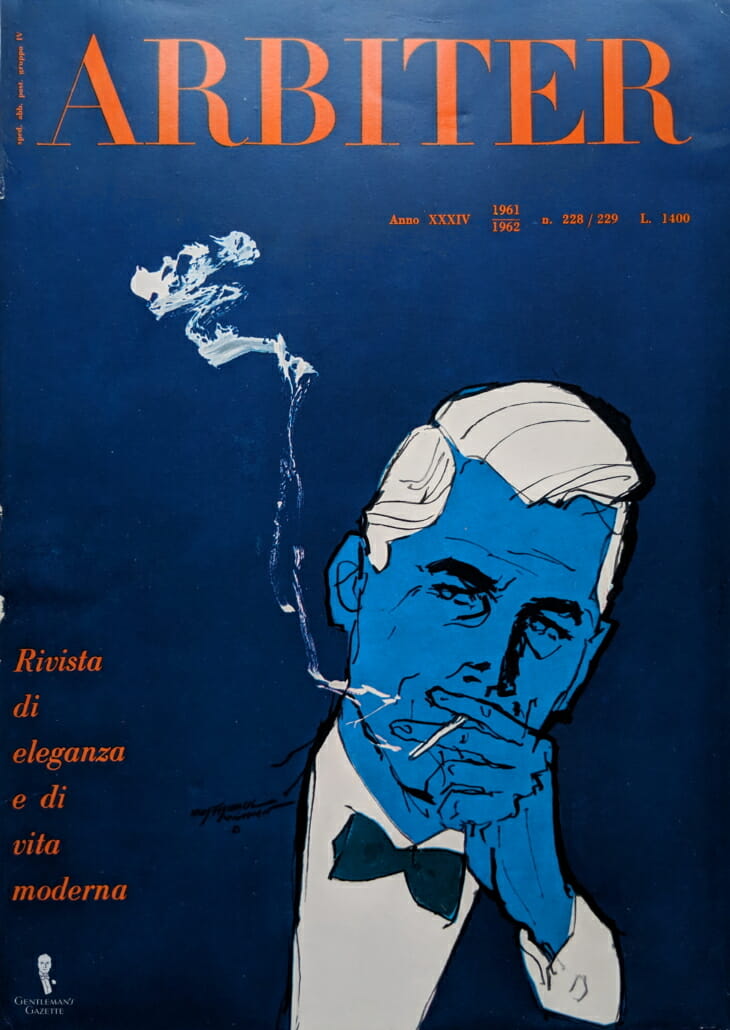

- Mid-Century Modern

- Continental Dinner Suits: Modernity & Evening Wear

- Modern Covers for Modern Waists: Waistcoats, Cummerbunds, and Cummervests

- Fancy Shirts

- Mid-Century Neckwear

- White Tie Deluxe

- Supersonic Separates: Odd Pairings & Broken-Up Ensembles in the Jet Age

- Jet Age Etiquette

- The Times They are a-Changin’: Unconventional Evening Wear

- Style Icons

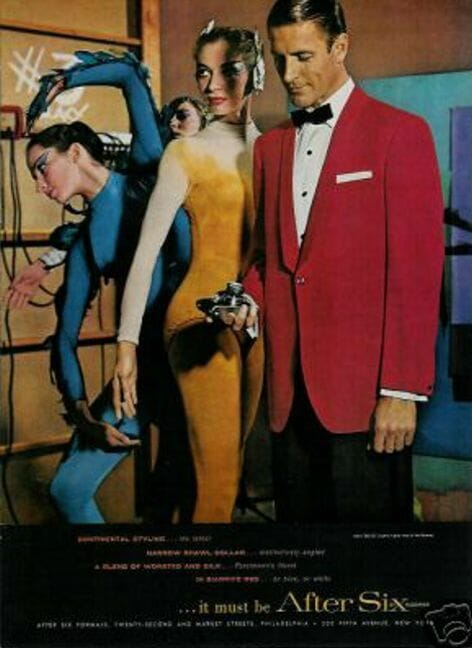

Male formal plumage turns to iridescent splendor!

After Six tuxedo ad, 1955

Mid-Century Modern

The highly popular 1955 novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit utilized the middle-class American male’s typical corporate attire to represent the conformism of the early fifties. Yet by the time of publication, these men were feeling the influence of rock ‘n’ roll’s youthful rebelliousness and were seeking a wardrobe that better reflected the modern world in which they were living. The advent of jet travel and space flight provided the perfect inspiration and so streamlined styles and synthetic materials became popular in men’s attire just as they had in their automobiles and household appliances.

