventional waist coverings, an innovation that traditionalists condemned as another casualty of the age of convenience and little more than “a formal version of the Sansabelt”.

Under the Jacket: Y2K Shirts, Waist Coverings, and Accessories

2000s Tuxedo Shirts

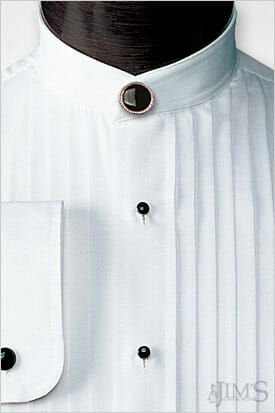

For sophisticated dressers, the turndown collar had vanquished the wing collar by the late 1990s, either in the traditional spread collar fashion or the newer, less formal semi-spread style. Fashion authorities preferred the turndown for its minimalism while etiquette authorities favored it for its appropriateness, citing the classic wing collar’s original role as full-dress attire. For the average American male, though, a flimsy wing collar shirt and polyester pre-tied bow tie remained the standard accompaniment for rented tuxedos.

By the late nineties, some formal shirt manufacturers were including a fourth stud opening to account for the fact that the lower part of the shirt was often worn uncovered. This wasn’t an issue for modernists who preferred the fly-front shirt with its covered buttons and unpleated piqué front. French cuffs remained a must for either style of shirt.

Millennial Waist

During the nineties, the waistcoat surpassed the cummerbund as the preferred method for adding personality to a dinner suit and paisley was the most popular pattern on both, especially for rented formalwear.

In the following decade GQ and Details first cautioned against flamboyant cummerbunds and vests then encouraged readers to “ditch the cummerbund” altogether in order to “achieve a cleaner, more modern look”. In Britain, the fancy waistcoat was a popular fad among the general populace if not among the experts.

By the end of the 2000s several etiquette authorities on both sides of the Atlantic were advising that waistcoats and cummerbunds had become optional. Conversely, traditionalists such as Esquire stuck to their guns and insisted the waist remain covered either with one of the conventional accessories or with a double-breasted jacket.

Millennial Ties, Shoes and Accessories

The formal four-in-hand tie first introduced in the mid-nineties as an alternative option for Creative Black Tie became increasingly popular until GQ announced in 2004 that, like it or not, “it’s here to stay”. The magazine advised that such “straight ties” should match the width and material of lapels and always be black. The bow tie was by no means out of the picture though. GQ continued to give it equal coverage in its pictorials while the more conservative Esquire maintained that it was the only neckwear appropriate for black tie.

Other formal trends favored by modernists were slip-ons instead of pumps, well-polished calfskin shoes instead of patent leather and silk pocket squares instead of linen (although an empty breast pocket was preferred by most minimalists).

The New Alternative: The Black Suit

The tremendous surge in tuxedo rentals just prior to the millennium was accompanied by a similar explosion in rentals of three- and four-button black suits. As the years progressed, these suits were added to more young men’s wardrobes and became as popular in the office as they were in the night club. By 2003 they were a common enough sight at formal events to be included in the etiquette book A Gentleman Gets Dressed Up under the heading “The Other Black Tie”.

It is preferred by younger men likely for economy, style and familiarity. Economy because instead of renting tuxedos each time or buying one that is rarely ever worn, a black suit can be used not only at formal evening functions but also at informal day and evening functions. Style because it mirrors suit styles and is therefore seen as hipper and more modern than the century old tuxedo. Familiarity because they are unfamiliar with details like shawl collars, satin facings, waist coverings, wing collars, bow ties and can feel intimidated by them.

The book explained that the black (or midnight blue) suit should be cut in an understated, classic style and accompanied by a simple white dress shirt with a turndown collar, an elegant tie in a solid color (“a silk crepe in black, dark blue, or silver works well”), freshly polished smooth shoes and dark, un-patterned socks. GQ’s initial forays into the black suit alternative recommended that “you must trick it out” with standard black-tie fixings but they later dropped the faux-formalwear approach, proposing a more business-like look including a black four-in-hand instead of a bow tie.

Presidential White Tie

The venerable full dress rig also suffered its share of ignominy during this dress-down era, primarily thanks to American presidents. During the first decade of the millennium President Clinton, President George W. Bush and future President Obama all appeared in distinctly long-waisted tailcoats which, while not incorrect, were certainly inelegant particularly when considering that all three wore waistcoats that extended even further below. (Bush’s trousers were slung so low they appeared to be weighed down by a holstered six-shooter.) This sartorial solecism was mild compared to Bush’s and Obama’s choice of a black-tie turndown collar and, on one occasion, Obama’s blatant omission of the mandatory white waistcoat. Esteemed purveyor of classic American men’s clothing Ralph Lauren also contributed to white tie’s woes by proffering not one but four styles of notched-lapel tailcoats in the 2000s.

Fortunately these formal transgressions were largely limited to the former colonies as European heads of state ensured that the Old World maintained a firm grasp on the subtleties of full-dress elegance.