Continental Dinner Suits: Modernity & Evening Wear

The Continental Look

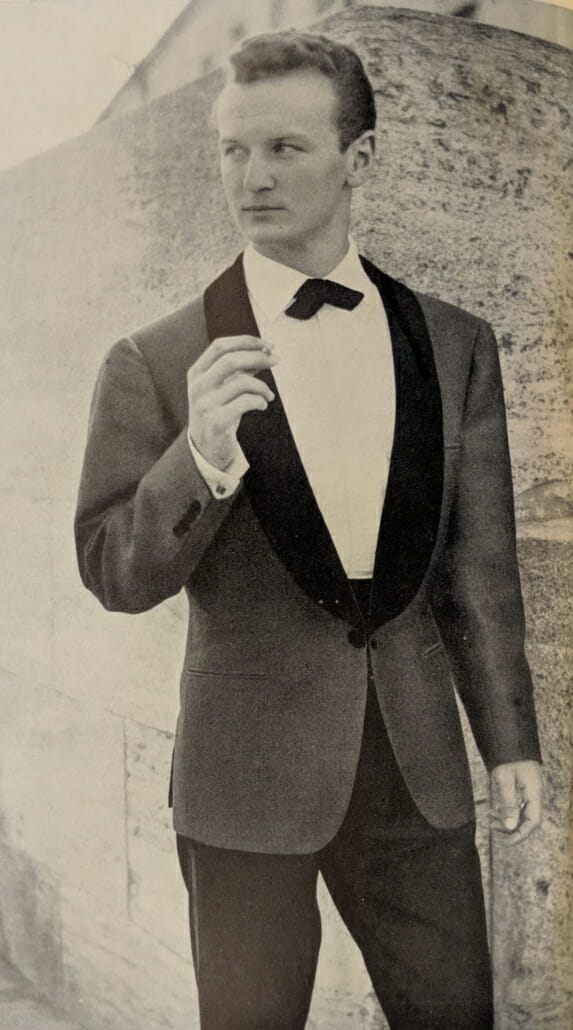

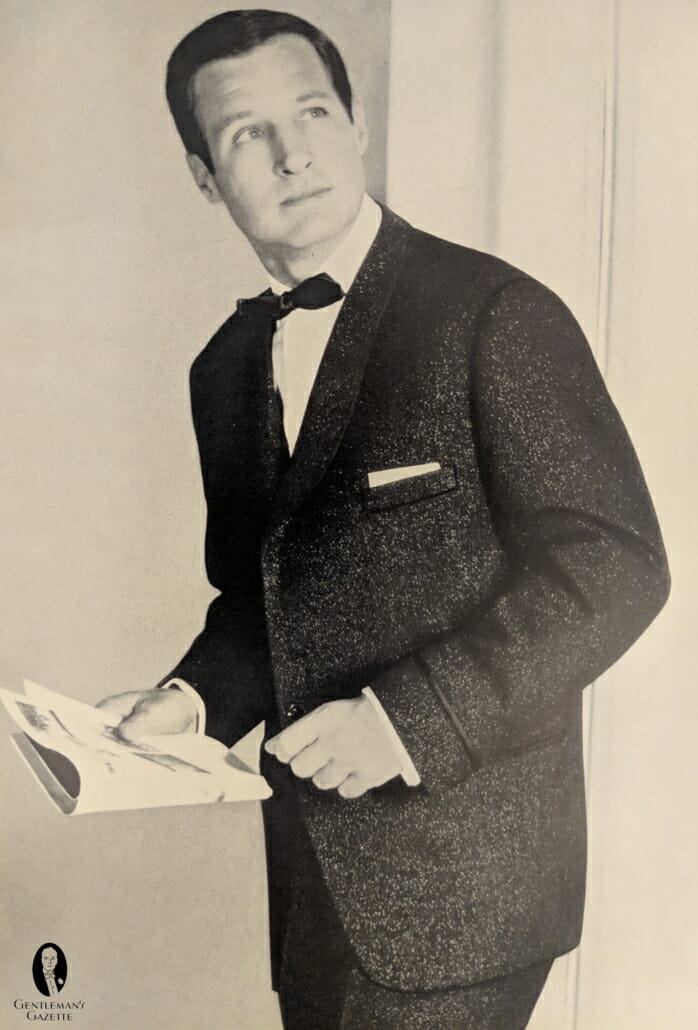

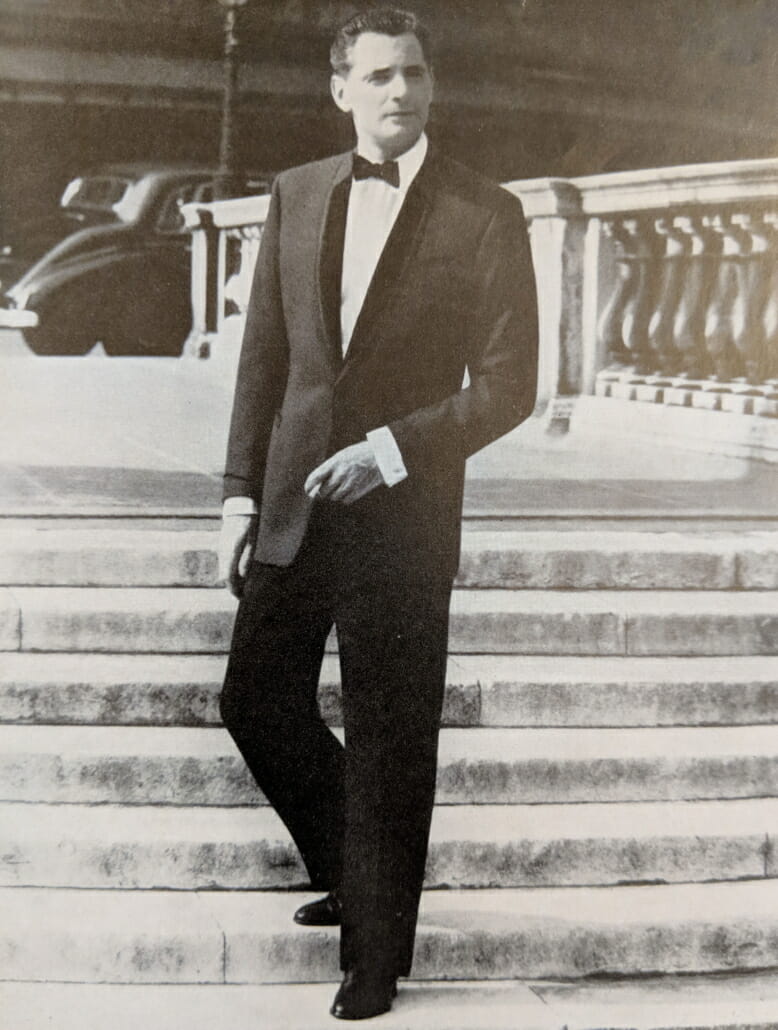

The modern face of the suit for Americans and Britons alike was the slim Continental look that emerged from Italy in the late fifties. This new style featured jackets that were shorter and more fitted than traditional cuts and trousers that were narrow and cuffless. It became the basis of the English Mod fashions of the early sixties and when combined with a concurrent return to elegance in men’s attire it resulted in a deluxe makeover of the dinner suit.

The continental-style dinner jacket was typically single-breasted and had narrow lapels. The Roman influence led to the replacement of the popular but casual shawl collar with dressier choices such as the recently-returned peak lapel, the notched lapel newly imported from business suits and the notched shawl collar in various shapes such as the “cloverleaf”. Lapel facings became more elaborate over the years, beginning with simple silk or braided piping in the late fifties and progressing to embroidered, brocaded or jacquarded motifs on a satin base. The same embellishments were also applied to turned-back sleeve cuffs, pocket edgings, and trouser stripes. The most fitting choice of suit fabric for this continental elegance was silken black mohair.

Modern Covers for Modern Waists: Waistcoats, Cummerbunds, and Cummervests

Underneath the dinner jacket often lay the newly reincarnated waistcoat, now commonly referred to as a vest in America. When purchased as part of a three-piece suit, the waistcoat was usually decorated with the jacket’s trimming before its reverse began to disappear in the mid-sixties.

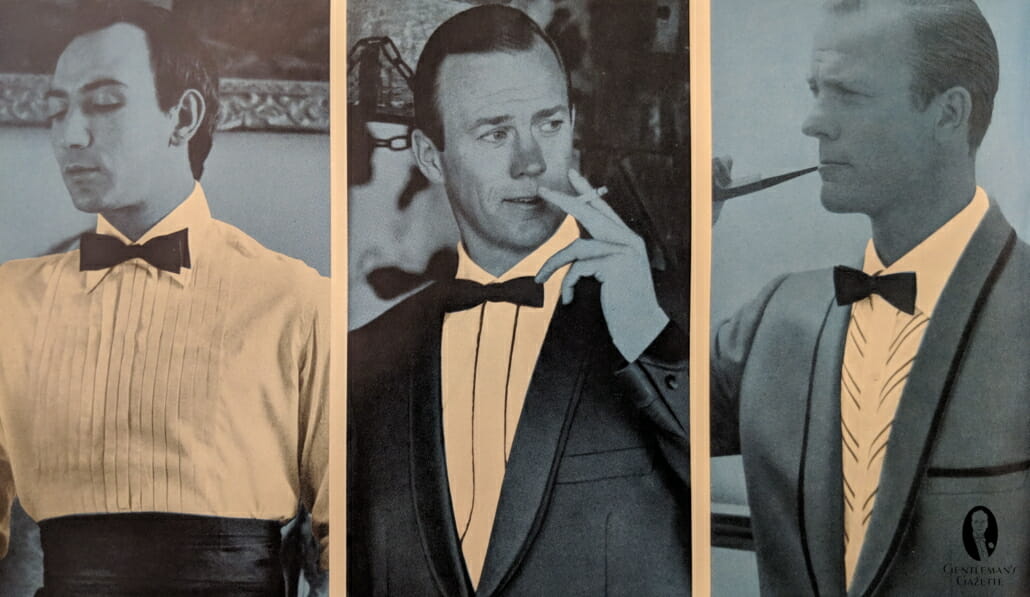

A less formal alternative was the cummerbund which had finally been accepted by etiquette authorities for year-round use. Although fashion magazines occasionally featured waist coverings (and matching bow ties) in various patterns and colors, conduct manuals mandated that only black or midnight blue be worn with the dinner suit.

Fancy Shirts

Paralleling the increasingly ornate jackets and waistcoats, the stylish formal shirt of the time began displaying columns of understated ruffles or subtly embroidered lace either along the placket or across the entire front of the shirt. After the new style appeared on fashion-forward celebrities at the 1959 Academy Awards the patterns and effects became increasingly elaborate. Other options for shirt bosoms included an ever wider variety of pleats and tucks, frequently with fly fronts that did not require any studs.

Mid-Century Neckwear

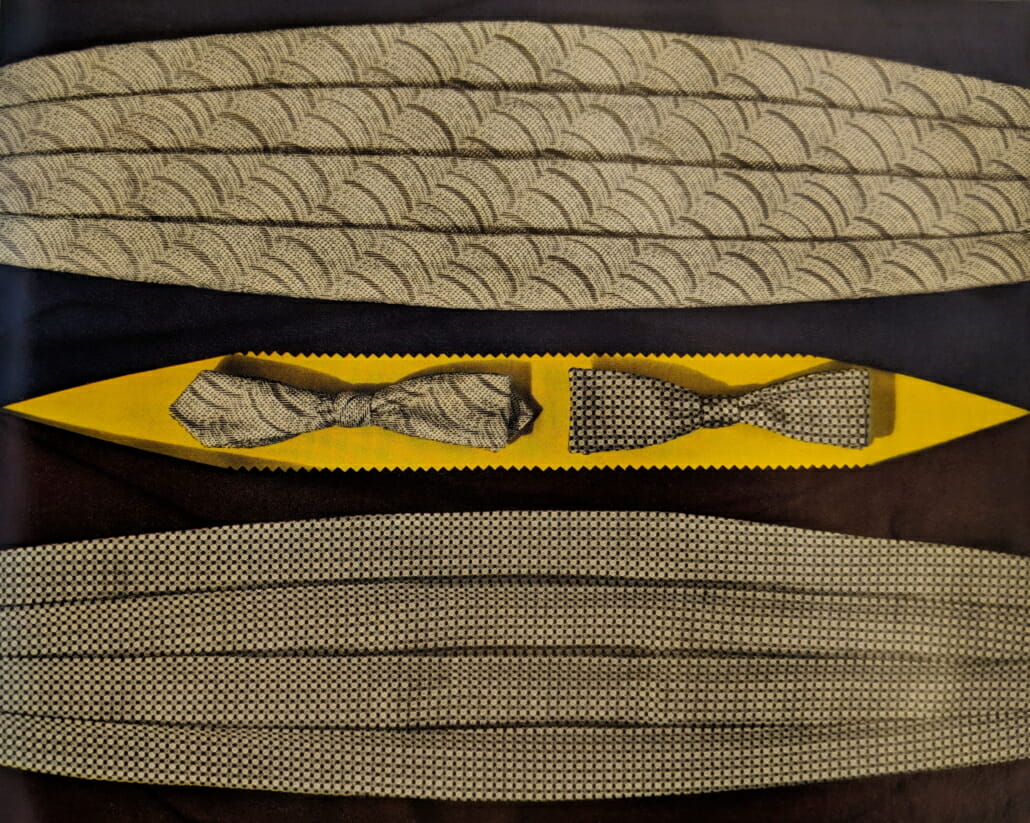

Also resurrected from black-tie limbo in the late fifties was the elegant butterfly bow tie which had formerly been eclipsed by the straight-end batwing style. Trendsetters experimented with tucking their bow ties under their collar points or replacing them altogether with the newly invented continental tie.

White Tie Deluxe

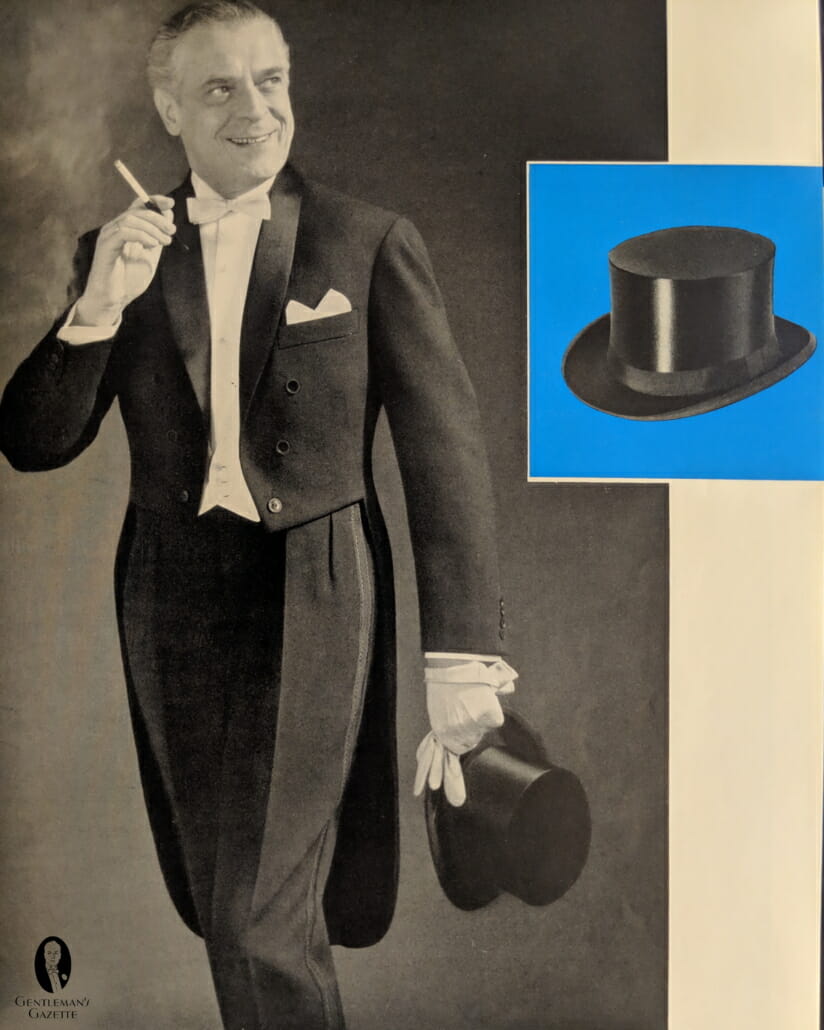

Menswear magazines periodically presented their take on the continental white tie, depicting flourishes such as shantung silk tailcoats, velvet collars and cuffs, crimson- lined capes and even a pale blue jacquard silk waistcoat and tie. However, these styles were completely at odds with the highly traditional nature of white tie and it is unlikely they were ever adopted by anyone outside of the fashion industry.

The only white-tie novelty of the period that would have any staying power was much less conspicuous: In December 1963, Esquire introduced a starched bosom white piquédress shirt that was unique for having the wing collar attached to the shirt.

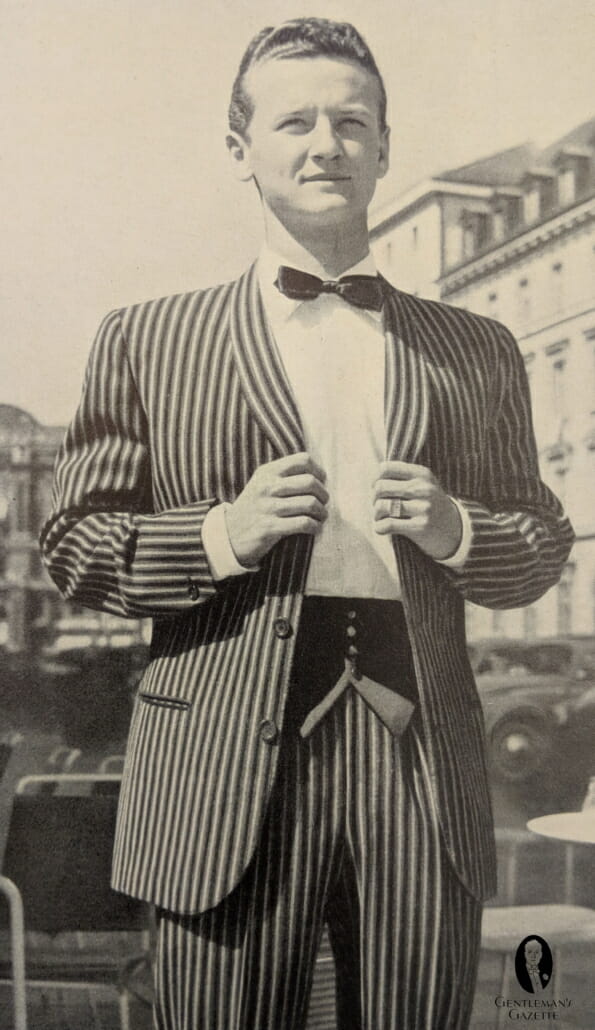

Supersonic Separates: Odd Pairings & Broken-Up Ensembles in the Jet Age

Informal Jackets

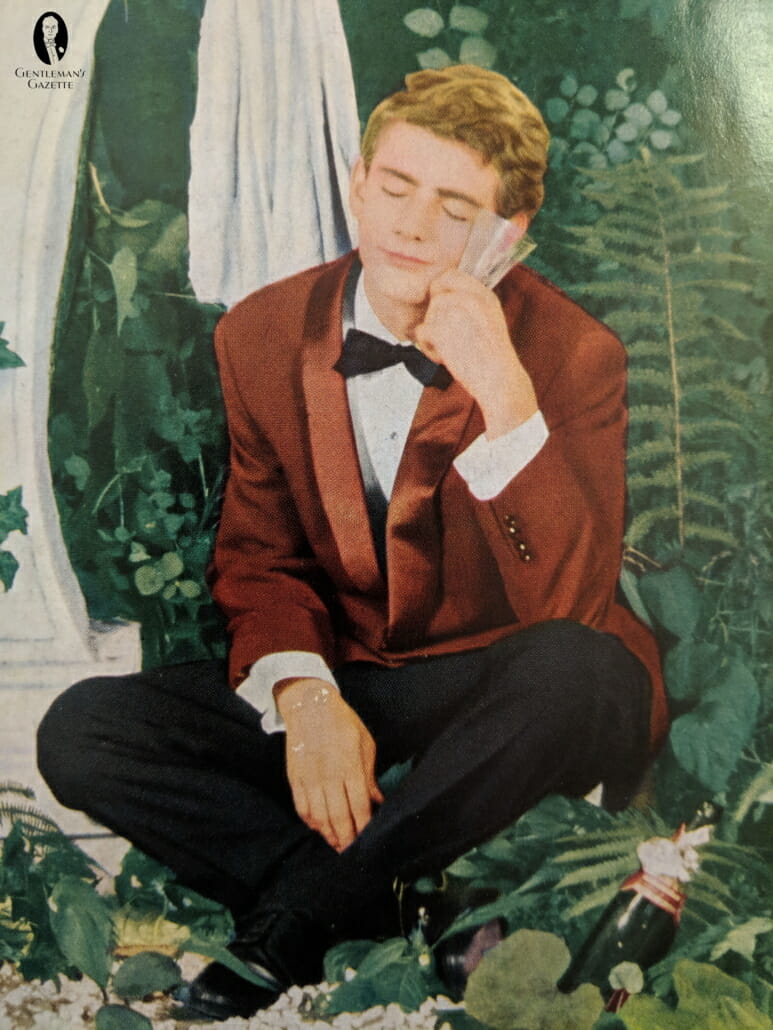

The jet age developments in odd (non-matching) dinner jackets were not nearly so subtle as changes to the classic suit. In the early fifties, formal wear retailers had begun to offer warm-weather coats in blue and maroon but these were relatively conservative hues and rarely seen. In the somewhat relaxed political climate in the mid-1950s, this trend took off, launching around the time of a 1954 Esquire pictorial that featured a tropical cruiser decked out like a Las Vegas lounge singer. The accompanying description read like sartorial poetry:

The [dinner jacket’s] shimmering sheen of imported sheer silk shantung glistens like a reflection of a golden sun shot with sparking undertones of blue water. Silk shantung slacks pick up the jacket’s blue. A black-ground silk cummerbund and tie, allied to the trousers’ black side stripes, add to smooth sailing with a gold-and-silver Chinese dragon design.

The following year the trend picked up speed with the introduction of “parfait colors”. The February issue of Esquire depicted jacket hues with soda fountain names such as “crushed strawberry” and “French vanilla” which a man could choose for his Caribbean sailing safe in the knowledge that “no one will mistake him for the steward or an errant bartender”. In 1956 iridescent “peacock tones” further fueled the fad thanks to the availability of metallic threads then a couple of years later patterned fabric began to appear, running the gamut from plaid to batik. The only consistent factor in this striking progression was that the jacket was invariably single-breasted and featured a shawl collar that was either black or self-faced.

Keeping pace with evening wear’s new looks were contemporary fabrics equally suitable for the new age. Wool and rayon blends that had originated in the late 1940s became increasingly popular in tuxedos during this time thanks to the synthetic material’s lighter weight, better crease resistance and easier care. Suitings with irregular and nubby finishes also became more common as the fifties progressed

By the time seersucker appeared in dinner jackets in the early sixties, loud colors and attention-grabbing patterns had virtually replaced the classic white summer coat on the pages of menswear magazines. And although the periodicals continued to pay lip service to the stricture that limited these showy alternatives to warm-weather occasions, their depiction in Manhattan theater lobbies and “discotheques” in mid- winter photo shoots belied a broader usage. As if to sidestep this breach of etiquette, editors began to imply that such unorthodox jackets could correctly be worn at one’s own home as a “host coat”.

Tie and Cummerbund Sets

Another vogue of the mid fifties was matching colored and patterned bow ties with cummerbunds of various new styles, most notably the hybrid cummervest. This trend was primarily limited to warm-weather black tie and began to die out with the introduction of the dressier Continental look.

Jet Age Etiquette

Attire

As trendy as they might be, the unconventional jackets and shirts of the period were the exception rather than the rule and standard black tie remained relatively conservative. In fact, in New York as well as in Europe, tropical-weight black tuxedos were preferable for all formal evening occasions, even in summer. The 1963 edition of Amy Vanderbilt’s The Complete Book of Etiquette begrudgingly allowed for colored or patterned dinner jackets but limited their appropriateness to cruises and suggested they were best left to the young. The 1965 edition of Emily Post’s benchmark book had been completely revised for a new generation by her granddaughter Elizabeth but its evening wear protocol, while significantly condensed, offered equally limited concessions. Patterned jackets or cummerbunds were acceptable but only in summer and only for “less formal” parties. The younger Post did support the new trend for matching bowties with colored cummerbunds while Ms. Vanderbilt remained insistent that maroon was the only alternate hue for warm-weather neckwear.

Occasion

The 1965 Emily Post book no longer attempted to list specific occasions when black tie was required, offering instead the umbrella provision that “it’s correct on almost every formal occasion”. Such occasions continued to include the opera (particularly in the boxes and orchestra seats) and opening night at the theater. Movie premieres also called for tuxedos according to an article that same year in GQ (the recently launched successor to Apparel Arts) although “many appear, incorrectly, in dark suits (including those who wear a bow tie in the hope of looking evening-suited in a shadowy lobby).”

The Tuxedo Rules Weddings

A significant new addition to the list was the evening wedding. Previously only the tailcoat or dark suit had been considered appropriate for church ceremonies because the tuxedo was seen as “frivolous”. Now dinner jackets were acceptable in church at even the most formal of weddings. The only caveat was that the coats be strictly limited to black or white according to the season, regardless of whether they appeared on groomsmen or guests. In reality, this development meant little to the average person as wedding parties had been ignoring the prohibition for years. It was also a common practice by this time for Americans to don evening wear for daytime ceremonies, being either oblivious or indifferent to the inherent incongruity.

Renting A Tux vs Owning A Tuxedo

One other contemporary concession made by both Post and Vanderbilt was to acknowledge the practice of renting one’s formal wear instead of owning it. However, this allowance applied only to near-obsolete full evening dress and formal day wear. Tuxedos still were expected to be a pertinent part of a man’s wardrobe “if he is going to have an active social life in sophisticated circles.” Ms. Vanderbilt also revised her advice on correspondence etiquette to indicate that “black tie” should be specified on dinner invitations rather than expecting guests to infer this based on the formality of the request as was previously the custom.

In the United Kingdom, dinner jackets continued to be the norm for social gatherings according to Etiquette Handbook published in 1962. Author Barbara Cartland advised that if the Black Tie dress code did not appear on an invitations for “ordinary dinner parties and for informal dances” then full dress was expected. No doubt this applied to the social circles where it was “perfectly normal for people to eat at 9 p.m. and to regard the night as young at midnight.”

Full evening dress was also worn to film premieres attended by royalty if a person was likely to be presented to them. Conversely, the 1964 book ABC of Men’s Fashion noted that “Royalty has now indicated to ball hostesses on many occasions that . . . full evening dress need not be worn. This has really meant the death knell to white ties and tails that were already ailing.” In America, white tie remained reserved primarily for opera openings, as well as balls, dinners (especially public dinners) and weddings of the most formal nature.

The Times They are a-Changin’: Unconventional Evening Wear

The highly unconventional dinner jackets of this period were representative of a much larger social upheaval taking place in the sixties. America’s conception of “formal” would become ever more subjective in the years ahead as the first postwar generation rebelled against their parents’ conservative values. In the process, time-honored black-tie convention would be brought to the verge of extinction.

Style Icons

Tuxedo Icons: Modern Playboys

When Playboy magazine created its iconic logo in 1953 it chose a rabbit to represent friskiness and a formal bow tie to signify masculine elegance and sophistication.

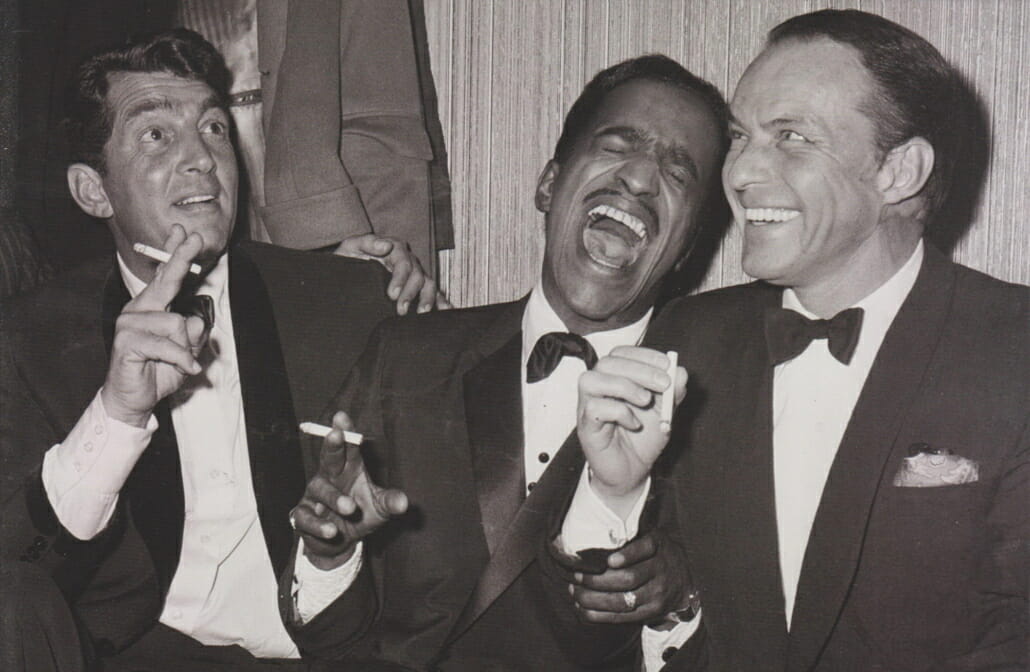

The epitome of the tuxedo-clad playboy image were performers Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Frank Sinatra, Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop, collectively known as “the rat pack. These friends would often join each other on stage in the early ’60s for some of the most legendary shows in Las Vegas history. Sinatra once said, “For me, a tuxedo is a way of life.”

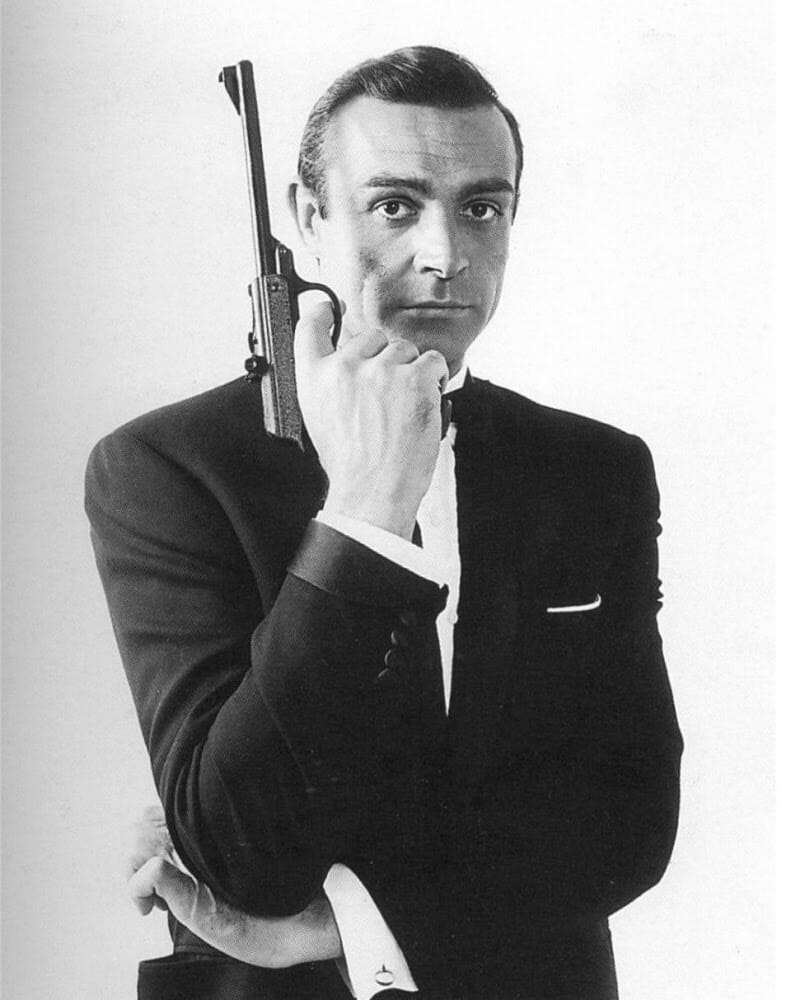

The fictional embodiment of the dashing bon vivant with a penchant for stiff drinks, pretty women and fast cars was the James Bond character first made famous by Sean Connery in the 1962 film Dr. No.

The Jet Age

The first non-stop transatlantic flights of the late 1950s spelled the end of the ocean liner’s heyday. But the new passenger jets also made pleasure cruising more accessible for many Americans, opening a new chapter in shipboard black tie.

Tuxedo Rental Boom

The tuxedo business was largely a retail business up until the 1960s, selling traditional black formal suits that lasted a lifetime. The advent of color helped make formal wear an ever-changing fashion statement and the rental business subsequently exploded in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s.

Explore this chapter: 3 Black Tie & Tuxedo History

- 3.1 Regency Origins of Black Tie – 1800s

- 3.2 Regency Evolution (1800 – ’30s) – Colorful Tailcoat & Cravat

- 3.3 Early Victorian Men’s Clothing: Black Dominates 1840s – 1880s

- 3.4 Late Victorian Dinner Jacket Debut – 1880s

- 3.5 Full & Informal Evening Dress 1890s

- 3.6 Edwardian Tuxedos & Black Tie – 1900s – 1910s

- 3.7 Jazz Age Tuxedo -1920s

- 3.8 Depression Era Black Tie – 1930s Golden Age of Tuxedos

- 3.9 Postwar Tuxedos & Black Tie – Late 1940s – Early 1950s

- 3.10 Jet Age Tuxedos – Late 1950s – 1960s

- 3.11 Counterculture Black Tie Tuxedo 1960s – 1970s

- 3.12 Tuxedo Rebirth – The Yuppie Years – 1970s

- 3.13 Tuxedo Redux – The 1980s & 1990s

- 3.14 Millennial Era Black Tie – 1990s – 2000s

- 3.15 Tuxedos in 2010s

- 3.16 Future of Tuxedos & Black Tie