Millennial Etiquette: Road to Redundancy

Two Views of Classic

While the creative black tie trend of the nineties faded into history just like the peacock fad of the sixties and seventies, the dress-down movement was more similar to the casual innovations of the thirties in that they became an accepted part of the formalwear canon. However, there were notable differences between the latter two trends. The garments introduced in the golden age were all unique to formal wear and were limited to less formal summer affairs. The notched lapels, uncovered waist and long ties of the millennium, on the other hand, were drawn from business attire and their formality was a matter of debate. Traditionalists who defined formal wear as clothing that maintained convention and upheld the highest standards naturally viewed the trends as an erosion of formality. Conversely, modernists who interpreted formal wear simply as conservative clothing viewed the changes as an update of formality, not a downgrade of it.

The modernist camp was championed by GQ which repeatedly described tuxedos with notch lapels, center vents and flap pockets as “timeless” and “classic”. This fallacy perpetuated the impression among inexperienced formal dressers that the tuxedo was essentially just a black suit with shiny lapels; for young men more concerned with familiarity than formality modernists assured them they were one in the same.

Diluted Dress Codes

The Black Tie Optional code which had previously received little attention from etiquette authorities became a going concern in the mid nineties as it appeared on an increasing number of invitations. The expert advice offered to guests ran the gamut from always wearing a tuxedo to never wearing one. The only consensus was that considerate hosts should avoid the term at all costs precisely to prevent such confusion.

Adding to formalwear uncertainty during this time was the appearance of the even more ambiguous Creative Black Tie code. Authorities generally defined this as the replacement of a standard black-tie article with a more casual or whimsical equivalent. Examples ranged from prom-night tacky (colored and patterned waist coverings and/or bow tie) to L.A. chic (black long ties or black open-collared shirts) to thematic twists (cowboy boots and bolos for a western night or red and green accessories for a Christmas party).

Muddying the waters even further was the period tendency for men to show up at traditional Black Tie events dressed in a common black suit. In the mind of Canadian style columnist Russell Smith, this development had rendered the dress code virtually redundant:

The time has finally come to say that conventional black tie is dying. There is no longer a uniform described by the phrase: So many variations on the dinner jacket have become popular that the whole point of the outfit – uniformity – is lost. If black tie means a black suit and a regular black long necktie, then the distinction between it and the business suit is erased, and there is no longer any reason to insist on any particular form of dress. As a result, inevitably, there will be fewer and fewer parties that demand the conventional costume.

Declining Tradition

By the 1997 edition of the Emily Post series, society balls were the only occasions that still required tuxedos simply by implication. All other formal affairs required black tie only if specifically stated on the invitation and such invitations were increasingly rare in the new millennium. In 2001 the tragic events of 9/11 severely dampened America’s desire for elaborate celebrations. Then in 2008 the “Great Recession” drastically curtailed spending on weddings and proms. As a result, several formalwear retailers closed their doors while their suppliers also went bankrupt or merged with longtime competitors to stay solvent.

Even when invitations did call for black or white tie a growing number of people chose to ignore the dress code. Most famously, British MP Gordon Brown arrived at his first Mansion House white-tie dinner as Chancellor in 1997 wearing a suit and refused to dress properly right up to the 2007 dinner, just seven days before he took the reins as Prime Minister. That same year The National Post reported that in Toronto

The notion of dressing for an occasion is one people are choosing to ignore more and more . . . Many events are explicit, black tie and long dress, and still attendees don’t clue in. Some guys, especially younger fellows who feel they’re really successful, take pride in flouting dress codes and showing up in business suits, often not dark, and without a tie.

On the brighter side, although President George W. Bush’s distaste for formality put an end to the traditional White House reception for the diplomatic corps – one of the last remaining full-dress affairs in Washington – the First Lady managed to convince her husband to honor Queen Elizabeth II with a white-tie state dinner in 2007. Similarly, Gordon Brown finally overcame his insolence a few months after becoming Prime Minister and purchased a $3,000 Savile Row dress suit (tailcoat) which he first wore to a state dinner at Buckingham Palace.

Formal Facts

The Band Collar Shirt

The band collar shirt with button cover was a popular alternative at show business ceremonies in the early’90s. However, by 1995GQ‘s style arbiters were proclaiming that the band was now banned.

The New Formal

The dress-down black-tie look (and topic) was a favorite of GQ in the ’90s. Later there was a noticeable shift to the black suit as the ultimate symbol of elegance not only in GQ pictorials, but also in ads for premium goods which would have typically featured tuxedo-clad models in the past.

Jacket. Dinner Jacket.

Casino Royale, the hugely successful 2006 “reboot” of the James Bond franchise not only breathed new life into the fictional spy but also into his formal wardrobe. Brioni’s millennial take on the classic dinner suit appealed to legions of young 007 wannabes previously unfamiliar with traditional black tie.

The Millennial Waist

Satin-finished waistbands became popular as less men opted for waistcoats or cummerbunds. Flat-fronts were another common feature on millennial formal trousers for lower end tuxedos.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie